That disgusts me.

George Tannenbaum on the future of advertising, the decline of the English Language and other frivolities. 100% jargon free. A Business Insider "Most Influential" blog.

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

Trigger Warning.

That disgusts me.

Monday, February 27, 2023

Time, Tide and Advertising.

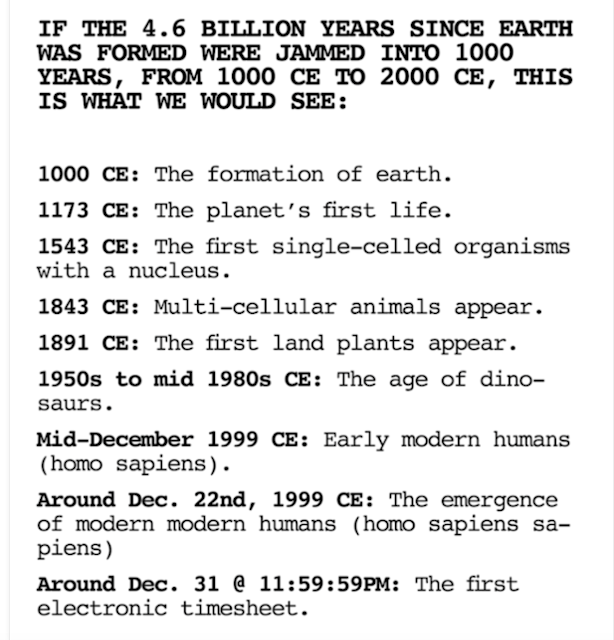

I believe that the same elements that made Homer's Iliad and Odyssey listen-to-able 6000 years ago, are the same elements that make movies watchable, books readable and tv-shows bingeable today. As Pulitzer-winning historian Barbara Tuchman once said, "the persistence of normal is strong." Group 2-ers claim Bernbach as a founding member. He said, "advertising should be based on ‘simple, timeless, human truths.’”

Or are we doing work for the next quarter of a century?"

Friday, February 24, 2023

Not short. Not funny. But here.

If you write a blog as assiduously as I do (contrary to popular belief, assiduously does not mean I type it with my ass) you learn a lot about media. And life.

In fact, if I ever were in the position to hire people again, I'm not sure I'd ever bring someone in who wasn't daily involved in some sort of craft. Doing something daily forces you to see things you don't see if you're less regular about doing them.

For instance, I have always--even when living in the city, spent about 100 days a year walking by the sea. Some of that was while I was on vacation--usually somewhere warm and azure. Some was driving up to a dog-friendly beach and playing fetch in the water of the turbid Long Island Sound with Whiskey. Most was walking along the path of New York's East River. (Though we call it a river, it's not. It's a tidal estuary--and if there's any water in the East River at all, the PCBs and other carcinogens are probably salty.)

Despite my regular maritime proclivities, the sea becomes 'living,' when you live on it and see it every day. You see things you don't see even when you're merely a regular visitor. You see the change of seasons, the changing character of waves, the Rothko-like blurring of the horizon, the sky and the brine. You see and hear the life of the littoral; clams washed onto the street by an over-achieving wave, or dropped there by a gull. You see the lacerated carcass of fish that have escaped the razor talons of an osprey. You see diving ducks and geese taking off just barely like Howard Hughes' failed behemoth, the Spruce Goose.

You see the phone poles that are home to almost-round gulls who feast on the trillions of migrating bunkers our species hasn't yet destroyed. You see hopeful fishers neck deep in the murk trying for stripers or blues early and late in the season. You see buttermilk skies, god rays and rainbows. You see squalls and storms and hear thunder and see lightning. You hear the laughter of children with buckets and throwing sand at their little sisters, their mothers tsking and perhaps dreaming of a Xanax.

The same happens, I think, when you write and publish every day. First you become attuned to your surroundings. You turn yourself into a super-human of sorts, an all-observing story machine.

Your memory is trained to remember a funny t-shirt you've seen, or a snatch of dialogue overheard. You hear sounds that are otherwise drowned out by their older-brother-sounds, the type that usually demand more attention.

Your brain becomes a giant stewpot in an army mess hall feeding ten-thousand troops a day. You throw everything into the pot hoping for a dance of flavors. Hoping that when you ladle the slop out on a thousand tin trays, something will be enjoyed and something will be gained.

You also learn the patterns of your readers and as important, the lack of patterns.

Often I write something. I'll say to myself, for whatever reason, 'this is really going to take off.' And I get the Bronx-born equivalent of that old Zen Koan--nothing but the sound of one-hand clapping. Other days I'll say, 'well that was kind of lame-brained,' and the post will take off.

I learned from that that it makes no sense to try to make sense out of things. Whether you're a human-brain or a high-performing computer, in so many things there are too many uncontrolled and uncontrollable variables to be able to count on anything, especially counting.

Anyone who tells you, 'don't do x because of y,' has essentially given up. You can always do something to x that changes y, but you usually don't know what where or when.

That's really it for today.

I've found through the years that Fridays are slow days in the blogosphere. I try to counteract low volume usually by writing something funny and short.

Today's post is neither.

But who knows.

It might still go over well.

Thursday, February 23, 2023

Jabber.

If you are attuned to listening, you hear a lot of words you wish you hadn't.

Words that hurt your ears. Words that have no meaning. Words that muddy, rather than clarify.

You hear them all the time. They're usually mean and shrill and demeaning. They usually shout at you without kindness or consideration.

Worse are those who try to bamboozle you, or bullshit you with big words or jargon that really don't have any meaning. This is another technique designed to bring you down a peg. It's a way of saying, 'you don't understand our specialized language. Therefore you're not smart, cool or one of us.'

Cliques in high school do this sort of thing. The 'in' crowd has their own language, specifically designed to keep others out.

Agency life was full of this linguistic bombast, segregation and ostracizing. Without mangling and Newspeak, agencies would be as quiet as a tomb. I heard it a lot when someone was trying to kill an idea or to get you to do something their way. They'd trot out, or shovel out the crap. If you weren't savvy enough to catch on, you often wound up wounded. Or plowed under by an empty and hurtful loquaciousness.

For about the last 102 years of my life, I've tried to write in simple English so my readers could understand it. Especially when I write in service of a client.

There are so many meaningless words we expect to read in certain situations because everyone uses them. If you're bold enough to try to get someone to clarify them, you get a lot of stammering as a response. If someone does try to explain, chances are they'll explain things using the exact same words that needed explaining in the first place.

"Agile means we'll move with agility using an agile methodology."

Not too many hours ago, a friend sent me some gibberish put out by a client I spent a long time working for. This client has a market cap of almost $120 billion. I didn't want to single any one client out, so I did a tiny bit of searching. Things didn't get any better the more I searched.

You can take it or leave it, as you wish.

Some thoughts on writing from George

Orwell's

"Politics and the English Language."

To guide writers into writing clearly and truthfully, Orwell proposed the following six rules:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Along the way, I've added this to it:

There's nothing you can learn about writing--from anyone or from anywhere--that is as important as asking yourself a simple question or five.

Ask yourself these questions as you pick up your pencil or tap on your keys. They can't hurt. And they might help.

1.

Are you writing to impart useful information to people or are you writing to show how smart you are?

A lot of writing I see uses big words and ridiculously long sentences. It doesn't explain anything.

2.

Are you writing to clarify things or to confuse issues? Are you writing to simplify or complicate?

So much of what we read uses jargon and cliches. It's obvious to me that not even the writer knows what they're trying to communicate. Or they're being purposefully deceptive for nefarious purposes.

3.

Are you writing lies or have you decided to tell the truth? That is are you writing honestly, or dishonestly?

I often bump into writing that is as circuitous as the roads in a gated community. If you respect the reader, you get to the point. Don't lead them into cul-de-sacs or dead ends.

4. Are you trying to reach people or bully them?

About 85% of the VOs I hear on television is an announcer yelling at viewers. Much of writing also feels more like berating. Is someone channeling my mother?

5. Do you want people to read what you've written or just see that you have written?

A lot of writing starts out with cliches and buzzwords and stock-phrases that indicate to the reader that the writer has put no thought and even less-candor into what they've sent out. This is writing that allows Authority to say they've done the right thing while doing the wrong thing.

I suppose you can reduce all these questions to one:

Will the reader trust (and like) the writer--even if they're told something harsh--or will they feel after reading that they've been hosed-down with bullshit and the smell is lingering?

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

A New Idea: Humachine.™

If you were born a middle child, as I was, and a child of two perpetually-warring parents, you might have, like me, often assumed the role of conciliator and peace-maker.

In other words, you work to help resolve conflict, to make combatants meet in the middle.

What's more, if you were born with what today is called an eidetic memory, you can recall with some acuity something you read early one morning before the rest of the office was in, and then only for four minutes.

These are two sides to me--two sides that people who know me see, but very few others do.

All that is to say, that back in 1984, I read an op-ed in the New York Times by columnist Flora Lewis, that I think we would do well to re-read today. You can, and should, read the article here. But since you probably won't, because invariably you've got better things to do than to read a 39-year-old op-ed recommended by a slightly daft aged copywriter--let me paste the "SmartPart™" here, complete with George-Selected highlights in yellow.

Lewis writes:

"What I call the Tiffany model, conceived when waste of resources was the major concern, offers a way of reconciling both the need to conserve materials (which will return with recovery) and the need to provide humane work. The key is quality.

"Real quality requires craftsmanship, hand-finishing. Historically, it was reserved for the rich. The second industrial revolution can be used to provide it for everybody, just as the first made possible mass production and distribution. That was achieved by an economic model based on great quantities of cheap goods. Henry Ford's assembly line made the automobile everyman's transport. The robot can now replace low-skilled workers. The next step is the equivalent of a Rolls-Royce for everyman, by bringing back the artisanship of finish that makes the big difference. Of course, the price would be much higher. Consumer credit offers a solution. If a car were so well made that it only began to wear out in 20 years, would people mind taking 10 years to pay it off? Would they really prefer plastic plates to good china, plywood to fine furniture, if the cost in terms of yearly outlay were about the same? Making good goods that last would leave the base work to machines, save material and employ more people in the rewarding task of adding quality by individual taste and skill. The popularity of do-it-yourself reflects humane values to be won. This would mean a revolution of marketing concepts from the throwaway society to the make-it-better society. Mental and social adjustment would be required on the large scale, but that is inescapable if the new industrial era is to fulfill its promise of a leap ahead rather than a plunge to new despairs."

While I run an advertising agency, GeorgeCo., LLC, a Delaware Company, I am no longer in the advertising agency business. When I started my agency I started with the same impetus Richard Branson and Steve Jobs had when they started their businesses.

Do a better job making __________ by getting rid of all the crap traditionally associated with making __________.

For me, it was: do great work without all the shit that comes from making work.

Today, of course, the lip-flapping in the advertising industry (which is cost-reduction-focused not creatively-focused) is all about AI replacing people in traditional creative roles.

Many of my friends, who freelance for a living, have seen 2023 start off slow, and already they're blaming AI for their enforced idleness. Agency chieftains (and I had dinner with a few on Friday night) are worried about how they'll handle the effects of AI. Will that "giant sucking sound" be clients taking their high-volume, low-value work in-house, thus eviscerating the revenue streams of the few agencies still standing.

This is where Flora Lewis re-enters my mind.

Why can't agencies blend mass and craft? Shouldn't we be able to sell the notion of work that's as good as human-made at a price that's only a trifle-higher than computer-made?

I haven't worked out the logistics of it. But the thesis is simple. AI should be Augmented Intelligence, not Artificial Intelligence. It should do as technology does, make humans more efficient.

I realize I shouldn't offer help to my competitors who remain in the agency world. But a lot of those competitors are my friends, or at least people who have tolerated me for forty years.

Some smart agency somewhere will combine the rapid-framing and foundation building of machines with the wit, humor, intelligence, discretion and irreverence of humans. They'll combine computer and corpuscles to get a unique, plussed-up offering.

Almost as fast as a computer alone yet with human acuity and flavor. I've written a lot in this space about semiotics: the language of signs.

For instance if a business puts up plastic ropes and makes you make 17 turns to walk up to a teller or to get on a plane, they're not just treating you like cattle, they think you are cattle. We endure such indignities about a dozen times a day. If you're not already bored by all this humanizing, you might want to look at this seven-minute film on the tearing down of the old Penn Station and its replacement by urine-scented linoleum.

The Yale University art critic, Vincent Sculley says something that I think has pertinence to us in the humanity business. You can listen for it in the film: "One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat."

In every bit of work I'm involved with--no matter how tangentially, no matter how much my client won't understand what I'm flapping my gums about, I ask this simple question. How do we want to treat people? What are we saying to them? They're rats? Or they're gods?

I believe we can do better than machine-made work, or bots, or customer-service. And the bean-counters and people-cutters say we can't afford human-made. Why can't we find a middle-ground. A third way?

I think that's the blend we should be looking for. God-like rat-pellets.

Here's a five-word summation of what I mean--I'd guess a computer couldn't be this succinct.

Machine-speed with Human-creed.™

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Welcome to Free York.

As a life-long resident of the City of Mugged Shoulders (not in Carl Sandburg's words) I've spent a good part of my 65 years wrestling against the grip of parsimony. In other words, for a lot of my days and even more of my lonely nights, I hardly had two dimes to rub together. Accordingly, as the saying goes, "I throw nickels around like manhole covers."

Along the way, I learned a few things about getting by with very little tender, legal or otherwise.

I learned you could go to Zabar's virtually anytime of the day or night (especially in the old days when they stayed open till 11PM on weekend nights) and for free you could get a bisl this and a bisl that. On a good day or night, you could cop a wedge of cheese, a schtickle of cold cut, and a smattering of belly lox on a thin wafer of bagel, all for free. You could probably loop around and double-back if you were particularly famished.

As I wander I wonder. And I found a dozen places in New York, especially on what had been the "largest Jewish city in the world," the Upper West Side where you could freeload. All along Broadway from the old urine-scented Colosseum at Columbus Circle up-through the curvilinear apartment houses and wrought iron fences of Columbia University on 116th and Broadway, I think I knew everywhere you could get something for nothing just for stepping inside a store or restaurant.

I knew where I could grab a handful of pistachios. Where I could get an espresso-sized cuppa jamoke, and where I could grab a sample or nine of chocolate, as dark and bitter as a Hasid's wardrobe.

I learned bakeries where a baker's dozen (13 for the price of 12) was a matter or principle. I learned that Fairway had H&H bagels, two for thirty-five cents, a quarter of the price of H&H bagels from their very own storefront just six blocks north. I also learned where you could nibble while you shop, sample while you amble and fairly have lunch just while you were picking up your groceries.

As I got older and money was a little more plentiful, the sort of knowledge I valued changed a bit. I still enjoyed a dab of whitefish salad while I waited at a counter, but as the dad of two daughters, I learned where to find clean and safe bathrooms no matter where I was in the city. The Peninsula Hotel, btw, which rented a storefront to the chocolatier Lindt, had not only clean bathrooms, but a giant silver bowl of free Lindt candies. Take as many as you like and take some f'later.

I also learned where you could get a button sewn quickly, shoelaces if yours broke, or even a collar-stay compliments of the house if you had an interview and your collar had a mind of its own.

This morning the temperature was seasonally-appropriate (for a change) and the sun was bright. My wife and I went out for a four mile walk. When we turned around and walked homeward on Madison Avenue, my wife announced, in front of the famed Carlyle Hotel, that she needed to tinkle. We revolved through the doors and she stepped down into the famous precincts of Bemelmans bar

Ludwig Bemelmans, who went onto fame as the author/illustrator of the famous Madeline children's books was a waiter there--and by his account, a terrible one. Years later, as recompense, he painted murals on the walls of the bar that is named for him.

Next door--still in the cellar--to Bemelmans is the Cafe Carlyle. The chicest of the chic in New York High Society hotspots. The kind of place that would give Jackie O a crappy table if she came in the same night as Greta Garbo.

The pianist Bobby Short held court there for many decades playing the great American song book and singing those wonderful songs nightly. Even now when I making more money than I ever imagined, I can't fathom going there. I think I might be more comfortable interviewing undertakers at funeral homes for my incipient burial services.

However, going back to the topic (if there is one) of today's post, while I was waiting for my wife to tinkle, I heard these tinkles from the baby grand in the Cafe Carlyle.

It was all absolutely free.