George Tannenbaum on the future of advertising, the decline of the English Language and other frivolities. 100% jargon free. A Business Insider "Most Influential" blog.

Wednesday, August 31, 2022

All You Need is Love. Almost.

Tuesday, August 30, 2022

Scorpions.

Sometimes I lay in bed at night.

Unless you're Raymond Chandler, that's a bad way to start a post.

Nevertheless, sometimes I lay in bed at night.

I try to sleep but in the words of Shakespeare's "Macbeth," "Full of Scorpions is my mind."

I'll tell ya, arachnids, or whatever scorpions are, don't do much for a good night's sleep. They scratch and sting. And whatever power Melatonin possesses can be easily undone by that curvéd tale.

As I lay awake, I began counting.

Not sheep like some people do.

I began counting things much more twenty-first century. I began counting how many little LED lights were lit in my small bedroom. I counted around 15.

Reds. Greens. Oranges. Blues.

The light shining from my expensive Mitsubishi air-conditioning unit. The lights from three or four Mac devices. The lights from an alarm clock, an old internet radio, from a flat-screen TV I've never turned on. An alien blue glow from a round power strip.

All these lights.

In a space that should be dark.

I leapt from all those lights to another affect of modernity. Chimes, beeps and tones.

The trill when the dishwasher is done, the beep of the microwave, the crescendo of the dryer telling you your clothing is acceptably damp. The incessance of tones from various Apple devices telling you that someone somewhere wants you, probably a fat politician looking for a fat donation to fatten his campaign coffers so when he gets a job as a lobbyist, he is already fat.

The lights.

The tones.

The scorpions.

And then came the nightmare portion of my insomnia. The Gary Vaynerchuk portion of the evening.

With 15 lights and myriad tones, we are living in the epicenter of always-on marketing.

The lights are always on.

The noise is always on.

They do nothing for your benefit.

They serve only to press your face and nose into the brand's ever-presence.

They deliver no value, or little value.

But you're supposed to value them just for being there.

In fact, they're the metaphor for our current age of marketing. They destroy the natural world. They destroy quiet. They destroy darkness, your old friend.

They essentially take away your right to "off-ness." To quiet and quietude. To repose and thinking. To the loudest noise around you being the turning of a paper page. Or the deep breathing of your golden retriever. Or maybe the roar of an angry sea from the ocean just twenty yards away.

We have allowed commerce into our veins, into our very marrow.

Into our lives.

Into our most sanctified Sanctum Sanctorum.

We are never alone.

We are never free from the sale of the century, the Raymour and Flanaganization of our lives.

Brands have become scorpions.

They sting and kill.

And we're supposed to let them and like it.

Monday, August 29, 2022

No One In HR Will Read This. And They Don't Want You To, Either.

Many people probably think that the current spate of "Quiet Quitting" is something new. Or that "The Great Resignation" is a 2021 and 2022 phenomenon.

In the words of Hank Williams, Sr., "I've Been Down that Road Before." In fact, we all have.

Right at the start of our ongoing plague, the great historian Jon Meacham wrote an essay in "The Economist" magazine. I scanned it and saved it on my hard-drive, believing it was important, believing that Meacham's wisdom might one day come in handy.

As an aside, it doesn't matter how you define our current plagues. It could be coronavirus. It could be the plague of not believing in science. It could be the plague of lies. It could be the plague of fear. It could be the plague of an entire political party, now run on hate and lies. It could be 45-percent of our country believing in an abject liar and traitor. It doesn't matter what the plague is or where it came from, it only matters that it's with us and won't disappear for decades.

Here's the part of Meacham I think you should read and think about. Apologies for the length of the quote. Meacham has won a Pulitzer Prize and liberally quotes Barbara Tuchman, another Pulitzer winner. I ain't editing them.

"How did it end? For a long time it didn’t. There were numerous recurrences; scientists and historians still debate how the plague was brought under control. Some believe quarantine (the word derives from a 40-day period of confinement) and improved sanitation did the trick.

"The plague made no sense, and in making no sense, it helped reorder how human beings understood the world. The changes took time; as Tuchman remarked, 'The persistence of the normal is strong.'

"Yet the Black Death undermined received authority. The shift from faith in institutions — monarchies, aristocracies, papacies — to an emphasis on the individual would be accelerated in the years of the Protestant Reformation and the scientific revolution, but Tuchman posited that the roots of modernity can be traced to the disease-bearing fleas and rats of the 14th century.

"'Survivors of the plague, finding themselves neither destroyed nor improved, could discover no Divine purpose in the pain they had suffered,' Tuchman wrote. 'God’s purposes were usually mysterious, but this scourge had been too terrible to be accepted without questioning. If a disaster of such magnitude, the most lethal ever known, was a mere wanton act of God or perhaps not God’s work at all, then the absolutes of a fixed order were loosed from their moorings. Minds that opened to admit these questions could never again be shut. Once people envisioned the possibility of change in a fixed order, the end of an age of submission came into sight; the turn to individual conscience lay ahead. To that extent the Black Death may have been the unrecognized beginning of modern man.'"

But back to Quiet Quitting and the Great Resignation.

Both those terms are coined by the people and the systems that want to keep the old order intact.

The Great Resignation could just as easily, and from labor's point of view, not capital's, be called the "Great Betrayal." The supporters of runaway Capitalism and the press don't like the old order of complacent workers obeying their masters being upset. The nomenclatura "great resignation," implies, intentionally, that workers are lazy and slovenly and in the wrong.

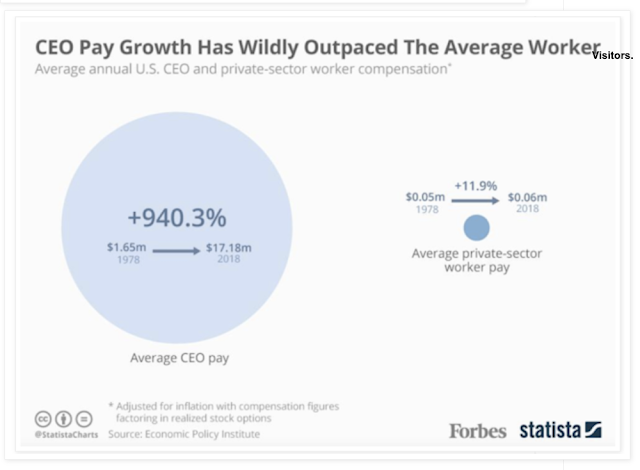

I call it the Great Betrayal because as the masters of capital have gotten richer and richer, the workers have gotten a whole lot of less. Less money. Less security. Less control (most jobs are under oligopoly control.) And less humanity. These two charts might illuminate what I mean.

Similarly, the equally-manipulative term "Quiet Quitting," which I prefer to flip and call "Quiet Stealing." In my last agency job, I routinely worked about sixty-hours-a-week while being paid for just thirty-seven-and-a-half.

All that has been stripped away today, yet the expectation that you work "executive hours," has been bolstered. Companies are getting rich, and people are "Quiet Quitting" because so many people are coerced to give free labor.

Don't take it from me, here is Stanford professor, and author of "The Great Leveler," Walter Scheidel talking about the Great Plague.

"According to Agnolo di Tura of Siena, 'so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.'

"And yet this was only the beginning. The plague returned a mere decade later and periodic flare-ups continued for a century and a half, thinning out several generations in a row. Because of this 'destructive plague which devastated nations and caused populations to vanish,' the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun wrote, 'the entire inhabited world changed.'

"'The wealthy found some of these changes alarming.' In the

words of an anonymous English chronicler, 'Such a shortage of laborers ensued

that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be

persuaded to serve the eminent for triple wages.' Influential employers, such

as large landowners, lobbied the English crown to pass the

Ordinance of Laborers, which informed workers that they were 'obliged to accept

the employment offered' for the same measly wages as before.

"But as successive waves of plague shrank the work force, hired hands and tenants 'took no notice of the king’s command,' as the Augustinian clergyman Henry Knighton complained. 'If anyone wanted to hire them he had to submit to their demands, for either his fruit and standing corn would be lost or he had to pander to the arrogance and greed of the workers.'

"Looking at the historical record across Europe during the late Middle Ages, we see that elites did not readily cede ground, even under extreme pressure after a pandemic. During the Great Rising of England’s peasants in 1381, workers demanded, among other things, the right to freely negotiate labor contracts. Nobles and their armed levies put down the revolt by force, in an attempt to coerce people to defer to the old order. But the last vestiges of feudal obligations soon faded. Workers could hold out for better wages, and landlords and employers broke ranks with one another to compete for scarce labor."

The Great Resignation and Quiet Quitting, whatever you want to call them, might each be a tempest in a teapot, a small trend blown out of proportion by the 27-hour-a-day news cycle. Or they could be a genuine subversion to the old order.

Friday, August 26, 2022

A Letter to Ad People Who Know Something Is Very Wrong.

My mentor, and if I may say, my friend, Steve Hayden and I speak with some frequency.

Steve was the Vice Chairman at Ogilvy when Ogilvy was Ogilvy. For many years he was the person behind both the Apple business while at Chiat and BBDO, and the IBM business while at Ogilvy. He was also the copywriter on Apple's "1984," a commercial many argue is the most important (and best) commercial ever.

I always get a little nervous when I talk to Steve. His brain in way up above the stratosphere, maybe up in the exosphere, maybe beyond the Van Allen belt. I am, comparatively speaking, earth-bound. I also can't believe we're actually friends. Or that he regards me as talented enough to waste time on.

Nevertheless, Steve and I speak. And Steve, and the former Chairwoman of Ogilvy, Shelly Lazarus, often send business to GeorgeCo., LLC, a Delaware Company.

Talk about pressure.

Ouch.

Steve and I had a conversation the other day. Our conversations are often like a detective at a crime scene. They hop all over the place finding and digging into shreds and shards, bits and bobs of information and observations. You have to be on your toes.

One day Steve asked me, "How's it going with Alex?" I've changed the names, but Alex is a client Steve steered my way.

I was walking down the street in Manhattan and talking to Steve. It was raining hard and I've been asked a question by Steve and can't just say, "fine." Like I said, our conversations are intense and "evidentiary." No chit-chat here.

"I think it's going well," I said. "Alex called me last Saturday morning and asked for my help writing a eulogy for a business associate of his that died."

I wasn't with Steve at that moment but I imagined a perfect James Finlayson doubletake.

"I'd say that's going well."

There's a point in this. I'm going to try to sum it up in one word, one made-up word: Centeritude.

I have a lot of clients, touch wood. And with each of them, I have earned more than a dollop of Centeritude.

GeorgeCo., LLC, a Delaware Company doesn't just write ads for these companies. Steve (and so many others) trained me to earn my spot at the center of those companies. In most cases, I sit side-by-side with their CEO or their CMO or both.

I don't spend my days discussing fonts or word choices or even small editorial fillips. I am helping companies figure out who they are, what they do, why they do it and how to express themselves.

If you go back to the great agencies and great advertising campaigns, in so many ways, in ways that go way past advertising's most-modest role of selling a particular product or service, Centeritude advertising has more to do.

By no means am I comparing the work I do to the work DDB did for Avis or VW. Chiat does for Apple. Ally did for FedEx. Ammirati for BMW.

But in my own little way, I have harkened back and created a small, very profitable agency that guides companies in the most intimate and integral manner.

My two cents says that most agencies have forgotten the potential of what agencies can do. In the words of Sir John Hegarty, advertising has relegated itself to the fringes. We make ketchup-flavored lipstick, or beer-filled sneakers. Cheap marketing tchotchkes with all the lastingness of a fart in a hurricane.

That's why, geographically, agencies are no longer in the center of cities. We're out in the fringes.

It's why our value is assessed by procurement, not business leaders.

It's why the industry competes on the basis of cost, not on the basis of brains.

It's why so much of the vitality that advertising once had has been taken over by consultancies.

And it's why the industry no longer attracts and retains the 'best and the brightest.'

The brands that have taken over real estate in my brain are all brands that were built in large measure by great advertising. Great advertising that uniquified them, clarified them, guided their behaviors, and made them 'lust objects.'

I believe that the role of advertising is not just to create better ads.

We can go beyond that.

If we get lucky, way beyond that.

We can create better companies.

Thursday, August 25, 2022

How I Got My Comic Training.

When I was just a young man in the business I got very lucky. These were the days when agencies--even ones that weren't that good--maybe even those one or two tiers down from the best--spent a decent amount of money training young employees.

[BTW, some industry friends and I are in the long process of creating an ad school. We're calling it Working Class and we've already enlisted some of the top names in the business to teach classes. We plan to sign-up a few more. By the time the frost is on the pumpkin, we'll be selling 'seats' to agencies so their people can get the kind of training that's not available today, virtually anywhere.

Watch this space for more as Working Class starts working.]

In any event, I was one of about six agency creatives--all around the same age--who joined this particular agency at the same time. Of those six I was the one chosen to go to a "Comedy Camp for Ad People" boot camp.

When I arrived at the Comedy Camp, there were other 'campers' from different agencies all over the country, including some of the most vaunted shops in the business.

I got to my assigned bunk and quickly stowed my belongings. Then one of the counselors blew a shrill whistle and ordered us all into our swimsuits and down to the lake for our first lesson.

As instructed, the first student in our small group rowed an old boat out to center of the small lake. All at once another instructor appeared in the lake and started flailing about as if he were drowning.

"Help! Help!" the faux-drowning instructor cried. "Throw me a line." Student One dutifully tossed in a life-preserver with a nylon rope attached and pulled the instructor into safety and into the boat.

That routine repeated itself four more times. Each time the drowning instructor would screech, "Help, help. Throw me a line." And each time a student would hurl the designated life-preserver toward the 'victim.'

Finally, it was my turn.

I was nervous.

Was I up to the task?

Would the instructors and my fellow students laugh at me? You screw up here and peers from agencies all over the country would mock me. I feared my career would be over before it had even properly started.

With some sweat on my brow and my pouty lower-lip a-quiver, I rowed to the middle of the lake. The drowning counselor began his very convincing flailing.

"Help! Help!" he cried. "Throw me a line! Throw me a line!"

I took a deep breath. I thought. And I thought.

Then, a metaphorical lightning bolt hit me.

I remembered why I was there. Why I was at Comedy Camp.

"Throw me a line!" The counselor screamed as he, rather convincingly, submerged into the murk. "Throw me a line!"

As he sunk, I rose to the occasion.

Rather than tossing the life-preserver, I used my head.

"Throw me a line!" he bellowed.

With impeccable timing tinged with more than a dollop of Borscht, I replied, "Take my wife, please."

A counselor on shore drummed a rimshot.

While everyone in my group got a passing grade.

I got an "A."

Take my ad school, please.

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

Life on Earth.

I remember as a boy, a seventh or eighth-grader being sentenced to Detention for being a miscreant in Latin class and failing to do my rote memorization for the (I remember) 97th straight day. Though I can still conjugate sum es est and amo amas amat, though I can still bonus bona bonum and hic haec hoc, I wasn't performing up to my Latin teacher's Draconian standards.

Though I can still recite bits of Horatius at the Bridge--"Shame on the False Etruscan who lingers in his home/While Lars Porsena of Clusium is on his Way to Rome"-- and I probably know more jokes about Latin even than I know about cannibals and cannibalism (a specialty of mine--you'd understand if you tasted my mother's cooking) I was, that afternoon, being punished.

[Latin one-liner: Why was the Latin scholar a virgin? When he was asked to conjugate, he declined.]

I remember sitting stiffly at a desk and having to translate a bit of Ovid or Cicero and struggling as the large electric clock on the wall made a silent sonic-boom tick with every torpid bit of clockwise motion. Since the very history of time time had never moved so slowly as it moved in that Detention room that afternoon. Not only was I getting whacked by Ovid and my Latin teacher, I'd get whacked by my mater and pater when I got home for having been sent to detention. O! tempore, O! mores. (And no, tempore does not mean tempura in Latin.)

As it is, as I reader of history--the history of people as well as the history behind the very formation of our planet and life, as it is, on this planet, my sense of time extends beyond what I had for dinner Tuesday last.

We tend to think that a year is a lot of time, ten years is an eon and the 246 years since the US declared its independence is an eternity.

If you reckon our species assuming its hegemony of earth dates to about 200,000 years ago (the rise of Homo Sapiens) then 200 years is equivalent to 106 seconds in 24 hours--not even two minutes. It's not even a whole frame of film at 24 fps in a 30 second spot with 720 frames.

In other words, we humans live on "I'm gonna die soon"-time, or "I have a train to catch"-time and the world lives on a different pace.

Sure, it seems now like the world has, once again, spun off its axis. The oceans are warming, millions of people are being forced to move, some scientists, like Justin Gregg, predict our species has a 9.5-percent chance of going extinct by the end of this century.

I am by no means that optimistic.

But I do read a lot of history.

Catastrophic climate change has been going on for as long as there has been life on our planet. Yes, it's different, more dire and man-made today, but cosmic time takes a long time to unfold. We don't know what will happen tomorrow, much less in one-thousand years, an amount of time for all practical purposes incomprehensible to humans.

This is not to say I am not worried. We must all act to try to mitigate our over-consumption and over-reliance on plastics and fossil fuels and other substances that increase global warming and global weirding.

But, there are no panacea here.

But read Vaclav Smil.

Resist platitudes. And simple solutions. Try to foresee unforeseen consequences.

Understand reversing human folly will take thousands of years, and in fact, has seldom ever been done. Alla iacta est.

Also, some cities will fall into the sea and probably billions of people will die.

Life has always been that way.

Sorry.

This too is a part of life on earth.

--

Horatius at the Bridge

by Thomas B. Macaulay

Lars Porsena of Clusium,

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting-day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

East and west and south and north

The messengers ride fast,

And tower and town and cottage

Have heard the trumpet's blast.

Shame on the false Etruscan

Who lingers in his home

When Porsena of Clusium

Is on the march for Rome!

The horsemen and the footmen

Are pouring in amain,

From many a stately market-place,

From many a fruitful plain;

From many a lonely hamlet,

Which, hid by beech and pine,

Like an eagle's nest, hangs on the crest

Of purple Apennine.

The harvests of Arretium,

This year, old men shall reap;

This year, young boys in Umbro

Shall plunge the struggling sheep;

And in the vats of Luna,

This year, the must shall foam

Round the white feet of laughing girls

Whose sires have marched to Rome.

There be thirty chosen prophets,

The wisest of the land,

Who alway by Lars Porsena

Both morn and evening stand:

Evening and morn the Thirty

Have turned the verses o'er,

Traced from the right on linen white

By mighty seers of yore.

And with one voice the Thirty

Have their glad answer given:

"Go forth, go forth, Lars Porsena;

Go forth, beloved of Heaven;

Go, and return in glory

To Clusium's royal dome;

And hang round Nurscia's altarsv

The golden shields of Rome."

And now hath every city

Sent up her tale of men;

The foot are fourscore thousand,

The horse are thousands ten.

Before the gates of Sutrium

Is met the great array.

A proud man was Lars Porsena

Upon the trysting-day.

For all the Etruscan armies

Were ranged beneath his eye,

And many a banished Roman,

And many a stout ally;

And with a mighty following

To join the muster came

The Tusculan Mamilius,

Prince of the Latian name.

But by the yellow Tiber

Was tumult and affright:

From all the spacious champaign

To Rome men took their flight.

A mile around the city,

The throng stopped up the ways;

A fearful sight it was to see

Through two long nights and days.

Now, from the rock Tarpeian,

Could the wan burghers spy

The line of blazing villages

Red in the midnight sky.

The Fathers of the City,

They sat all night and day,

For every hour some horseman came

With tidings of dismay.

To eastward and to westward

Have spread the Tuscan bands;

Nor house, nor fence, nor dovecot,

In Crustumerium stands.

Verbenna down to Ostia

Hath wasted all the plain;

Astur hath stormed Janiculum,

And the stout guards are slain.

I wis, in all the Senate,

There was no heart so bold,

But sore it ached, and fast it beat,

When that ill news was told.

Forthwith up rose the Consul,

Up rose the Fathers all;

In haste they girded up their gowns,

And hied them to the wall.

They held a council standing

Before the River Gate;

Short time was there, ye well may guess,

For musing or debate.

Out spoke the Consul roundly:

"The bridge must straight go down;

For, since Janiculum is lost,

Naught else can save the town."

Just then a scout came flying,

All wild with haste and fear:

"To arms! to arms! Sir Consul;

Lars Porsena is here."

On the low hills to westward

The Consul fixed his eye,

And saw the swarthy storm of dust

Rise fast along the sky.

And nearer, fast, and nearer

Doth the red whirlwind come;

And louder still, and still more loud,

From underneath that rolling cloud,

Is heard the trumpet's war-note proud,

The trampling and the hum.

And plainly and more plainly

Now through the gloom appears,

Far to left and far to right,

In broken gleams of dark-blue light,

The long array of helmets bright,

The long array of spears.

And plainly and more plainly,

Above the glimmering line,

Now might ye see the banners

Of twelve fair cities shine;

But the banner of proud Clusium

Was the highest of them all,

The terror of the Umbrian,

The terror of the Gaul.

Fast by the royal standard,

O'erlooking all the war,

Lars Porsena of Clusium

Sat in his ivory car.

By the right wheel rode Mamilius,

Prince of the Latian name,

And by the left false Sextus,

That wrought the deed of shame.

But when the face of Sextus

Was seen among the foes,

A yell that rent the firmament

From all the town arose.

On the house-tops was no woman

But spat toward him and hissed,

No child but screamed out curses,

And shook its little fist.

But the Consul's brow was sad,

And the Consul's speech was low,

And darkly looked he at the wall,

And darkly at the foe.

"Their van will be upon us

Before the bridge goes down;

And if they once may win the bridge,

What hope to save the town?"

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late;

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods.

"And for the tender mother

Who dandled him to rest,

And for the wife who nurses

His baby at her breast,

And for the holy maidens

Who feed the eternal flame,

To save them from false Sextus

That wrought the deed of shame?

"Hew down the bridge, Sir Consul,

With all the speed ye may;

I, with two more to help me,

Will hold the foe in play.

In yon straight path a thousand

May well be stopped by three.

Now who will stand on either hand,

And keep the bridge with me?"

Then out spake Spurius Lartius—

A Ramnian proud was he—

I will stand at thy right hand,

And keep the bridge with thee."

And out spake strong Herminius—

Of Titian blood was he—

"I will abide on thy left side,

And keep the bridge with thee."

"Horatius," quoth the Consul,

"As thou say'st, so let it be,"

And straight against that great array

Forth went the dauntless Three.

For Romans in Rome's quarrel

Spared neither land nor gold,

Nor son nor wife, nor limb nor life,

In the brave days of old.

Now while the Three were tightening

Their harness on their backs,

The Consul was the foremost man

To take in hand an ax;

And Fathers mixed with Commons

Seized hatchet, bar, and crow,

And smote upon the planks above,

And loosed the props below.

Meanwhile the Tuscan army,

Right glorious to behold,

Came flashing back the noonday light,

Rank behind rank, like surges bright

Of a broad sea of gold.

Four hundred trumpets sounded

A peal of warlike glee,

As that great host, with measured tread,

And spears advanced, and ensigns spread,

Rolled slowly toward the bridge's head,

Where stood the dauntless Three.

The Three stood calm and silent,

And looked upon the foes,

And a great shout of laughter

From all the vanguard rose:

And forth three chiefs came spurring

Before that deep array;

To earth they sprang, their swords they drew,

And lifted high their shields, and flew

To win the narrow way;

Aunus from green Tifernum,

Lord of the Hill of Vines;

And Seius, whose eight hundred slaves

Sicken in Ilva's mines;

And Picus, long to Clusium

Vassal in peace and war,

Who led to fight his Umbrian powers

From that gray crag where, girt with towers,

The fortress of Nequinum lowers

O'er the pale waves of Nar.

Stout Lartius hurled down Aunus

Into the stream beneath;

Herminius struck at Seius,

And clove him to the teeth;

At Picus brave Horatius

Darted one fiery thrust;

And the proud Umbrian's gilded arms

Clashed in the bloody dust.

Then Ocnus of Falerii

Rushed on the Roman Three;

And Lausulus of Urgo,

The rover of the sea;

And Aruns of Volsinium,

Who slew the great wild boar,

The great wild boar that had his den

Amid the reeds of Cosa's fen.

And wasted fields and slaughtered men

Along Albinia's shore.

Herminius smote down Aruns;

Lartius laid Ocnus low;

Right to the heart of Lausulus

Horatius sent a blow.

"Lie there," he cried, "fell pirate!

No more, aghast and pale,

From Ostia's walls the crowd shall mark

The tracks of thy destroying bark,

No more Campania's hinds shall fly

To woods and caverns when they spy

Thy thrice accurséd sail."

But now no sound of laughter

Was heard among the foes.

A wild and wrathful clamour

From all the vanguard rose.

Six spears' length from the entrance

Halted that deep array,

And for a space no man came forth

To win the narrow way.

But hark! the cry is Astur:

And lo! the ranks divide;

And the great Lord of Luna

Comes with his stately stride.

Upon his ample shoulders

Clangs loud the fourfold shield,

And in his hand he shakes the brand

Which none but he can wield.

He smiled on those bold Romans,

A smile serene and high;

He eyed the flinching Tuscans,

And scorn was in his eye.

Quoth he: "The she-wolf's litter

Stand savagely at bay;

But will ye dare to follow,

If Astur clears the way?"

Then, whirling up his broadsword

With both hands to the height,

He rushed against Horatius,

And smote with all his might.

With shield and blade Horatius

Right deftly turned the blow.

The blow, though turned, came yet too nigh;

It missed his helm, but gashed his thigh:

The Tuscans raised a joyful cry

To see the red blood flow.

He reeled, and on Herminius

He leaned one breathing space;

Then, like a wildcat mad with wounds,

Sprang right at Astur's face.

Through teeth, and skull, and helmet,

So fierce a thrust he sped,

The good sword stood a handbreadth out

Behind the Tuscan's head.

And the great Lord of Luna

Fell at the deadly stroke,

As falls on Mount Alvernus

A thunder-smitten oak.

Far o'er the crashing forest

The giant arms lie spread;

And the pale augurs, muttering low,

Gaze on the blasted head.

On Astur's throat Horatius

Right firmly pressed his heel,

And thrice and four times tugged amain

Ere he wrenched out the steel.

"And see," he cried, "the welcome,

Fair guests, that waits you here!

What noble Lucumo comes next

To taste our Roman cheer?"

But at his haughty challenge

A sullen murmur ran,

Mingled of wrath, and shame, and dread,

Along that glittering van.

There lacked not men of prowess,

Nor men of lordly race;

For all Etruria's noblest

Were round the fatal place.

But all Etruria's noblest

Felt their hearts sink to see

On the earth the bloody corpses,

In the path the dauntless Three:

And, from the ghastly entrance

Where those bold Romans stood,

All shrank, like boys who unaware,

Ranging the woods to start a hare,

Come to the mouth of the dark lair

Where, growling low, a fierce old bear

Lies amid bones and blood.

Was none who would be foremost

To lead such dire attack?

But those behind cried "Forward!"

And those before cried "Back!"

And backward now and forward

Wavers the deep array;

And on the tossing sea of steel

To and fro the standards reel;

And the victorious trumpet peal

Dies fitfully away.

Yet one man for one moment

Strode out before the crowd;

Well known was he to all the Three,

And they gave him greeting loud:

"Now welcome, welcome, Sextus!

Now welcome to thy home!

Why dost thou stay, and turn away?

Here lies the road to Rome."

Thrice looked he at the city;

Thrice looked he at the dead;

And thrice came on in fury,

And thrice turned back in dread:

And, white with fear and hatred,

Scowled at the narrow way

Where, wallowing in a pool of blood,

The bravest Tuscans lay.

But meanwhile ax and lever

Have manfully been plied,

And now the bridge hangs tottering

Above the boiling tide.

"Come back, come back, Horatius!"

Loud cried the Fathers all.

"Back, Lartius! Back, Herminius!

Back, ere the ruin fall!"

Back darted Spurius Lartius;

Herminius darted back:

And, as they passed, beneath their feet

They felt the timbers crack.

But when they turned their faces,

And on the farther shore

Saw brave Horatius stand alone,

They would have crossed once more.

But with a crash like thunder

Fell every loosened beam,

And, like a dam, the mighty wreck

Lay right athwart the stream;

And a long shout of triumph

Rose from the walls of Rome,

As to the highest turret tops

Was splashed the yellow foam.

And, like a horse unbroken

When first he feels the rein,

The furious river struggled hard,

And tossed his tawny mane;

And burst the curb, and bounded,

Rejoicing to be free,

And whirling down, in fierce career,

Battlement, and plank, and pier,

Rushed headlong to the sea.

Alone stood brave Horatius,

But constant still in mind;

Thrice thirty thousand foes before,

And the broad flood behind.

"Down with him!" cried false Sextus,

With a smile on his pale face.

"Now yield thee," cried Lars Porsena,

"Now yield thee to our grace."

Round turned he, as not deigning

Those craven ranks to see;

Naught spake he to Lars Porsena,

To Sextus naught spake he;

But he saw on Palatinus

The white porch of his home;

And he spake to the noble river

That rolls by the towers of Rome:

"O Tiber! Father Tiber!

To whom the Romans pray,

A Roman's life, a Roman's arms,

Take thou in charge this day!"

So he spake, and speaking sheathed

The good sword by his side,

And, with his harness on his back,

Plunged headlong in the tide.

No sound of joy or sorrow

Was heard from either bank;

But friends and foes in dumb surprise,

With parted lips and straining eyes,

Stood gazing where he sank;

And when above the surges

They saw his crest appear,

All Rome sent forth a rapturous cry,

And even the ranks of Tuscany

Could scarce forbear to cheer.

And fiercely ran the current,

Swollen high by months of rain;

And fast his blood was flowing,

And he was sore in pain,

And heavy with his armour,

And spent with changing blows:

And oft they thought him sinking,

But still again he rose.

Never, I ween, did swimmer,

In such an evil case,

Struggle through such a raging flood

Safe to the landing place;

But his limbs were borne up bravely

By the brave heart within,

And our good Father Tiber

Bore bravely up his chin.

"Curse on him!" quoth false Sextus;

"Will not the villain drown?

But for this stay, ere close of day

We should have sacked the town!"

"Heaven help him!" quoth Lars Porsena,

"And bring him safe to shore;

For such a gallant feat of arms

Was never seen before."

And now he feels the bottom;

Now on dry earth he stands;

Now round him throng the Fathers

To press his gory hands;

And now with shouts and clapping,

And noise of weeping loud,

He enters through the River Gate,

Borne by the joyous crowd.

They gave him of the corn land,

That was of public right.

As much as two strong oxen

Could plow from morn till night:

And they made a molten image,

And set it up on high,

And there it stands unto this day

To witness if I lie.

It stands in the Comitium,

Plain for all folk to see,—

Horatius in his harness,

Halting upon one knee:

And underneath is written,

In letters all of gold,

How valiantly he kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

And still his name sounds stirring

Unto the men of Rome,

As the trumpet blast that cries to them

To charge the Volscian home;

And wives still pray to Juno

For boys with hearts as bold

As his who kept the bridge so well

In the brave days of old.

And in the nights of winter,

When the cold north winds blow,

And the long howling of the wolves

Is heard amid the snow;

When round the lonely cottage

Roars loud the tempest's din,

And the good logs of Algidus

Roar louder yet within;

When the oldest cask is opened,

And the largest lamp is lit;

When the chestnuts glow in the embers,

And the kid turns on the spit;

When young and old in circle

Around the firebrands close;

When the girls are weaving baskets,

And the lads are shaping bows;

When the goodman mends his armour,

And trims his helmet's plume;

When the goodwife's shuttle merrily

Goes flashing through the loom,—

With weeping and with laughter

Still is the story told,

How well Horatius kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.