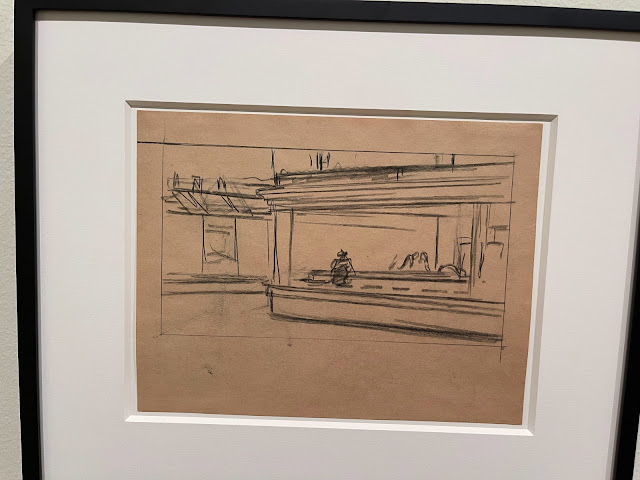

|

| Hopper showing his work. |

In 1992 I was working at an agency that won "Agency of the Decade" for the 80s. Even so, despite their creative elan, they had not kept pace with the onslaught of modernity and technology. In fact, it wasn't until 1992 that a shaggy man came into my office with this thing called a Mac and left it on my table.

Even though we weren't networked, I wasn't hooked up to a printer and we had no internet access, I was told to start writing all my copy on my new mac.

Previous to this, I'd type my copy on my IBM Selectric II and hand it to my assistant, Francine. She would retype it on a giant Wang computer, give it some sort of identification and store it on a 5 1/4" floppy disc. If I needed to make copy changes, Francine would find that disc and make the changes for me, then re-print the copy and give it to me or account.

No one trained me of course. The machine was just left on my table. I had to figure out filing and folders and organizing and all that shit.

In those days, advertising was a profession and people were treated at professionals. I had an office with a desk and facing my desk, a credenza in case I wanted to work with my back to my door.

I kept my IBM on my desk and my mac on my credenza and I went to work--on my mac.

Immediately, I hated it.

I quickly understood that writing on a typewriter is very different from writing on a mac.

Mostly because on a typewriter there is no "delete" key.

So, if I was writing an ad for a home-equity line-of-credit, I might type,

"There's money in your home that's just waiting for you to unlock."

I'd read that and roll the paper down a bit and say, "I wonder if that would be better as a question."

I'd type it this way,

"Is there money in your home that you can unlock?"

Unsatisfied, I'd roll the paper down another turn or two.

"There might be money in you home. The question is, do you know how to get it."

That would go on for about ten renditions until I got to something I liked and then I'd move on to sentence number two.

Often, I'd go back through my versions and find out that my third stab was better than my seventh. Or that hidden in stab number five was a good end line.

All that, because I had no delete key.

Eventually, I started jockeying between my IBM and my mac, swiveling in my seat from one to the other. Soon I learned how to not use the delete key.

To this day, the first document when I create when I go to work on an assignment, an ad, a pitch, anything is called "client's name running." Here I mark down and save every thought. It's my working work.

One of the things that's lost in our modern world is "showing our work." In my early days I wrote most of my copy on blue, or yellow, or pink scratch paper. That was cheaper paper that was made for drafts. With pride, we'd have client presentation copy typed onto heavier bond, without our agency logo engraved.

My point in all this is that there's a real value when you're vying for business or in presenting and selling work to showing your work.

There's a real value in showing your thought processes. (If you have them.) Not merely to show how many versions you tried, how many options you thought through, how many variables you tried. Saving those, and having those at the ready--to share with partners, bosses, clients, planner and/or account people is a good way to learn to articulate why you chose to do what you chose to do.

It's better to show a wall painted green, yellow, blue, pink and purple. And then say, "we looked at green--it felt hospital. Yellow felt like we were trying too hard to be cheerful. Pink was too assertive. And Purple too 'hippie.' That's why we chose this grey with a hint of blue."

I think the evaluateability of how you arrived at an idea, a style, a technique, a word, how you made that decision is of great value in creating and selling work.

I think it forces a consideration of how we arrive at answers. It demands a certain incisive decision-making and articulation.

I think it's why Picasso sketched this.

I think we could learn from it.

No comments:

Post a Comment