There’s a natural human urge to improve things. Or at least put our thumb-print on things.

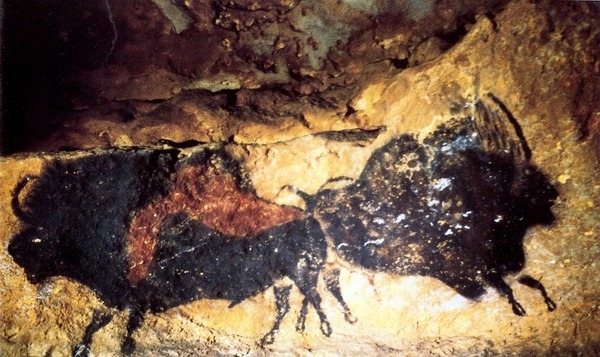

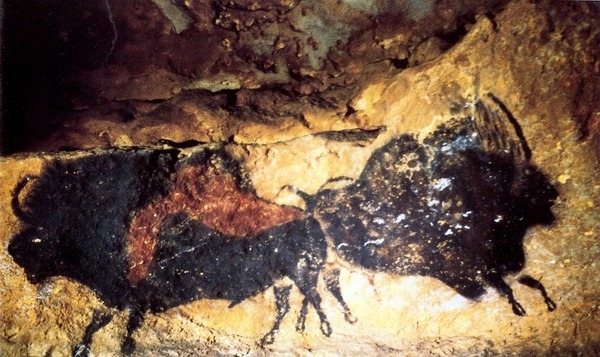

I bet even 15,000 years ago in the Lascaux caves, there was a committee of Paleolithic technocrats criticizing the work of the Paleolithic creatives.

“You call that a bison? My kid paints better than that.”

“You call that a bison? My kid paints better than that.”

Usually comments like that are accompanied by instructions on how to improve your creative work.

"Make the bison’s legs longer, his horns sharper, his back more hunched."

I like this video of Herb Lubalin explaining the give-and-take behind his rebranding of the Public Broadcasting System. You can watch it here.

The problem is, very few of us are Herb Lubalin. More often than not in getting work through the long advertising digestive track, we have to make many many compromises along the way.

A lot of those changes are good and move the work forward. They're ok. But after three or five rounds things can get, let's say, capricious, or thumb-printy.

A lot of those changes are good and move the work forward. They're ok. But after three or five rounds things can get, let's say, capricious, or thumb-printy.

Some years, or decades ago, one of the best agencies in the world was called Collett Dickenson Pearce. You can do a little digging online and see some of their work.

Or you can watch a small selection of some of their commercials here:

Back in 1975, CDP shocked the ad world by resigning the Ford account. This is business—and turning your back on money is just not done. Let me ask you, if someone offered you $1 million to ruin your reputation, would you take it? Most people would.

Here’s what Frank Lowe said on resigning Ford:

“We don’t mind presenting one campaign at a time and coming up with something else if it is turned down. But we’re not prepared to put up half a dozen campaigns to be discussed by client in committee. The outcome is rarely unanimous, and it results in flabby advertising.”

Or as Steve Hayden told me many times when I was peeved about something or other, “The best revenge is a better ad.”

But very few people or agencies or creative directors can resist the dynamic that often has us improving work to death.

I was talking to a lovely young creative team who work with me. I don’t know why, but I asked them if they had seen Fred Manley and Hal Riney’s 1963 masterpiece, “Nine Ways to Improve an Ad.”

They hadn’t.

So I showed them it:

Years ago I was blessed enough to be able to send each of my sparkling daughters to one of the best pre-schools in the world, the All Souls School, on Lexington, between 79th and 80th.

The woman who ran the place at the time was Dr. Jean Mandlebaum and she was simply brilliant.

In fact, I learned more about protecting the integrity of the work from her in about five minutes than I learned during the entirety of my career.

There was a parents' night in the auditorium one evening. A typically Upper East Side neurotic stood up to ask Dr. Mandlebaum a question.

"Before my daughter came here," she said, "her artwork sucked. After she left, her artwork sucked. But while she was here, her artwork was great. What's your secret."

Dr. Mandlebaum had a simple answer.

"We know when to take the paper away."

-->

No comments:

Post a Comment