Solomon, Solly, Soupy Weinstock had spent 177 of the last 219 evenings attending various Shivas on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, though he would venture to Shivas on the Upper East Side or even Inwood if he knew the dead party well.

Soupy--despite being named Solomon, everyone who knew him called him Soupy--was the ninth-oldest resident of his elevator doorman on West 80th Street, and by his calculus, the 21st oldest resident of the entire Upper West Side, at least up to 103rd Street, which according to Soupy was the dividing line above which was Morningside Heights.

The "Shiva thing," as Soupy called it was not the result of knowing a

lot of people who were dying or any community or religious fealty.

His reasons

for attending so many Shivas were simpler and arguably less-pure than that. For

one, Spectrum Cable, which he assiduously called Speculum Cable charged $219/month

for service and Weinstock refused, just refused to pay it. "For what?"

He'd ask, rhetorically, to his quiescent Quasar, "to watch the farkakte Knicks lose again to the Schmuffalo Bills?"

And two, Weinstock had a rugelach problem. He loved the small, sweet pastries, especially a good apricot one with a raisin or two about to plunge into his pisk and swim through his bloodstream clearing his arteries of plaque as they made their way around his system. Balloon angioplasty, feh.

Ansche Chesed, a nearly defunct Temple on West End Avenue and 100th Street, was essentially the Edward R. Murrow of the Shiva announcement business. Their daily missives sent to members and those who registered for their emails, told of dozens of Shivas a month, and Soupy, wisely for those with a rugelach fixation, had signed onto the email lists of half-a-dozen Upper West Side synagogues, including the big Kahunas, Rodeph Sholom on 83rd Street and B'Nai Jeshurun, which the kids called--with sarcasm 'BJ', which was slightly further uptown on W. 88th Street. Soupy considered BJ a veritable Yankee Stadium of religious sanctuaries. If you could Shiva there, you could Shiva anywhere.

Weinstock sat on a hard chair in the corner of the crowded living room--or dying room--and snuck two apricot rugelach into a yellow paper napkin--the fancy kind--and stuffed the assemblage into the pocket of his houndstooth blazer. A houndstooth blazer was perfect Shiva garb. Respectful, but not dull. And this particular model, which Weinstock bought at Bond's on 45th and Broadway in 1976 during the final days of their colossal semi-annual "going out of business sale," had deep pockets virtually devoid of rugelach-attaching lint. His sweets were safe there, and tomorrow's breakfast was already taken care of.

A short, heavy woman passed out prayer books to each of the sitters and Weinstock knew it was time to face the business-end of the evening. 15-minutes of actual mourning--a small price to pay for endless confections from Orwasher's and Zabar's.

Fortunately, he had seated himself next to the heavily-laden table of desserts. He heaped crushed ice into a clear plastic cup, filled it with Canada Dry Ginger Ale and as the female rabbi sang atonally like Schoenberg in Hebrew, Soupy picked at a small quart container from Zabar's of mixed nuts, successfully removing about 96% of the plain M&Ms someone had added to the assortment for color.

As the rabbi was Yiskadal-ing, Soupy spotted a blue M&M, perhaps the last of the chocolates, at the very bottom of the nut container, next to a large, broken piece of walnut.

"Walnuts are bigger now than they were when I was a boy," Weinstock thought. "It must be they feed them anabolic steroids like the schvartze baseball player, Barry Bonds. A walnut should not be the size of a crab-apple," Weinstock asserted. "That is not how the Lord meant for things to be." But on that rumination, Weinstock had reached the blue M&M and his theological disquisition was lost as if Maimonides had had a brain fart.

Weinstock stood on demand as the rabbi said, "please rise." He secretly hoped his age-related wobbling would be mistaken for some sort of quirky davaning, the ritual rocking while praying Jews have done since ancient times.

Weinstock knew no Hebrew. And even his nightly--sometimes twice-nightly Shiva attendance--hadn't taught him any. But he mumbled under his breath so other attendees would think he was holy and reading along.

In a few minutes, about as long as it would take someone to die at the end of a noose if their neck hadn't cracked during their fall, the rabbi came along and collected the mourners' prayerbooks. Weinstock said to her, "I couldn't find the Sports Section," but she wisely gave him only a small nod and otherwise no other reaction.

A few, polite moments after that, Weinstock kissed the foundationed cheeks of various wide-hipped strangers, muttered small words of condolence and made his way to the fluorescent-lit elevator with pennies stuck in the metal grating over the porthole in the protective door. In a minute he was out in the cool New York City air and walking to his junior four, less than eight blocks away.

Arriving

home, Weinstock emptied his houndstooth pockets and counted out six rugelach, a

small piece of sponge cake and a confection-sugar-topped small linzer cookie of

the type they used to sell at Grossinger's bakery on Amsterdam.

"Not a bad haul," Weinstock thought to himself.

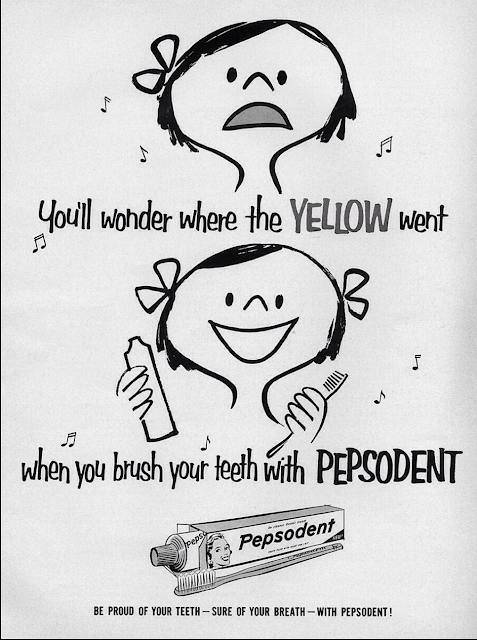

He nibbled a raisin that was hanging tentatively off a rugelach and padded to his tiled bathroom to Pepsodent his teeth with a free Oral-B given out by his dentist, Woloch, with every visit.

"Not a bad evening," Weinstock said.

In bed, he opened the Times, turning right to the obituaries.

No comments:

Post a Comment