I thought I was connected to absolutely everyone in the industry, but I wasn't connected to the person who posted these items, Scott Reames.

When you write a blog every day for almost seventeen years, you get a nose for a story. And you lose, along the way, any reticence you might once have had about talking to strangers. My nose and abeyance of reticence helps in blogging and in running my own business. I don't dally dilly or dilly dally. I go and get it.

Within minutes, I had written to Scott and requested a post from him. Almost as quickly, Scott wrote back to me and said yes.

I didn't want to burden Scott. So I made this fairly simple request.

- Make your own job. Scott saw a need for an historian, wrote a proposal and found a calling he kept at for about half of his professional life.

- Stories need consistency. Scott noticed the inevitable drift in story retelling and recognized the importance of consistency and codification.

- Likewise, companies and brands need consistency. The "meaning" of a company--if it's true--can't blow with the wind and change with every trend, fad and caprice.

- Stories win. The history, heritage and culture they capture are a "HUGE" competitive advantage.

- The next generation is important. Not just the next quarter. It takes commitment to--and money and people in for the long-haul for a brand to win over time.

- Ethos trumps execution. Executions come and go--but the foundations of a brand should endure.

- Writing things down is good. That's how they become consistent, codified and credible.

THE STORY OF JOHN BROWN AGENCY.

I was sad to learn today of the

passing of John Brown. You may not know his name, but if you know anything

about Nike history you know of his work ... a string of five words, just 19 letters,

that are at the very core of what defines Nike.

In 1976, an ad campaign for a local Portland bank caught Phil Knight's

attention. He learned it had been created by an agency in Seattle called John

Brown & Partners. Knight reached out to one of the agency's clients - the

Seattle Super Sonics - who recommended Brown and encouraged Knight to hire him.

Phil did.

[Note: I don't have access to the transcripts of the interviews I did so I'm

going from memory on all the quotes in this post.]

John told me "in the beginning we wrote one new ad each month, focusing on

the introduction of a new model, and placed an ad in Runner's World." The

ads were tech-heavy, touting the benefits of the shoe.

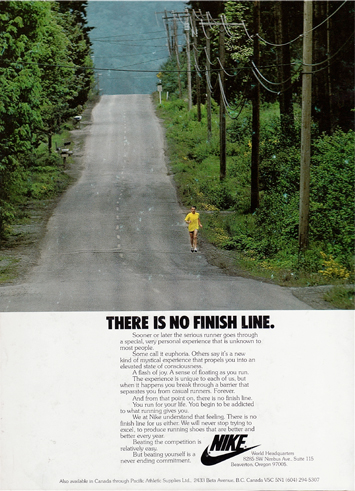

One month in 1977, however, there was no new model ready for release so Nike ad

manager Patsy Mest told Brown to "write something that makes runners feel

good about themselves."

Brown created an ad with the headline "We run a million miles a day"

that featured a lone runner on a country road. Creative director Denny

Strickland told me he wanted a "romantic" shot of a runner who was

not the center of the shot but part of the larger picture.

Photographer Bob Peterson found a location in Redmond, Washington where he

captured a man enjoying a morning run along an urban road. The man was Howard

Miller, a friend of Peterson's, who ran to work every day at the University of

Washington. In the photograph there is no discernible Nike Swoosh...the runner

is so far away you can barely see him. Bob told me the goal was to "focus

on the environment and not the runner." [Mission accomplished.]

Patsy Mest was ... let's say unenthused. So Brown presented the same image of

the runner but this time with a five-word tagline: "There is no finish

line."

Brown told me that Mest said she was "okay with it but next month we can

get back to doing our shoe ads."

But then a funny thing happened. "Runners sent letters to Nike thanking

them for supporting them," Brown told me. The ad was so popular that Nike

made a poster-sized version and soon learned that retailers were selling them

to customers. This ultimately led to the creation of Nike's own poster line

that would feature scores of iconic images (Ice Man, Supreme Court, etc.).

Several versions of "There is no finish line" soon followed, both in

print ads and in posters. It was the first Nike advertising that focused on the

brand rather than a specific product, and would become the foundation for

decades of ads to follow. Many long-time Nike veterans, including yours truly,

consider "There is no finish line" to be closer to the core of Nike's

ethos than "Just Do It."

Rest in peace, John. And thank you for sharing your amazing stories with me and

my DNA colleagues over the years.

--

Here's a bit more from John Brown himself. I haven't yet found his obituary.

John Brown • Written 6/20/2011

John Brown’s first lesson in commerce was as a ten-year-old boy, buying and reselling boxes of Christmas and holiday cards to customers in bars and restaurants in his hometown, Albany, Oregon. After high school he joined the U.S. Air Force hoping for some adventures around the world. Instead, he spent the next 3-1/2 years at McChord AFB near Tacoma working as an accounting clerk. He met his wife-to-be after a co-worker in the accounting office brought her to see his performance as an M.C. in an Air Force talent contest called Tops in Blue. He won local and regional contests and finally competed for a spot on the Ed Sullivan show. During his college years at the University of Puget Sound he worked as a bill collector for Weisfield’s Jewelers. After graduating with a BA in English in 1964 he tried unsuccessfully to find a job in an advertising agency. He was selling “Selectric” typewriters for IBM when an odd coincidence prompted Cole & Weber to give him a shot at the business. During his career there and at John Brown & Partners he has won more than 400 awards for excellence in copywriting and creative direction. His biggest regret: turning down the offer to merge John Brown & Partners with Chiat/Day when he had the chance. He has six grandkids from son Jason, a director producer and daughter Julie, a homemaker.

The following commentary was written for the author’s overdue enshrinement among the MARKETING IMMORTALS. It’s also being posted here to ensure that our readers don’t miss reading about one of the truly remarkable careers in Northwest advertising.

My advertising career was sparked to life by a fateful coincidence.

A couple of guys were making small talk at a weekly discussion group in Tacoma where a few carefully selected people gathered around a bottle of bourbon and a bowl of peanuts to talk about a book they’d all read the week before. One of them was Tom Sias, the copy chief of Cole & Weber. The other was Hal Simonsen, Chairman of the English Department of the University of Puget Sound. Tom recalled my applying for a job at his agency and that I was a UPS graduate in English so he asked if Hal thought I had the potential for becoming a copywriter. My favorite professor gave me a thumbs up. Tom decided to track me down with a job offer of $450 a month. Without that happenstance event my career in advertising would never have happened.

By the time Sias called me I had forsaken the ad business and was working as a sales rep for IBM office products in Tacoma. The job at C&W paid $450 per month, far less money than I was earning by then. But I’ve always believed you should follow your passion.

My passion led me to an office at C&W which was formerly a coat closet, barely big enough for a desk, much less a lamp so I brought one in from home. With a beginning like that, everything looked like up to me. For the next few months I worked hard and learned a lot about writing copy on projects Tom assigned to me. Until another career-changing coincidence came my way.

The office of the legendary ad maker, Hal Dixon was just across the hall from my closet-office. He and his partner, Hal Newsom, were working late and I just happened to be there, too. I overheard them trying to come up with a sequel to the locally famous billboard campaign they had created for Puget Sound National Bank. Example: George Weyerhauser saves $40 a month with a Puget Sound National Bank automatic savings account. (Bet you thought he didn’t have to.)

I worked later than they did that night and finally hit upon this campaign sequel: More and more Opticians have Puget Sound National Bank automatic savings accounts (They know a good deal when they see one.) I wrote a series of these--each with a different occupation--and dropped them on Dixon’s desk before I headed for home.

The next morning Hal came by and after I told him I had written this campaign, he asked me to move into a real office next to his friend and creative partner, Hal Newsom, who would become my new mentor.

Hal was a great teacher and one of his most valuable lessons was this: “Keep working on a campaign concept or an ad headline to make it better. Good enough is not good enough. Keep going and don’t stop until time runs out. Then go with the best idea you’ve got.”

Cole & Weber was then the biggest agency in the Northwest and over the next 11 years I had the chance to work on many of its choicest accounts. I was promoted from copywriter to creative supervisor. And then another career-changing coincidence occurred. Bob Recate, the beloved creative director of C&W’s Portland office, dropped dead.

Hal Dixon offered me that job the next day and after consulting with my wife, we were packed up and on our way to Portland 10 days later.

Hal Dixon’s advice to me about the Portland office was something like this: “The client list is made up mostly of industrial clients. They are conservative clients, not looking for wild stuff. Do the best you can without making too many waves.”

I thought to myself. “Right, just you wait, Mr. Big Guy. Somehow, I’ll find a way to make some great ads.”

Four years later, if memory serves, my team in Portland won more awards than the headquarters office. Dixon and Newsom asked me to show the Seattle staff our Portland creative work. A week or so later they asked me to return to Seattle to replace Hal Newsom as creative director.

I checked with my wife and we figured if I declined my career would have been stifled there. So back we came to Seattle.

That decision turned out to be a mistake. As much as the two Hals had expected to lead what they called Group X, a new business push with a goal of building C&W’s billing to 150 million, Hal Newsom found it difficult to give up his reins as creative director. When he asked me to change a campaign I was planning for Boeing and a couple of others I realized it wasn’t working. It grew more difficult week after week.

Then one day, out of the blue, Steve Darland called and said he had been retained by Don Kraft to find a new creative director for Kraft-Smith. I knew their work; some of it was very good. After chatting with Don, I decided to give it a go.

Don Kraft hired me to be the new creative director and member of the board of what was to be Kraft-Smith & Brown.

My stay there, however, was brief. Don Kraft is one of the nicest fellows you’re likely to meet but--despite hiring me as the agency creative director, he apparently reserved the right to change the creative work I was doing at any time and he exercised it by asked me to make some big changes to a campaign we had created for Olympic Stain.

I resigned the same day. So after a brief stay of four months, I put my stuff in a bag and headed for a tiny office I rented in a bank building in Pioneer Square.

That was the start of John Brown & Partners. I had no clients and only enough money to last about six months.

As luck would have it, an old pal of mine who ran a recording studio in Portland called to say there was a small Portland bank looking for an agency and all the good shops in town were unavailable because most of them already had a financial account of some kind. So off I went to Portland where I convinced the president of the little bank to hire my one-man agency.

Client number one was in the door. That night I called Dennis Strickland whom I had met at Kraft-Smith to handle the art direction as a freelancer. We made some powerful full-page newspaper ads that put this little bank on the map of the business community fast. The CEO took reprints of our ads to businesses around the community to drum up new accounts.

Back in Seattle, Strickland called to say he had heard Blue Ribbon Sports, a small athletic shoemaker in Beaverton, Oregon, was looking for their first ever ad agency. I immediately called the co-founder Phil Knight and invited him to lunch to introduce our fledgling agency. He told me frankly that he did not much like advertising but his dealers needed some promotional support but that I shouldn’t expect that this would ever be a big ad account.

Almost as if to show he wasn’t a big fan of advertising, he told me the story of how his logo was created. When he was starting the company that became Nike, Phil’s day job was teaching accounting at Portland State University. He found a design student and paid her two bucks an hour to design a logo. Her finished Nike “Swoosh” (now one of the world’s most recognized trademarks) cost him $75.* She was rewarded a few years later with Nike stock, now worth more than a million dollars.

I showed Phil my portfolio about a week later and he said he had indeed seen and liked the ads we had made for the upstart Portland business bank. Before I left I mentioned that Denny Strickland was doing the agency art direction and that helped close the deal. As it turned out, Knight was a runner for the University of Oregon track team at the same time Denny played basketball for the U. of O. Another fortunate coincidence.

When I got back to Seattle, Dennis joined me as the agency’s first art director. Phil hired us and client number two was in the door.

Blue Ribbon Sports--Knight’s company—sold about $25 million of Nike shoes that year. When we parted company nearly five years later sales had increased to $250,000,000.

Shortly after taking on Nike, I heard Ivar Haglund was looking for a new ad agency. Here’s where another convenient coincidence helped kick start the agency. While I was creative director for Cole & Weber, I had written and directed a TV spot for their client Rainier Bank that featured Ivar in a customer testimonial for the bank. When I called Ivar, he remembered that the bank spot had also attracted a boatload of business for his seafood restaurants. That peaked his interest. When I showed him my “book,” Ivar hired us and we worked for him until he passed away some 10 years later. He was more than a client; he was my good friend.

Back to Nike. Our work for them was a new business magnet. We won armfuls of local and national awards and that attracted lots of other clients. They included Pacific First Federal, Seattle City Light, Metro Transit, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Lamont’s apparel stores, Pizza Haven, Speedi-Lube, Everett Herald, Seattle Weekly, several political accounts, including Governor John Spellman, Senator Dan Evans and Congressman John Miller.

We also had several sports accounts besides Nike. Among them: Roffe Skiwear, Seattle SuperSonics, Precor fitness equipment, Pacific Trail sportswear, Pro-Tec protective eyewear and a tennis racquet manufacturer.

Our biggest success for Nike completely changed Phil Knight’s mindset about advertising. It happened because of a screw up in their factories.

One month their pipeline produced no new shoes for us to feature in a new ad. They didn’t want to re-run an old ad so they asked us to do something that “just pats runners on the back, a feel-good thing. It won’t make much difference in sales because we don’t have a new shoe to show.”

We answered with an ad that caused an explosion of response from runners. Our graphics were dominated by a beautiful long shot photo of a single runner on a lonely road out near Kirkland, shot by Bob Peterson. No picture of a shoe. This time it was all about running itself.

Headline: “There is no finish line.”

The copy read: “Sooner or later the serious runner goes through a special, very personal experience that is unknown to most people. Others say its a new kind of mystical experience that propels you into an elevated sense of consciousness.

“A flash of joy. A sense of floating as you run. The experience is unique to each of us but when it happens you break through a barrier that separates you from casual runners. Forever.

“And from that point on, there is no finish line. You run for your life. You begin to be addicted to what running gives you.

“We at Nike understand that feeling. There is no finish line for us either. We will never stop trying to excel, to produce running shoes that are better and better every year.

“Beating the competition is relatively easy. But beating yourself is a never ending commitment.”

That ad created an explosion for Nike in terms of customer response. Even though it was pre-email, runners wrote and posted more than 100,000 letters to Nike after that ad ran. They thanked Nike for making high performance shoes and for understanding what a lifetime of running means. Many of these Nike fans asked for a No Finish Line wall poster and wanted it to include the body copy.

A couple years later I was a guest lecturer in an advertising class and ran into a young woman who was able to recite the body copy of this ad by memory.

This massive response taught Phil Knight about the power of brand advertising. It created “the idea of Nike” as compared to another “shoe from Nike.” It was the spark of ignition that blasted the Nike brand skyward.

About a year later Nike fired us. Our office location was the reason why, they said. We were in Seattle and they were in Beaverton, a Portland suburb. They said they needed agency people who could be in their office every day. We were flying or driving down there about twice a week but they still wanted more face time.

They asked Denny Strickland to join them as ad manager. He didn’t want to move to Portland. With all the award-winning work we were turning out for them, we simply didn’t believe they would dump us. Big mistake.

A graphic designer who had done a few projects for them said he knew a couple of Portland ad makers who could give them terrific work and be there every day. Their names were Dan Wieden and David Kennedy. And the rest is history.

It was a severe blow. However, as soon as the word was out one of Nike’s competitors invited us to his office in Cambridge, Mass. It was John Fisher, CEO of the company that markets Saucony brand running shoes.

We flew back there, made a presentation and he hired us on the spot. Over the next four years we won dozens more creative awards for our Saucony ads. They loved our work but didn’t much like our office being across the country three time zones away. They parted company with us as friends.

I could have made some sort of merger deal with a Boston agency to improve our account service to them, just as I suppose I should have opened an office in Portland to keep Nike. But that would have pushed me into focusing more on agency business affairs than making ads. I liked doing creative work more than fooling with financial reports and personnel management so I kept making ads. And hoping new luck would break our way.

Before long my Cole & Weber friend Dick Hadley called to say he was leaving the agency and was taking Puget Sound Bank with him, since C&W had won the much larger Sea-first Bank account. Dick asked to join our agency. That changed our name to Brown & Hadley and Partners.

Over the succeeding three years we made some powerful advertising for Puget Sound Bank, some of my best work for any financial institution. The concepts were based on an overwhelming fact. Puget Sound Bank was the last major commercial bank left around here. All the others had sold off to even bigger banks from other towns in other states. We turned that to our advantage. We showed big banks of depositors’ money being stuffed in sacks marked Sea-First and put on trains headed for California. Same for other competitors. The second prong of our campaign promised to make a contribution to a fund to help clean up the waters and shorelines of Puget Sound for every deposit customers made to their accounts.

Money poured in. It caught so much of Key Bank’s attention they eventually made a buyout-merger offer to Puget Sound Bank they couldn’t refuse. Goodbye Puget Sound Bank.

Game over. With the loss of the bank income and the rest of our clients cutting back or canceling budgets in a difficult economy, we could no longer cover our costs. Brown & Hadley closed its doors for the final time.

It was a wild ride and I enjoyed nearly every minute of it. I hired some outstanding people in my career, notably Bill Borders, Dave Newman and Mark Norrander in Portland and Palmer Pettersen, Steve Sandoz, Dan Wurz and Denny Strickland in Seattle. We had perhaps too lively a time doing good work and enjoying ourselves perhaps a little too often.

I decided to stay in the business as a freelance writer, creative director and consultant. I’ve been doing that for clients and agencies ever since.

And I’m still looking for work.

* This is what Scott wrote to me just a minute ago, as I showed him the draft of my piece.

I absolutely LOVE that John Brown wrote that Phil Knight paid $75 for the Swoosh design. Phil actually paid $35. Voila, you have the crux of what I was talking about...stories that drift! And for all I know, Phil might actually have told John he paid $75. Other than my realization that I failed to include a close parenthesis in one paragraph of my post, it's fine with me for you to post.

No comments:

Post a Comment