No matter what you do for a living, even if you're the Librarian of Congress and you're surrounded by a billion books, there's very little chance that you'll read anything better--today or any other day--than what my friend, Debra Fried, has written below.

Debra wrote a short column a few weeks ago about a bike accident and life.

Mostly life.

I quickly wrote her a plaintive note. "Won't you write something for my blog? Please."

The best thing about advertising--regardless of what era you're from--is that you're likely to get to work with at least a few people who have a genuine soul. Souls are as scarce as microchips these days. The supply chain seems to be snarled.

Just an hour ago, Debra sent me the story below.

It's an important story.

About love of the craft of advertising. Love of doing a job well. Love that can bloom between partners, and how that love can spread through families and last forever.

If you're lucky in life and business, you're lucky not in love, but lucky to have love. It's the one commonality of success. Love of what you do and love for the people you work with.

Thank you, Debra.

For sharing the love in your heart and soul.

Love, me.

|

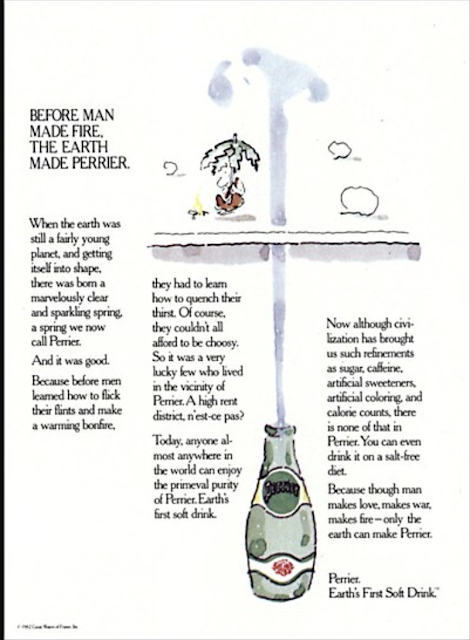

| A small, very small selection of work from Waring & LaRosa. |

The

Last of the Great Fucks by Debra Fried.

I was a junior

copywriter with a window office, which didn’t make me exceptional – it just

made it the 90’s. Everyone at Waring

& LaRosa had offices, except for the assistants – and they hung out in our

offices almost as much as we did. I had

been told to settle in, which took all of five minutes, since I had only a

rolodex, a stopwatch and an empty notebook, on which, without a hint of irony, I’d

drawn a lightbulb with lines emanating from its center.

I

was looking out the window toward 54th Street when I heard a voice

behind me. “You Debra?” I turned to see

a man who was about my height. He had an

impressive head of silver hair, dark brows, and a mustache, the colors of his

hair and brows, as if they’d mated and produced a perfect child. If he’d been

tall, he’d have been movie-star handsome.

Instead, he was compelling – the kind of face I’d have been riveted to, had

his hands not been so distracting.

He held a blue

kneaded eraser, which, like a juggler’s pins, was kept in constant, fluid motion.

He stretched it between his hands, as thin as the string in a game of Cat’s

Cradle. “I’m your fuckin’ partner,”

he said, and balled it into his palm, giving it a few quick pumps, before

pulling it back into a bubblegum-like string, then twirling it, lasso-style, around

his forefinger. Someone walked past and clapped

him on the shoulder. “Hey, you fuck!” he called after the guy, then shook his

head, smiling. “I love this fuckin’

place.” I smiled, not sure how to

respond, but he continued. “The fuckin’ account girl has a brief …”

“You mean she has

a fuckin’ brief?” I said, with a conspiratorial grin.

“What?” he asked,

looking genuinely puzzled.

I waved my hand as if to erase my attempt at a

joke, my mind racing for a new topic.

“Anyway,” he

continued, it’s a good one – it’s AMC – you know that channel? It’s

cable.” Someone yelled “Lou!” from down

the hall and he shook his head with a smile. “These fucks,” he said, and I

tried to make a face that suggested I understood the fucks. He stepped over to the window and said, “The

fuckin’ Lipstick Building. Who names a building after a cosmetic? Ha!

xxxxxxxxxPeople.” The same guy yelled “Lou” again, and

he shook his head. “I gotta go, Pal.” As he turned and smoothed his hair, I

couldn’t help but be a little thrilled at the “Pal."

Later that

morning, we sat in Lou’s office. Actually, I sat. He paced,

whipping his eraser into a frenzy. His office had a drafting table instead of a

desk. Lou was about 20 years older than

me and had worked at agencies like Levine and Scali; names even I knew enough

to use with reverence.

“We gotta put Frank Sinatra in the

commercial. I fuckin’ love Sinatra. He

wasn’t tall, you know. Little fuckin’ peanut, like me.”

“But this is AMC – it’s

supposed to be about classic movie heroes. And Frank Sinatra’s not

really heroic,” I said, with a little laugh. His long beat of silence

made me wish I could take it back.

“Frank Sinatra’s not a hero,”

he repeated, to a spot on the wall above my head. “Ok. Fine. That’s

great, Debra.” He looked so offended, I wasn’t sure if he wanted to

hit me or cry.

“How about Marlon Brando?” I

asked hopefully.

“Brando! Hah! I fuckin’ love Brando!” he

announced, pausing between each word. “I mean, before he turned into

a fat fuck. Yeah, we gotta use Brando.” And with that suggestion, I began

to gain the acceptance of Lou Colletti.

Lou used his eraser for more

than just stretching and twirling. As we

came up with ideas, he’d hunch over his table, sketching. It took time, and back then, we had more of it

than we do now. He drew characters into

the frames of storyboards, mulling, shaking his head, furiously erasing, then

redrawing with a level of concentration and thought that doesn’t happen with

the click of a delete button. I could always tell how much he’d worked by how

blackened the eraser had become. Every

few days, he’d open a fresh one, slowly kneading it from rectangle to ball, as

if getting to know a new friend.

As

he worked, he’d mutter to himself – “fuck a duck, man, fuck a fuckin’

duck.” Lou used “fuck a duck” to express

everything from wonder; “Look at those tulips. Middle of Park Avenue. Fuck a

duck, man,” to joy; “Fuck a duck! They bought the spot!” to heartache. When our

favorite takeout place closed, he stood on the sidewalk uttering “fuck a duck”

so sadly, you’d think he’d lost a beloved pet.

At my first Waring Christmas

party, Lou stood near me, looking pale and a little

bleary. Unthinkably, his hair didn’t look good. “Fuck! How could I be sick at the

fuckin’ Christmas party? Well, I’ll just have one scotch, then I go

home. I promised Joan.”

An hour later, he led a

conga line in and out the door, a red Macy’s bag on his head. As the

party wound down at midnight, he taught a shy, awkward girl to two-step. “You

got some real fuckin’ rhythm, Pal,” he said, and she giggled as he dipped her.

A few days later, we stood at

the mirror in his office, elbowing each other out of the way, as I fixed my

lipstick, and Lou combed his mustache. He pulled a bottle of Visine out

of his pocket and leaned his head back.

“How is it that you put that

stuff in 15 times a day and always miss your eyes?” I asked. “Shut the fuck up,

Debra,” he answered, giving the bottle another squeeze, as more liquid ran down

his face. He straightened his head, looked at me for a second, then spoke.

“The doctor says Joan has

to have a fuckin’ operation. She got a little fuckin’ thing – they

gotta remove it – the guy says it’s fuckin’ simple,” he said. then added, “Come

on, let’s go out.” Amongst the many

things we did in those days, was leave the office at lunchtime.

We did a little shopping,

mostly for my stuff, because Joan had already bought presents for their boys. As we stood in front of Saks with throngs of

others, I said I thought it would be fun to be a window designer. He looked at me curiously and said, “But we

already have the most fun jobs.” He grabbed

my arm and steered me toward St. Patrick’s Cathedral, saying, “You gotta

make one stop for me, now, Pal.”

“I’ve never been inside,”

I said as we climbed the steps. He stopped. “You’ve never been to St.

Patrick’s” he answered. Lou’s habit of

repeating what I’d just said to underline its ludicrousness both annoyed and

amused me. He shook his head, unable to

process my confession. “Wow. Sometimes you kill me, Pal."

We entered to a hush that was

immediate and mighty. We stood in the

back. A homeless man crossed himself, then slid into a pew. He nodded to guy in a suit, who returned the

gesture with a small smile. Strangers out there, brothers in here. I looked to see if Lou noticed, but he was gazing

to our left. He took my arm and led me toward the candles.

“See, you put a little money in

here,” he said softly and stuck a few bills into a cup, “then you… well, this

is for Joan,” he said, lighting the match. As he lit a candle, a tear landed on

his mustache, where it quivered, like a drop of mercury. “She has a brain

tumor,” he said, looking at the flame. Then he met my eyes and whispered, “I’m

scared.” We stood quietly for a while, surrounded by flickers of hope and

desperation.

The operation took eight hours

and the doctor said they got it all. Lou took some time off and eventually,

Joan recuperated, except for a slight loss of hearing. When he came back, we had a new campaign to

do; this one for Fisher-Price toys. There

were a few spots we needed to bang out quickly, before doing a print ad for

Mont Blanc. As the sun went down, I sat,

typing, Lou sprawled on a chair, his feet on my desk. Joe LaRosa and Saul Waring, who owned the

place, stopped in front of my door as they buttoned their coats. “You guys going home soon?” Joe asked. Lou told him how much we had on our plates,

and he said, “Ok, do what you have to.

But try to get home.”

Saul and Joe made the rounds

most nights before they left, like parents, making sure their kids were tucked

in. I told Joe once how I appreciated

the way he said “go home” and he answered with a shrug, “It’s really for the

good of the agency. We want our people happy.

Go home, go out, have a life. Your work will be better.” Waring & LaRosa won some awards, but they

were by-products, not the focus. Saul and Joe put brands like Perrier and Ragu

and Fisher-Price on the map and they made a lot of money in the process. All

while creating an atmosphere where people liked coming to work almost as much

as they liked each other.

After a while, I moved to another

agency, and Waring & LaRosa, along with Lou, and his fucks, was bought by

Y&R. A couple of years later, Lou,

who’d been laid off, came to my office to meet me for lunch. He looked around at the open seating and

said, “This was the fuckin’ death of advertising.” A guy in a baseball cap glanced up, then back

at his screen. “They make you sit like a

bunch of fuckin’ accountants,” he continued. “How do you work like this?” The

guy looked up again, this time, with obvious annoyance. “Sorry, man, we’re on a tight deadline,” he

said, and I steered Lou to the kitchen before he could say “fuck a duck” in a

not-joyful way.

We went to lunch, and I asked

if he was going to look for something new. He twisted his ring and said, “Nah…

no more advertising for me, man. I did my time.” He didn’t need to say it – we

both knew it – advertising had changed, and he hadn’t. And wouldn’t. And

couldn’t.

Lou was an ad guy. He wouldn’t have been caught dead using phrases

like “consumer journey” or “brand values” and would have glazed over during

conversations about click-through rates or the merits of paid vs organic. He

knew how to sell a fuckin’ toy. A fuckin’ pen. A fuckin’ bottle of water. And

he did it really well.

“So, what do you think you’ll

do? Retire?” I said. “Retire?

Debra. What do you think, I’m some old fuck in a pair of stupid shorts?”

he said. He leaned back, eyeing me

sheepishly. “Know what I’m doing? I

already started. I’m working for a fuckin’ hospital. Hackensack – best fuckin’ place

in Jersey. Look it up.”

“Oh, cool,” I answered. “So,

you’re volunteering?” He sat up, as offended

as he’d been when I’d said Sinatra wasn’t a hero.

“Am I volunteering.” He sighed,

exasperated at my lack of understanding. “Debra. Do I look like a fuckin’ candy

striper? I’m working.” He took a

sip of his coffee. “I’m a security guard. And the best part is that the parking

lot is so big, they need somebody to drive people from their parking spots to

the front door – you know, the ones that are getting procedures and shit.” I didn’t know how to respond. But then he

continued. “I take them in my car. And when I get them to the door, I hop out

and no matter who they are, I give them a hug and tell them they’re gonna be ok.

Even the fucks. Some of these people, Debra, I’m the last person they see

before they go in. They need a little

boost, you know?” I tell him that if I were in that position, he’d be exactly

the person I’d want to see me off.

“You know, all I ever really wanted was to be happy, and to

make other people happy,” he said. “Now that’s

what I do. And I get great fuckin’

benefits,” he added, “so who the fuck needs advertising?”

He walked me to my

building and jangled the change in his pocket as we talked. That was when I

realized what was different. His hands were empty. He gave me a hug that hurt,

and as he walked off, turned for one last wave. I returned it, and my smile was

big, but I felt a little empty. Because I

knew how much I’d miss the sight of a kneaded eraser being stretched to its

limit, by the hands of a fuckin’ master.