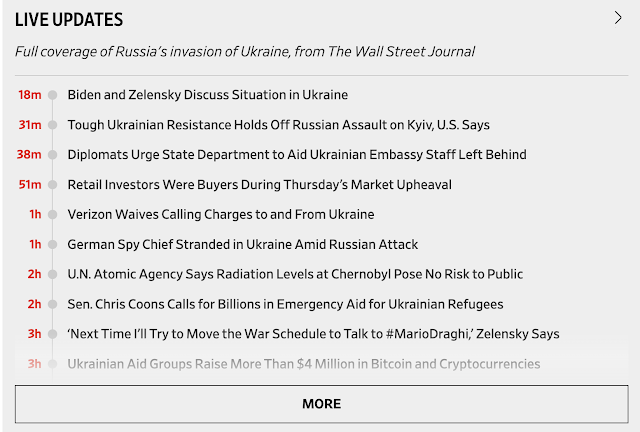

When I was growing up in the advertising business, there was an unwritten, unspoken rule. It was never carved in marble or engraved in bronze. It just was. It just was based on the thousands of great ads we'd read and studied by the people who made the modern ad business the modern ad business.

The writers of DDB, PKL, Carl Ally and more. When you read their ads in the awards annuals (ads that actually ran, by the way) their last lines always contained a smile or a poke. They were always warm and surprising and often funny or witty.

We labored over last lines. The saying went, "last lines are a reward for the reader for reading your ad."

It was a pretty good way of thinking about what we do.

In today's industry--and by today, I really mean most of the last thirty years, we've forgotten this.

I am not just being semantic.

But in my lifetime, we've gone from calling people people, or readers, or viewers, or customers, or audiences to calling them targets. Targets we put in buckets.

Calling someone a target is no way to engender trust.

The very basis of humanity--this is going back to the Torah, which is just about the first foundational text ever written--is treating people as you wish to be treated.

Not as a target.

This is something we need to think about as an industry.

Are our ads to besiege people or are they to serve people?

Are our ads to pound away at people until we wear them down, or are we to soothe, comfort and support them?

Are our ads to insult people with bait and switch tactics or are our ads showing them honesty and respect?

Are we verizoning people to mince meat, or are we showing kindness?

If you take a moment a read a novel from the early days of the English novel, say something by Laurence Sterne or Henry Fielding, they often talk directly to their readers and use the phrase "dear reader."

In the great Bob Levenson's obituary in The New York Times, when he was asked how he wrote copy for so many Volkswagen ads, Levenson said: "I always started by writing Dear Charlie, like writing to a friend. And then I would say what I had to say, and at the end I would cross out Dear Charlie, and I was all right.”

Let me underscore something for you: like writing to a friend.

The highly-controversial sociologist, Charles Murray, wrote a book a few years back called "Coming Apart." The Times' op-ed columnist David Brooks wrote about it here, in a column called "The Great Divorce." Let me pick out a piece or two of Brooks' column for you to think about--not toss aside.

1.

His story starts in 1963. There was a gap between rich and poor then, but it wasn’t that big. A house in an upper-crust suburb cost only twice as much as the average new American home.

2.

Today, Murray demonstrates, there is an archipelago of affluent enclaves clustered around the coastal cities, Chicago, Dallas and so on. If you’re born into one of them, you will probably go to college with people from one of the enclaves; you’ll marry someone from one of the enclaves; you’ll go off and live in one of the enclaves.

Ah, I'm being abstruse again.

Here's some clarity:

I think the advertising industry has forgotten about the humanity of humans. I think we are guilty of not getting out of our enclaves. We think the world ends in Williamsburg and anyone outside of our little circle is less than human.

So we treat people like cattle. I think we think that if we show people dancing because they have a new Swiffer dry mop, or gushing over their unreliable-and-extortionate cable service, or being impressed by the balloons in a Hyundai showroom, sooner or later people will believe it. Because deep-down we don't know our "target" and/or we believe they're dumb. Or at least easily gulled.

It might be worse than that. We might just be creating those images because they make our clients feel good as they rip people off.

Back to Murray, we in advertising, it sadly seems to me, are living in a world largely estranged from the reality of everyday life. The vectors of DEI efforts have not dented this hermetically-sealed cocoon. We've just brought more diversity to our industry-wide estrangement and myopia.

We don't know real people. We know archetypes, targets and victims of powerpoint.

The question is, are we bringing understanding, kindness, warmth and empathy to our work? Or are we making expensive films of models and gleaming smiles that are as human as a manikin?

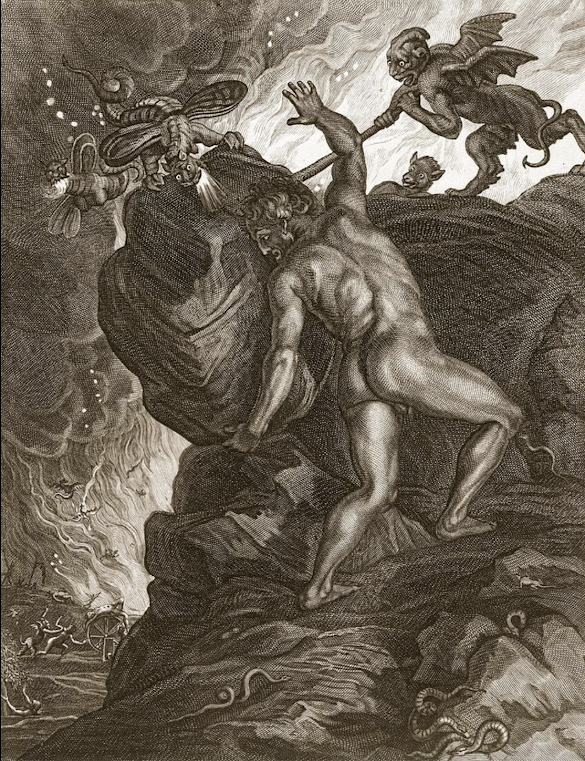

When we, as an industry, create a thousand messages a day with which to assault our target like Gulliver stung by ten-thousand Lilliputian arrows--are we treating people as people or as targets?

We used to talk about issues like this in advertising. How we're treating people. What we're doing for people. How we're making them feel. How we're comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable.

But now our conversations are on tracking people like escaped convicts except we use data and cookies and technology rather than feral bloodhounds. Now our conversations are about our $4000/night Cannescommodations and who's won 700 awards when there haven't been seven good commercials done in the last seven years. Now we talk about NFTs and metaverses and which celebrities' artificial ass implants look the most genuine.

To paraphrase David Ogilvy, we are once again treating the consumer like morons.

We are forgetting that ever since time began--when the first hominids took their first step into bi-pedalism--humans are humans.

We like to laugh, love, learn, lust, labor.

We don't like to be yelled at and demeaned.

--

About four times a week, I get a message from someone I don't know asking me to mentor them or, at least, to teach an advertising class.

With some wise friends, we are planning in the fall to launch a school called "Working Class." It will aim not to teach the "how" of advertising--it ain't about last year's awards or some photoshop technique or how to tik a tok.

It will be about some things that are much more important: the "whys" of advertising.

Why do we advertise? Why is it important? Why does our work matter? Why has advertising created more wealth than perhaps any industry other than prostitution?

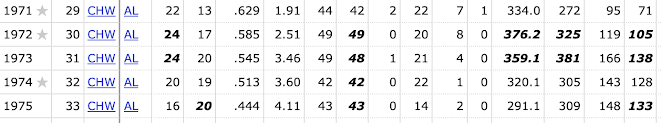

It will be, as it should be, expensive. But you can save yourself a boat-load of money on the course. Just read the Volvo ad above by Ed McCabe.

Think about how we don't talk about payment books today. Or how long cars last. Or how people drive. Think about how that Volvo ad is about real people who live with sweat and who work hard and who have hopes and dreams. Think about ads written by humans for humans.

That's the course.

Right there.

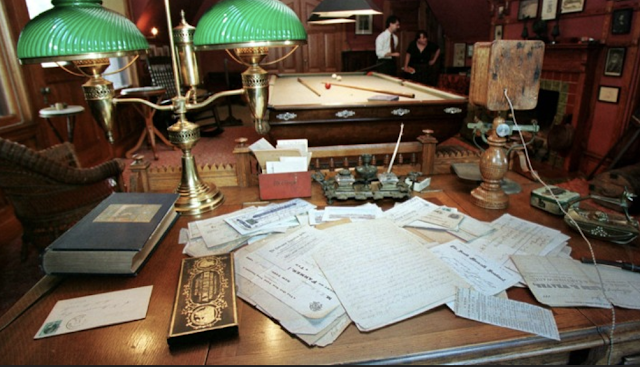

The Guinness team were reviewing posters for the Good Things Come To Those Who Wait campaign which they’d spread out over the snooker table.

David studied them and there was a long silence.

Finally, he folded his arms and sighed ‘Oh dear. This is terrible.’

The team gulped.

Heads dropped.

I’m pretty sure one junior planner nearly fainted.

Then a grin gradually appeared and he asked ‘How can we play snooker if this great work is on the felt? Would you mind moving to the boardroom? Richard and Arg normally have a rack about now.’

Laughter erupted.

Proofs were relocated.

David returned to his office.

Feet on the desk.

Pen to pad.

David always defended our space to play and our time to think.

(In the 14 years I was at AMV BBDO I never worked a weekend and left most days at 17.30.)

Dave Buchanan later advised me one day when we were waiting for the kettle to boil ‘Time. Money. Space. Talent. You need all four to do great work, Mike. If you can fight for all of those things the agency will fly.’

Creating and defending a process ensures great work.