My wife is more than a bit of an art fiend and we headed right for the Rijksmuseum, which has more Dutch Masters than your local Te Amo cigar shop. Literally mile after mile of brilliant works.

It's no wonder, really. While the rest of Europe was under the crushing conservatism of the Roman church, Protestant Amsterdam was in contrast much more open and, yes, liberal.

The Dutch were also early adopters of liberal financial practices that made it easier to raise vast sums of money for commercial ventures. That's how, really, they surpassed the Portuguese to become the world's foremost trading power, dominating the East Asian spice trade until their "possessions" were wrested from them by the Japanese during the early days of World War II.

Even more striking to me than the Rijksmuseum was a much smaller museum down the cobblestones dedicated to Van Gogh. There I learned something that continues to startle me. Van Gogh painted more than 70 paintings in the last 70 days of his life. That's right, more than one painting a day.

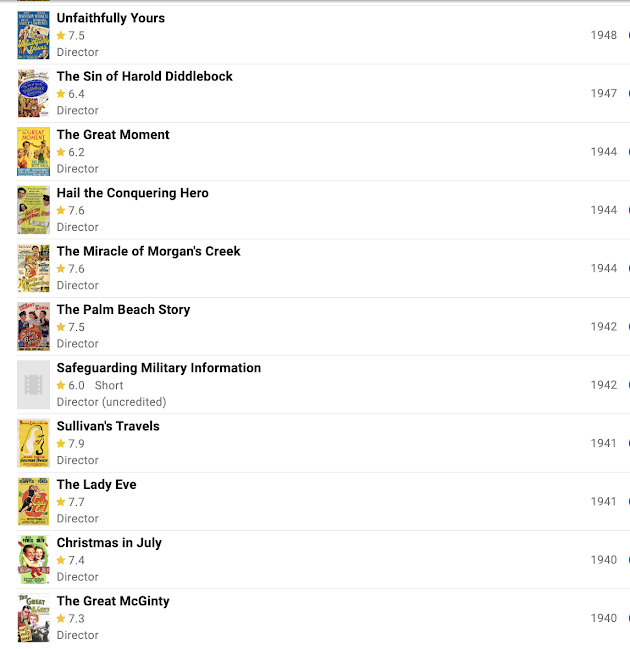

To my blue American eyes, the apotheosis of creative production had always been achieved by America's greatest comedic writer and director, Preston Sturges.

In just eight years, he wrote and directed ten great comedies. While it's hard to find a list not afflicted by a recency heuristic or some other sort of bias, many people consider The Lady Eve, Palm Beach Story and Sullivan's Travels three of the greatest movies ever. And others on the list, like McGinty, Miracle, Christmas, Conquering and Unfaithfully, are fall-off-the- Raymour & Flanagan-sectional-funny.

I rate the first 30 minutes of "The Sin of Harold Diddlebock," the greatest 30 minutes in film history, though admittedly not all that many people agree with me.

They're wrong.

My point in all this though has nothing to do with Van Gogh or Sturges and everything to do with Wieden & Kennedy. Or at least a slogan by Wieden & Kennedy.

When it comes to being creative--or trying to be creative--"Just Do It."

Van Gogh painted 77 masterpieces in 70 days.

We have a hard time doing 77 banner ads in 70 days.

And Sturges made eleven movies in eight years while being drunk 92% of the time.

This is not to suggest you should be drunk 92% of the time.

It is to suggest that as individuals and as an industry--an industry full of more people watching than doing--that we get over ourselves. That we pay less attention to perfection and more attention to genuine feeling.

When I was still working for "the man," I was often burdened with more than my fair share of work. When that was the case, and it was almost always the case, I had a way of handling it.

I would get to my desk at seven.

I would pick up the first brief and say, "this will be done by 8:30."

I would pick up the second and say, "this will be done by 11. By the time most people are strolling in."

By lunch or mid-afternoon, I had done a month's work. Or a week's.

I never pretended I was building the Hoover Dam or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Just a long copy ad on cloud migration. Or three spots on IBM Watson. Or another long copy ad on why a company's planes fell from the sky and what they were doing about it.

All of these assignments were important to me and to my clients. But not so important that I treated them like I was cutting the Koh-i-Noor Diamond.

Again, back to Wieden & Kennedy.

Just Do It.