Back almost thirty years ago a writer I had scarcely heard of, Joseph Mitchell, died. He had been with The New Yorker since the late 1930s. Accordingly, in tribute to him, the magazine ran a spread or two of notable writers saying how much they admired Mitchell.

I went out and bought every one of Mitchell's books I could find. And I read them. A couple of times through. (There were still bookstores in New York back then. Including Books & Company, which sold signed copies of Mitchell's books.)

A story emerged about Mitchell. He had spent from 1964 to 1995 at the New Yorker without publishing a word. He came into the office every day, and he typed. But no one saw any writing and nothing was submitted to the magazine. Other writers took to going through his garbage pail at night to see what Mitchell was up to.

They came up empty.

In certain rarefied writerly precincts, Mitchell's flame has never died out. The New Yorker Festival regularly pays homage to him. They organize a trip to a graveyard he wrote about on Staten Island. Or they gather to talk about his great writing on the long-gone greasy-spoon "Sloppy Louie's."

About once every two years or so, someone finds a stray piece of never-before-published Mitchell. And the New Yorker duly publishes it. I would imagine their readership that week leaps. As if Playboy uncovered some forgotten cheesecake featuring Marilyn Monroe or Dorothy Stratton.

In The New Yorker's February 16, 2015 issue, they published an essay by Mitchell, a "personal history." It was called "A Place of Pasts." I've read it probably once each month since it was published seven-and-a-half years ago.

It's the opening sentence that gets me. It hits me like Alexander being shish-kebobbed by a Persian javelin.

"In the fall of 1968, without at first realizing what was happening to me, I began living in the past. These days, when I reflect on this and add up the years that have gone by, I can hardly believe it: I have been living in the past for over twenty years—living mostly in the past, I should say, or living in the past as much as possible."

By my math, Mitchell was around eighty when he wrote those words. I'm 15 and a half years from that mark. But I think I'm beginning to understand what Mitchell was getting to in his essay.

(By the way, I'll paste the article--because I'm nice--at the end of this post. However, if you can afford it, subscribe to The New Yorker. Or something else you like. Supporting thinking is our civic responsibility.)

Lately, I've been saying a sentence to myself that in a backhanded way sounds like it might have been written by Mitchell himself. I've been calling myself, "A man out of time."

I mean that sentence, unfortunately, in two ways.

One, though I am very healthy and fit, I have a bit of a premonition that things are coming to an end for me. Maybe because my father died at 73 and his father at 56, I don't foresee an Ichabod Crane future for myself.

I don't have the tell-tale creases in my earlobes that portend a coronary, or the perhaps apocryphal line on the back of my neck that medievally is supposed to signify doom, but I just feel "done." I've done enough. My kids are fine. I've got money in the bank. And I have no material wants. And no one really needs me. It's being un-needed that's the worst.

If the great scorekeeper decided to pen my name, I wouldn't put up a fight. I'm not much looking forward to the emergence of American Nazism and it seems to be coming, and inexorably. Nazism of any stripe is rarely good for Jews. Given my mercurial nature, I would not last long under president Marjorie Taylor Greene. I don't think we'd hit it off.

The second meaning to my ears of "A man out of time," is the more conventional one.

That I have a set of standards and behaviors that no longer belong in today's world. Worse, the way things are done today offend me. That's too mild. They make me mad.

Here's where, not above, I won't go gentle into that good night.

I won't shrug my shoulders and show up late.

I won't half-ass work and say to myself, "it's good enough."

If I promise five, I'll deliver eight. If I promise Wednesday, I deliver Tuesday.

Also, I'll research things on my own. I won't trust a brief. I don't trust anyone else to do what I consider my province.

All those behaviors mark me as an anomaly. They're the behavioral equivalent of wearing knickers and a pince-nez or jodhpurs and a riding crop. I'm anachronistic in a world that seems content to phone it in. On a network that seems to drop three calls in five.

I read somewhere not long ago something I liked.

- A meeting should be no longer than twenty minutes.

- A powerpoint no longer than fifteen pages

- And an email no longer than fifty words.

In other words, show respect for your viewer.

Sorry about this post.

I'm getting old.

--

Personal History FEBRUARY 16, 2015 ISSUE

A Place of Pasts

Finding worlds in the city.

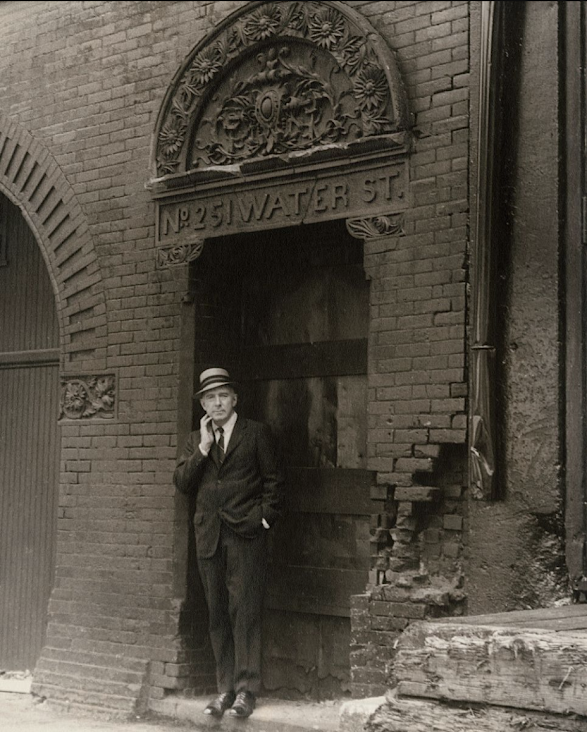

Joseph Mitchell was born in 1908 into a prosperous family of North Carolina cotton and tobacco growers. At the age of twenty-one, he came to New York City to pursue a career as a writer, and he started contributing to this magazine four years later. In the late sixties and the early seventies, he began writing a memoir. What follows was intended to be the third chapter but was never finished.

In the fall of 1968, without at first realizing

what was happening to me, I began living in the past. These days, when I

reflect on this and add up the years that have gone by, I can hardly believe

it: I have been living in the past for over twenty years—living mostly in the

past, I should say, or living in the past as much as possible.

And now, right away, before I go any further, I

must interrupt myself and say that I am not entirely satisfied with the phrase

“living in the past” as a description of my way of life—it makes me sound like

some kind of sad old recluse—but living in the past is the closest I can come

to it; I hope that my meaning will become clearer as I go along.

And I should also say that when I say the past I mean a number of

pasts, a hodgepodge of pasts, a spider’s web of pasts, a jungle of pasts: my

own past; my father’s past; my mother’s past; the pasts of my brothers and

sisters; the past of a small farming town geographically misnamed Fairmont down

in the cypress swamps and black gum bottoms and wild magnolia bays of

southeastern North Carolina, a town in which I grew up and from which I fled as

soon as I could but which I go back to as often as I can and have for years and

for which even at this late date I am now and then all of a sudden and for no

conscious reason at all heart-wrenchingly homesick; the pasts of several

furnished-room houses and side-street hotels in New York City in which I lived

during the early years of the Depression, when I was first discovering the

city, and that disappeared one by one without a trace a long time ago but that

evidently made a deep impression on me, for every once in a while the parlor or

the lobby of one of them or my old room in one of them turns up eerily

recognizable in a dream; the pasts of a number of speakeasies, diners, greasy

spoons, and drugstore lunch counters scattered all over the city that I knew

very well in the same period and that also have disappeared and that also turn

up in dreams; the pasts of a score or so of strange men and women—bohemians,

visionaries, obsessives, impostors, fanatics, lost souls, gypsy kings and gypsy

queens, and out-and-out freak-show freaks—whom I got to know and kept in touch

with for years while working as a newspaper reporter and whom I thought of back

then as being uniquely strange, only-one-of-a-kind-in-the-whole-world strange,

but whom, since almost everybody has come to seem strange to me, including

myself, I now think of, without taking a thing away from them, as being strange

all right, no doubt about that, but also as being stereotypes—as being

stereotypically strange, so to speak, or perhaps prototypically strange would

be more exact or archetypically strange or even ur-strange or maybe

old-fashioned pre-Freudian-insight strange would be about right, three good

examples of whom are (1) a bearded lady who was billed as Lady Olga and who

spent summers out on the road in circus sideshows and winters in a basement

sideshow on Forty-second Street called Hubert’s Museum, and who used to be

introduced to audiences by sideshow professors as having been born in a castle

in Potsdam, Germany, and being the half sister of a French duke but who I

learned to my astonishment when I first talked with her actually came from a

farm in a county in North Carolina six counties west of the county I come from

and who loved this farm and started longing to go back to it almost from the

moment she left it at the age of twenty-one to work in a circus but who made

her relatives uncomfortable when she went back for a visit (“ ‘How long

are you going to stay’ was always the first question they asked me,” she once

said) and who finally quit going back and from then on thought of herself as an

exile and spoke of herself as an exile (“Some people are exiled by the

government,” she would say, “and some are exiled by the po-lice or the F.B.I.

or the head of some old labor union or the Mafia or the Black Hand or the

K.K.K., but I was exiled by my own flesh and blood”), and who became a legend

in the sideshow world because of her imaginatively sarcastic and sometimes

imaginatively obscene and sometimes imaginatively brutal remarks about people

in sideshow audiences delivered deadpan and sotto voce to her fellow-freaks

grouped around her on the platform, and (2) a street preacher named James

Jefferson Davis Hall, who also came up here from the South and who lived in

what he called sackcloth-and-ashes poverty in a tenement off Ninth Avenue in

the Forties and who believed that God had given him the ability to read between

the lines in the Bible and who also believed that while doing so he had

discovered that the end of the world was soon to take place and who also

believed that he had been guided by God to make this discovery and who

furthermore believed that God had chosen him to go forth and let the people of

the world know what he had discovered or else supposing he kept this dreadful

knowledge to himself God would turn his back on him and in time to come he

would be judged as having committed the unforgivable sin and would burn in Hell

forever and who consequently trudged up and down the principal streets and

avenues of the city for a generation desperately crying out his message until

he wore himself out and who is dead and gone now and long dead and gone but

whose message remembered in the middle of the night (“It’s coming! Oh, it’s

coming!” he would cry out. “The end of the world is coming! Oh, yes! Any day

now! Any night now! Any hour now! Any minute now! Any second now!”) doesn’t

seem as improbable as it used to, and (3) an old Serbian gypsy woman named Mary

Miller—she called herself Madame Miller—whom I got to know with the help of an

old-enemy-become-old-friend of hers, a retired detective in the Pickpocket and

Confidence Squad, and whom I visited a number of times over a period of ten

years in a succession of her ofisas, or

fortune-telling parlors, and who was fascinating to me because she was always

smiling and gentle and serene, an unusually sweet-natured old woman, a good

mother, a good grandmother, a good great-grandmother, but who nevertheless had

a reputation among detectives in con-game squads in police departments in big

cities all over the country for the uncanny perceptiveness with which she could

pick out women of a narrowly specific kind—middle-aged, depressed, unstable,

and suggestible, and with access to a bank account, almost always a good-sized

savings bank account—from the general run of those who came to her to have

their fortunes told and for the mercilessness with which she could gradually

get hold of their money by performing a cruel old gypsy swindle on them, thehokkano baro, or the big trick; and, finally, not to

mention a good many other pasts, the past of New York City insofar as it is

connected directly or indirectly with my own past, and particularly the past of

the part of New York City that is known as lower Manhattan, the part that runs

from the Battery to the Brooklyn Bridge and that encompasses the Fulton Fish

Market and its environs, and which is part of the city that I look upon, if you

will forgive me for sounding so high-flown, as my spiritual home.

In my time, I have known quite a few of the worlds and the worlds within worlds of which New York City is made up, such as the world of the newspapers, the world of the criminal courts, the world of the museums, the world of the racetracks, the world of the tugboat fleets, the world of the old bookstores, the world of the old left-behind churches down in the financial district, the world of the old Irish saloons, the world of the old Staten Island oyster ports, the world of the party-boat piers at Sheepshead Bay, and the worlds of the city’s two great botanical gardens, the Botanical one in the Bronx and the Botanic one in Brooklyn. As a reporter and as a curiosity seeker and as an architecture buff and as a Sunday walker and later on as a member of committees in a variety of Save-this and Save-that and Friends-of-this and Friends-of-that organizations and eventually as one of the commissioners on the Landmarks Preservation Commission, I have known some of these worlds from the inside. Even so, I have never really felt altogether at home in any of them. And I have always felt at home in the Fulton Fish Market.

I know the exact day that I began living in the past. I didn’t know it then, of course, but I know it now. The day was October 4, 1968, a Friday. I had recently been in what I guess could be called a period of depression, during which, on the advice of a doctor, I had begun keeping a detailed diary, really a journal, and I have continued to keep it, so that I have a record of everything of any consequence that happened to me on that day and on almost every day of my life since then. On that day, according to my diary, a dream woke me up around 4 A.M. In this dream, I was standing on the muddy bank of a stream that I recognized, because of a peculiar old slammed-together split-rail bridge crossing it, as being the central stream running through Old Field Swamp, a cypress swamp near my home in North Carolina. I had often fished in this stream as a boy. In the dream, I was fishing for redfin pike with a snare hook hung from a line on the end of a reed pole. I was watching a sandbar in some shallow water out in the middle of the stream that the sun was shining on, and I was waiting for a pike to show up over the sandbar where it would be clearly visible and where I could maneuver my line until I had the hook under it and could snatch it out of the water. I was intent on what I was doing and oblivious to everything else. And then I happened to look up, and I saw that the bridge was on fire. And then I saw that the mud on the opposite bank was beginning to quiver and bubble and spit like lava and that smoke and flames were beginning to rise from it. And then, a few moments later, while I was standing there, staring, fish and alligators and snakes and muskrats and mud turtles and bullfrogs began floating down the stream, all belly up, and I realized that the central stream of Old Field Swamp had turned into one of the rivers of Hell. I dropped my pole and spun around and started running as hard as I could up a muddy path that led out of the swamp, but the mud on it was also beginning to quiver and bubble and spit, so I plunged into a briar patch beside the path and tried to fight my way through it, whereupon I woke up. I woke up with my heart in my mouth.

No comments:

Post a Comment