Many people probably think that the current spate of "Quiet Quitting" is something new. Or that "The Great Resignation" is a 2021 and 2022 phenomenon.

In the words of Hank Williams, Sr., "I've Been Down that Road Before." In fact, we all have.

Right at the start of our ongoing plague, the great historian Jon Meacham wrote an essay in "The Economist" magazine. I scanned it and saved it on my hard-drive, believing it was important, believing that Meacham's wisdom might one day come in handy.

As an aside, it doesn't matter how you define our current plagues. It could be coronavirus. It could be the plague of not believing in science. It could be the plague of lies. It could be the plague of fear. It could be the plague of an entire political party, now run on hate and lies. It could be 45-percent of our country believing in an abject liar and traitor. It doesn't matter what the plague is or where it came from, it only matters that it's with us and won't disappear for decades.

Here's the part of Meacham I think you should read and think about. Apologies for the length of the quote. Meacham has won a Pulitzer Prize and liberally quotes Barbara Tuchman, another Pulitzer winner. I ain't editing them.

"How did it end? For a long time it didn’t. There were numerous recurrences; scientists and historians still debate how the plague was brought under control. Some believe quarantine (the word derives from a 40-day period of confinement) and improved sanitation did the trick.

"The plague made no sense, and in making no sense, it helped reorder how human beings understood the world. The changes took time; as Tuchman remarked, 'The persistence of the normal is strong.'

"Yet the Black Death undermined received authority. The shift from faith in institutions — monarchies, aristocracies, papacies — to an emphasis on the individual would be accelerated in the years of the Protestant Reformation and the scientific revolution, but Tuchman posited that the roots of modernity can be traced to the disease-bearing fleas and rats of the 14th century.

"'Survivors of the plague, finding themselves neither destroyed nor improved, could discover no Divine purpose in the pain they had suffered,' Tuchman wrote. 'God’s purposes were usually mysterious, but this scourge had been too terrible to be accepted without questioning. If a disaster of such magnitude, the most lethal ever known, was a mere wanton act of God or perhaps not God’s work at all, then the absolutes of a fixed order were loosed from their moorings. Minds that opened to admit these questions could never again be shut. Once people envisioned the possibility of change in a fixed order, the end of an age of submission came into sight; the turn to individual conscience lay ahead. To that extent the Black Death may have been the unrecognized beginning of modern man.'"

But back to Quiet Quitting and the Great Resignation.

Both those terms are coined by the people and the systems that want to keep the old order intact.

The Great Resignation could just as easily, and from labor's point of view, not capital's, be called the "Great Betrayal." The supporters of runaway Capitalism and the press don't like the old order of complacent workers obeying their masters being upset. The nomenclatura "great resignation," implies, intentionally, that workers are lazy and slovenly and in the wrong.

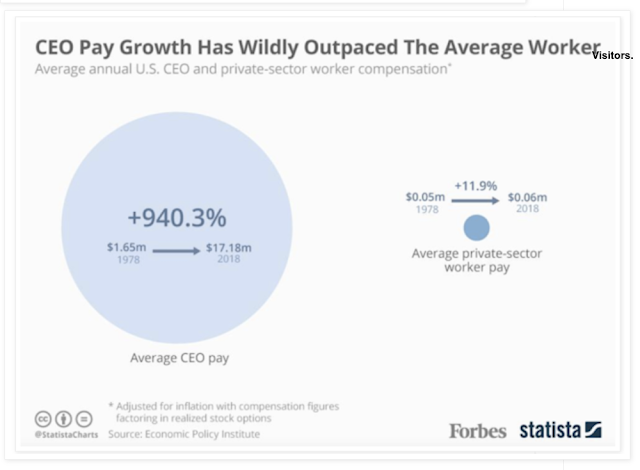

I call it the Great Betrayal because as the masters of capital have gotten richer and richer, the workers have gotten a whole lot of less. Less money. Less security. Less control (most jobs are under oligopoly control.) And less humanity. These two charts might illuminate what I mean.

Similarly, the equally-manipulative term "Quiet Quitting," which I prefer to flip and call "Quiet Stealing." In my last agency job, I routinely worked about sixty-hours-a-week while being paid for just thirty-seven-and-a-half.

All that has been stripped away today, yet the expectation that you work "executive hours," has been bolstered. Companies are getting rich, and people are "Quiet Quitting" because so many people are coerced to give free labor.

Don't take it from me, here is Stanford professor, and author of "The Great Leveler," Walter Scheidel talking about the Great Plague.

"According to Agnolo di Tura of Siena, 'so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.'

"And yet this was only the beginning. The plague returned a mere decade later and periodic flare-ups continued for a century and a half, thinning out several generations in a row. Because of this 'destructive plague which devastated nations and caused populations to vanish,' the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun wrote, 'the entire inhabited world changed.'

"'The wealthy found some of these changes alarming.' In the

words of an anonymous English chronicler, 'Such a shortage of laborers ensued

that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be

persuaded to serve the eminent for triple wages.' Influential employers, such

as large landowners, lobbied the English crown to pass the

Ordinance of Laborers, which informed workers that they were 'obliged to accept

the employment offered' for the same measly wages as before.

"But as successive waves of plague shrank the work force, hired hands and tenants 'took no notice of the king’s command,' as the Augustinian clergyman Henry Knighton complained. 'If anyone wanted to hire them he had to submit to their demands, for either his fruit and standing corn would be lost or he had to pander to the arrogance and greed of the workers.'

"Looking at the historical record across Europe during the late Middle Ages, we see that elites did not readily cede ground, even under extreme pressure after a pandemic. During the Great Rising of England’s peasants in 1381, workers demanded, among other things, the right to freely negotiate labor contracts. Nobles and their armed levies put down the revolt by force, in an attempt to coerce people to defer to the old order. But the last vestiges of feudal obligations soon faded. Workers could hold out for better wages, and landlords and employers broke ranks with one another to compete for scarce labor."

The Great Resignation and Quiet Quitting, whatever you want to call them, might each be a tempest in a teapot, a small trend blown out of proportion by the 27-hour-a-day news cycle. Or they could be a genuine subversion to the old order.

No comments:

Post a Comment