When I was still just 17 and playing under the unforgiving sun in the Mexican Baseball League, for one of the first times in my life I learned what it felt like to feel loved.

My manager, Hector Quetzacoatl Padilla, which my yanqui tongue pronounced Hector Quesadilla saw something in me that I, of course, I hadn't even seen myself.

A few years earlier, Mrs. Chapin, my tenth-grade English teacher acted on a similar impulse. While most of my classmates were assigned one book to read every two weeks or so, Mrs. Chapin would send me home with six books, or eight.

The class was assigned "The Emperor Jones," by Eugene O'Neill. Mrs. Chapin also weighted me down with "Mourning Becomes Elektra," "A Long Day's Journey into Night," and a passel of other plays I could scarcely fathom.

Years later when I started working as a copywriter at a major New York agency, I went through that sort of boot camp again. When I gave my boss, Harold, some copy to review he would schedule an hour or two--as long as it took--and go through every word of my copy with me. He wanted to know my reasons for every word choice I had made. Harold wanted to know I was thinking everything through.

One day back in Saltillo, Hector and Guillermo Sisto, the oldest player on the team and Hector's best-friend and extra-player-coach took me aside.

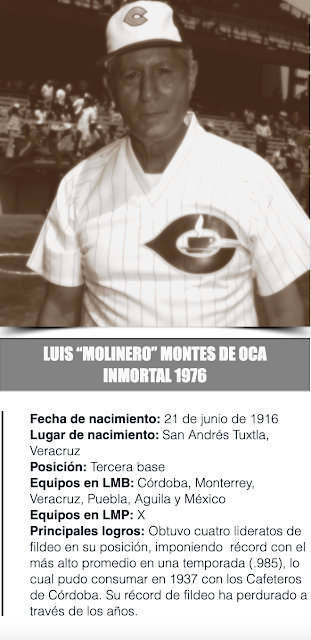

"You have heard of Luis Montes de Oca?" Sisto asked me. "Two coaches would help him with his fielding. One would fungo from the right side. One from the left."

"We do this for you. You have manos de piedra. Hands of stone. We will soften them."

"I have not heard of Luis Montes de Oca," I conceded.

"Un mago. A magician. Houdini."

Sisto and Hector stationed themselves by the pitcher's mound, each with a bucket of balls. Sisto batting left, Hector right. And one after another like an old Soviet Katyusha rocket launcher they shot balls at me.

One then another then another. Crack, thud. Crack, thud. Crack, thud.

What seemed like 50 grounders a minute came my way. 25 from Sisto. 25 from Hector.

I'd smack each ball with my glove, slap it to the ground, then shift to smack another.

Some hit my shoulders, or bounced off my chest. Some I dove for, some, I missed. But they kept coming like a hail storm.

When the buckets of balls were emptied, the three of us gathered up the balls and we went at it again. I had been to a thousand baseball practices in my life and fielded what seemed like a million grounders smacked my way. I had endured a stretch of 14 games in twelve days. 12-hour bus rides up over the Sierras through the night. And game after game in hundred-degree heat.

But I never felt as beaten as I felt after those hours of double-barreled duress. It was like being in the middle of a beehive and trying to swat yourself safe. Except the bees were like Medusa and if you swatted a dozen, a dozen-dozen more would arrive.

"We go again," Hector said after another hundred or two-hundred grounders. "We go again."

"No," said Sisto. "We have done enough. We have hit our bodies tired. We have done enough.

I walked alone off the field to the showers. My body had aches where I never knew before I even had body. Bending over to untie my spikes was like climbing a steep hill.

"It is good," Hector told me.

"It made de Oca, de Oca," Sisto said.

I cried to myself as I showered and dressed. I inspected the red, blue and purple welts all over my body. We had a game that night. I was as sore as a bad welterweight and I could barely lift my hands above my waist.

The hands of stone weigh heavy.

No comments:

Post a Comment