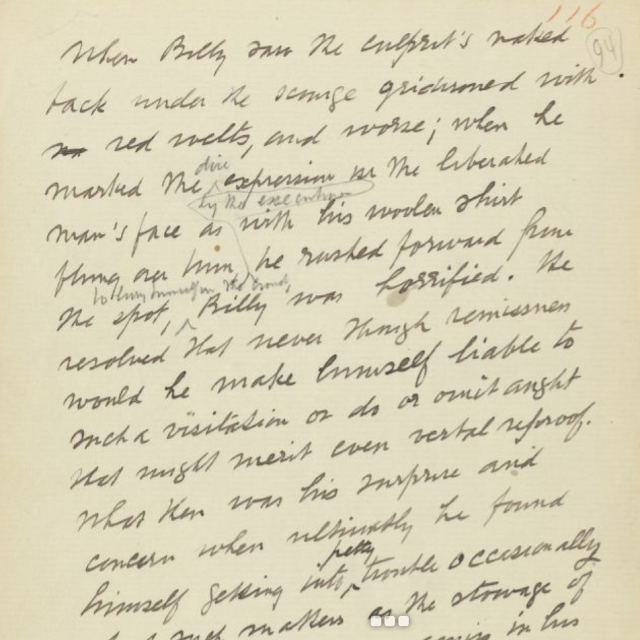

in a breadbox belonging to Melville's granddaughter.

For about as long as I've been in the advertising business, or--better--the consciousness business, I've been something of a solo act.

It's not that I don't like people, I do.

It's not that I don't trust people, I do.

It's not that I'm a loner, I'm not.

It's just that for as long as I've lived I've trusted attained wisdom more than received wisdom.

That's a fancy way of saying I'd rather find something out for myself than be told what to do.

Maybe that comes from having had a fairly strict academic background. I started out wanting to be a college professor. And while I am 43-years deep into my advertising career, I've never fully given up on my original aspirations.

When I was doing scholarly research, I was searching for truths myself. I didn't have someone telling me what they thought the white whale meant and turning their thoughts over to me for stylistic rendering. You learn more and you think more and you delve more when you do your own thinking.

Further, you learn more when you're forced to explain your own thinking. Vocalization uncovers shortcomings or logic gaps. When you talk things through, you have time to think them through and make them better.

For most of my career, I've dealt with something I've only recently voiced. I didn't have, until about five years ago, the confidence to say this aloud.

Most briefs are what I call "dump-truck briefs."

A veritable dump-truck-full of charged ions of information spinning around the nucleus of a brand.

Dump-truck briefs are the best kind of briefs.

Not the simplest, but the best kind. Because they are the most demanding kind of briefs.

They demand the deepest sort of thinking, the soakiest-immersion and the widest canvas. They don't tell you in answer, they give you reams of information that good creatives will combine with their knowledge of human behaviors and the human condition to find a connection. To find a truth as to how a brand helps a person.

Somehow in our modern advertising world, we have decided that getting to an executable brief is too difficult for copywriters and art directors. In fact, the best copywriters and art directors, the best creatives in any field from physics to flatulence are people who never accept easy answers and never stop looking for the hidden.

I heard Steven Heller the designer once in a conversation with Milton Glaser. Heller repeated the common statement that "less is more." Glaser sat back in his chair.

"I've heard that all my life," Glaser said. "And I don't believe it. If you go home tonight and you have a Persian carpet, or a Kelim, or something elaborate, sometimes more is more. They're complex. They force you to look and make connections. Sometimes less is more. Sometimes more is more. Sometimes more is enough."

I listened to a 36-minute interview the other day with Tony Brignull, the most-awarded English copywriter ever. He was talking about Collett Dickenson Pearce (CDP) perhaps the best English ad agency ever.

Tony said, for the first two weeks after getting a brief, just about every agency was as good as CDP. After two weeks, however, no agency was better than CDP. CDP kept thinking.

More is more.

That's the thing about most processes of discovery. I'd bet in physics a hundred people got 90-percent as far as Einstein. In baseball, a lot of hits get 90-percent of the way to hitting a double. And a lot of relationships get 90-percent of the way to being long-lasting and powerful.

But it's the work that's done after the work is done that is the most important work. The thinking you think after everyone else is done thinking.

When I worked in agencies, it was usual for me to count planners as my best friends and closest confidants. They're usually the people I run my earliest thoughts, scribbles and ideas by.

To my mind it makes no sense to separate creative people from reading and fact-finding and, mostly, digging. It makes no sense to have creatives who are more stylists than diggers.

Of course, epiphanies can strike like lightning. Most often though, epiphanies, like ditches, canals and tunnels come from digging. I think you have to break a lot of crayons to draw a picture--even a child knows that. You have to bang a lot of keys to write a sentence. You can get help along the way: planners, partners, account, clients.

But it's up to you to keep working.

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night and think about an assignment I had in the 80s or the 90s that I did a good job on. Maybe won an award for.

It comes to me that if I had re-written what I did this way or that, it might have been better.

That's not merely neurosis.

That's a ballplayer thinking how this at bat can make his next at bat better. It's keeping a 'book' on everything you do so you can try to improve.

Even if you don't make your current work better, you might make your next assignment better.

As Dylan Thomas wrote, that's "the force that through the green fuse drives the flower."

Someday, we'll figure out what that, and everything else, means. Or we won't.

No comments:

Post a Comment