My mother was not a nice woman. And she was a horrible mother. She was mean, abusive, borderline, demanding and never once in the seventeen or so years I lived under her teetering roof did she hand me a compliment that she didn't take quickly take-away with her other hand.

However, she gave me some things that today--almost fifty years after I left her tilted little home for the last time--that I am thankful for.

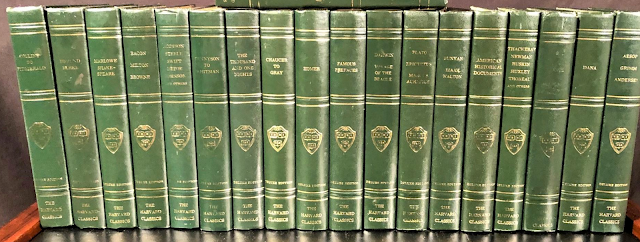

Of course, her house, such as it was, was filled with books. No matter what books were in her stuffed-to-the-gunwales shelves, we were expected to absorb their contents. From the films of Greta Garbo to the Harvard Classics--all 50 volumes in their beautiful olive drab linen covers.

There could be a quiz at any moment--and the consequences of any intimations of stupidity were not what would be considered acceptable today. The stories I read of English boys' schools, from Thomas Hughes' "Tom Brown's Schooldays," or something by Dickens, or even old Shirley Temple movies where she was forced to shovel coal and sleep in a freezing attic told of disciplines and regimens far less strict than those my brother and I grew up under.

In fact, we lived under a rigid system of demerits (there were no rewards) and if we accumulated enough of them, we could be put on report. Usually that meant isolation in the damp and mousy basement where we had to pick up years of detritus and every tie-up in parcels approximately every issue of National Geographic ever published. Somehow my younger sister, Nancy, escaped this torment, though she got more than her share of maternal mishigoss.

My mother also beat me into becoming a bit of a scullery maid or even a scullion. She trained me to the point of excellence at the most grueling and labor-intensive of the culinary arts. To this day, I can peel apples and potatoes like I'd spent a lifetime as a buck private in the army and passed my time in uniform not fighting enemies but up to my calloused elbows in KP. In a John Henry vs. Steam Hammer-type match against a Cuisinart, I'd advise you put your drachma on yours truly. It's not likely any mere machine can best me.

When I think about the rigor I grew up under, it's easy for me to PTSD myself into a psychiatrist-endorsed gloom. It was a helluva upbringing I had. And I have the scars to prove it.

But, on the other hand, when the phone rings and a month of work for three teams is due in three days, I know I can handle it. It's just a heap of potatoes that need peeling.

When a client gives feedback like, "Can you make it ownable without being distinctive," I don't worry. I attack that oxymoron and tackle it like gutters that needed cleaning during a rainstorm or a long parquet hallway that needed to be buffed to a I-can-see-myself-sheen.

When I'm told two agencies before me tried and failed and now I have two days, I welcome the challenge and amn't afraid of it. I've been down that road before and have had a lifetime of worser assignments with more dire consequences for failure.

The final thing my harridan of a mother bestowed upon me was something of a sense of humor. Humor became my coping mechanism and my greatest resource.

And while I have a slate of wife-jokes that might have made Henny Youngman jealous, my mom jokes are even more numerous.

Like this one, which I'll end with.

My mother adopted a highway. After two weeks it went looking for its birth highway.

No comments:

Post a Comment