There are a few people who have known me a long time and who don't hate me or who aren't bored by me.

Some of them I know in real life. More, it seems, know me from postings like this one, or through some connection we've made online. Like a nebula meeting a mist of ether.

For whatever reason or reasons, they tolerate my many quirks and my even more numerous mania. I say mania, because like many people who consider themselves a 'sort-of-writer,' I can get intensely focused on things that seem important, valuable, or worth-noting only to myself. These are the things I come back to week after week, month after month, and yes, decade after decade. Idee fixe, the frogs might croak.

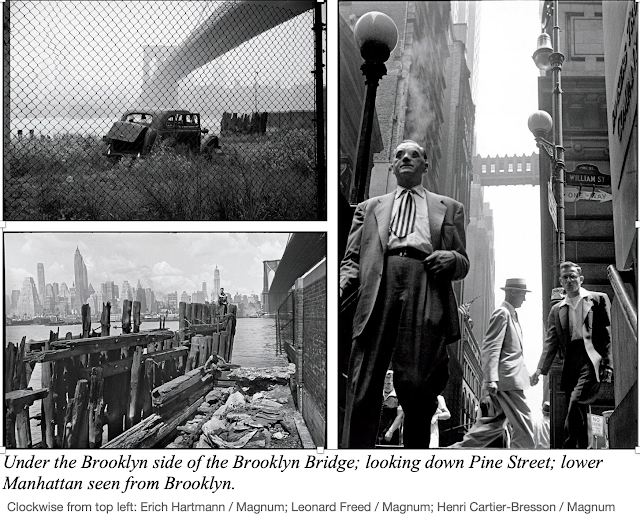

Of late, New York, my one and only home, the Castor to my Pollux, the Damon to my Pythias, the Hero to my Leander, has taken a beating. There was a mass-shooting on the subway earlier this week. And attractive news-readers can be seen flapping their botox-ed lips about the myriad dangers of the city. It's a pre-apocalyptic end-of-the-world narrative. Those usually arrive during periods of massive change--like the one we're living through now, or say ancient Rome during the rise of Christianity.

My guess is, like a lot of data, the perils of Gotham are driven more by a narrative than reality. I was uptown, downtown, all around the town for the last ten days. Attending a memorial service held at Columbia University, down on MacDougal for an old-ad-peoples' periodic dinner, and walking around dogwood- blossoming Central Park, where everyone's individual beauty is only bettered by their even-more-beautiful dogs.

For about forty years, I've been telling people to read Joseph Mitchell. If you want to read spare, elegant, empathic writing read Joseph Mitchell. If you want to learn to be better, read someone better than you.

Mitchell came to New York in the 1930s and lived here until he died in 1996. He worked and wrote at "The New Yorker" for most of those years--and as Oedipus loved his mother, he loved this cursed set of islands in a stream--and the Bronx as well, which is the only one of New York's five boroughs that's not an island.

Below is four minutes of Mitchell.

I can't think of a better way to spend a moment cherishing the glory of the world and of life itself, no matter how awful it is.

As always, thank you for reading. Thank you for sharing. Thank you for doing your bit to make the world a little richer.

What I really like to do is wander aimlessly in the city. I like to walk the streets by day and by night. It is more than a liking, a simple liking—it is an aberration. Every so often, for example, around nine in the morning, I climb out of the subway and head toward the office building in midtown Manhattan in which I work, but on the way a change takes place in me—in effect, I lose my sense of responsibility—and when I reach the entrance to the building I walk right on past it, as if I had never seen it before. I keep on walking, sometimes for only a couple of hours but sometimes until deep in the afternoon, and I often wind up a considerable distance away from midtown Manhattan—up in the Bronx Terminal Market maybe, or over on some tumbledown old sugar dock on the Brooklyn riverfront, or out in the weediest part of some weedy old cemetery in Queens. It is never very hard for me to think up an excuse that justifies me in behaving this way (I have a great deal of experience in justifying myself to myself)—a headache that won’t let up is a good enough excuse, and an unusually bleak and overcast day is as good an excuse as an unusually balmy and springlike day. Or it might be some horrifying or unnerving or humiliating thought that came into my mind while I was lying awake in the middle of the night and that keeps coming back—some thought about the swiftness of time in its flight, for example, or about old age itself, or about death in general and death in particular, or about the possibility (which is far more horrifying to me than the possibility of a nuclear war) that after death many of us may find out (and quite rudely, too, as a friend of mine who was lying on his deathbed in a hospital at the time once remarked) that the eternal and everlasting flames of Hell actually exist.

We would all be better off with a little less quotidian bullshit and a little more Joseph Mitchell.

Bibliography[edit]

Collections from prior newspaper works[edit]

- My ears are bent. Vintage Books. 1938. ISBN 978-0375726309.

- McSorley's Wonderful Saloon. Pantheon Books. 1943. ISBN 978-0375421020.

Collections of work from The New Yorker[edit]

- Old Mr. Flood. MacAdam/Cage. 1948. ISBN 978-1596921146.

- The Bottom of the Harbor. Pantheon Books. 1959. ISBN 978-0375714863.

- Joe Gould's Secret. Modern Library. 1965. ISBN 978-0679601845.

- Up In The Old Hotel and Other Stories. Pantheon Books. 1992. ISBN 978-0679412632.[35])

All works from The New Yorker[edit]

1931–1939[edit]

- Comment With E.B. White Comment (January 16, 1931)

- Comment With E.B. White Comment (August 12, 1932)

- High Hats' Harold D. Winney & Joseph Mitchell The Talk of the Town (June 9, 1933)

- Reporter at Large They Got Married in Elkton A Reporter at Large (November 3, 1933)

- Home Girl Profiles (February 23, 1934)

- Reporter at Large. Bar and Grill. A Reporter at Large (November 13, 1936)

- Mr. Grover A. Whalen and the Midway A Reporter at Large (June 25, 1937)

- The Kind Old Blonde Fiction (May 27, 1938)

- Reporter at Large A Reporter at Large (August 19, 1938)

- Mrs. Bright and Shining Star Chibby Fiction (October 28, 1938)

- I Couldn't Dope it Out Fiction (December 2, 1938)

- Christmas Story A Reporter at Large (December 16, 1938)

- Obituary of a Gin Mill A Reporter at Large (December 30, 1938)

- Downfall of Fascism in Black Ankle County Fiction (January 6, 1939)

- The Little Brutes! A Reporter at Large (February 3, 1939)

- Dignity. The Talk of the Town (February 10, 1939)

- All You Can Hold For Five Bucks. A Reporter at Large (April 7, 1939)

- Plans The Talk of the Town (April 14, 1939)

- Hotfoot The Talk of the Town (April 21, 1939)

- The Catholic Street A Reporter at Large (April 21, 1939)

- Houdini's Picnic A Reporter at Large (April 28, 1939)

- More Plans The Talk of the Town (April 28, 1939)

- Uncle Dockery and the Independent Bull Fiction (May 5, 1939)

- Windsor's Friends With Russell Maloney The Talk of the Town (May 19, 1939)

- The Hospital Was All Right Fiction (May 19, 1939)

- A Mess of Clams A Reporter at Large (July 21, 1939)

- Goodbye, Shirley Temple Fiction (September 8, 1939)

- Mr. Barbee's Terrapin A Reporter at Large (October 20, 1939)

- The Markee Profiles (October 27, 1939)

- Sunday Night Was a Dangerous Night Fiction (November 24, 1939)

1940–1949[edit]

- I Blame it All on Mamma Fiction (January 5, 1940)

- Santa Claus Smith of Riga, Latvia, Europe A Reporter at Large (March 22, 1940)

- The Old House at Home Profiles (April 14, 1940)

- Lady Olga Profiles (July 26, 1940)

- Evening with a Gifted Child A Reporter at Large (August 23, 1940)

- Second-Hand Hot Spots Profiles (September 13, 1940)

- Mazie Profiles (December 14, 1940)

- New Resident. With Eugene Kinkead & Harold Ross The Talk of the Town (January 24, 1941)

- Mr. Colborne's Profanity-Exterminators Profiles (April 25, 1941)

- But There is No Sound A Reporter at Large (September 12, 1941)

- The Tooth Profiles (October 24, 1941)

- King of the Gypsies Profiles (August 7, 1942)

- Professor Sea Gull Profiles (December 4, 1942)

- Comment Comment (April 23, 1943)

- A Spism and a Spasm Profiles (July 16, 1943)

- The Mayor of the Fish Market Profiles (December 24, 1943)

- Rebate. With F. Whitz The Talk of the Town (February 25, 1944)

- Thirty-Two Rats from Casablanca A Reporter at Large (April 21, 1944)

- Coffins! Undertakers! Hearses! Funeral Parlors! A Reporter at Large (November 17, 1944)

- Solution. (March 2, 1945)

- Mr. Flood's Party A Reporter at Large (July 27, 1945)

- Dragger Captain. Profiles (December 27, 1946)

- Dragger Captain: Professors Abroad Profiles (January 3, 1947)

- Incidental Intelligence With Brendan Gill The Talk of the Town (August 15, 1947)

- The Mohawks in High Steel A Reporter at Large (September 9, 1949)

1950–1964[edit]

- The Bottom of the Harbor Profiles (December 29, 1950)

- The Cave Profiles (June 20, 1952)

- Comment With Brendan Gill Comment (May 6, 1955)

- The Beautiful Flower Profiles (May 27, 1955)

- Three Men With Brendan Gill The Talk of the Town (April 20, 1956)

- Mr. Hunter's Grave Profiles (September 14, 1956)

- Observer With John McCarten The Talk of the Town (November 14, 1958)

- The Rivermen Profiles (March 27, 1959)

- Joe Gould's Secret - I Profiles (September 11, 1964)

- Joe Gould's Secret Profiles (September 18, 1964)

2000–2015[edit]

- Takes Takes (May 28, 2000)

- Street Life Personal History (February 3, 2013)

- Days in the Branch Personal History (November 24, 2014

A Place of Pasts Personal History (February 9, 2015) The Cave

How Louis Morino, the wise man of seafood, runs his restaurant.

June 20, 1952

Every now and then, seeking to rid my mind of thoughts of death and doom, I get up early and go down to Fulton Fish Market. I usually arrive around five-thirty, and take a walk through the two huge open-fronted market sheds, the Old Market and the New Market, whose fronts rest on South Street and whose backs rest on piles in the East River. At that time, a little while before the trading begins, the stands in the sheds are heaped high and spilling over with forty to sixty kinds of finfish and shellfish from the East Coast, the West Coast, the Gulf Coast, and half a dozen foreign countries. The smoky riverbank dawn, the racket the fishmongers make, the seaweedy smell, and the sight of this plentifulness always give me a feeling of well-being, and sometimes they elate me. I wander among the stands for an hour or so. Then I go into a cheerful market restaurant named Sloppy Louie’s and eat a big, inexpensive, invigorating breakfast—a kippered herring and scrambled eggs, or a shad-roe omelet, or split sea scallops and bacon, or some other breakfast specialty of the place.

Sloppy Louie’s occupies the ground floor of an old building at 92 South Street, diagonally across the street from the sheds. This building faces the river and looks out on the slip between the Fulton Street fish pier and the old Porto Rico Line dock. It is six floors high, and it has two windows to the floor. Like the majority of the older buildings in the market district, it is made of hand-molded Hudson River brick, a rosy-pink and relatively narrow kind that used to be turned out in Haverstraw and other kiln towns on the Hudson and sent down to the city in barges. It has an ornamented tin cornice and a slate-covered mansard roof. It is one of those handsome, symmetrical old East River waterfront buildings that have been allowed to dilapidate. The windows of its four upper floors have been boarded over for many years, a rain pipe that runs down the front of it is riddled with rust holes and there are gaps here and there on its mansard where slates have slipped off. In the afternoons, after two or three, when the trading is over and the stands begin to close, the slimy, overfed gulls that scavenge in the market roost by the hundreds along its cornice, hunched up and gazing downward.

I have been going to Sloppy Louie’s for nine or ten years, and the proprietor and I are old friends. His name is Louis Morino, and he is a contemplative and generous and worldly-wise man in his middle sixties. Louie is a North Italian. He was born in Recco, a fishing and bathing-beach village thirteen miles southeast of Genoa, on the Eastern Riviera. Recco is ancient; it dates back to the third century. Families in Genoa and Milan and Turin own villas in and around it, and go there in the summer. Some seasons, a few English and Americans show up. According to a row of colored-postcard views of it Scotch-taped to a mirror on the wall in back of Louie’s cash register, it is a village of steep streets and tall, square, whitewashed stone houses. The fronts of the houses are decorated with stencilled designs—madonnas, angels, flowers, fruit, and fish. The fish design is believed to protect against the evil eye and appears most often over doors and windows. Big, lush fig bushes grow in almost every yard. In the center of the village is an open-air market where fishermen and farmers sell their produce off plank-and-sawhorse counters. Louie’s father was a fisherman. His name was Giuseppe Morino, and he was called, in Genoese dialect, Beppe du Russu, or Joe the Redhead. “My family was one of the old fishing families in Recco that the priest used to tell us had been fishing along that coast since Roman times,” Louie says. “We lived on a street named the Vico Saporito that was paved with broken-up sea shells and wound in and out and led down to the water. My father did a kind of fishing that’s called haul-seining over here, and he set lobster traps and jigged for squid and bobbed for octopuses. When the weather was right, he used to row out to an underwater cave he knew about and anchor over it and take a bob consisting of some scraps of raw beef tied to a line with a stone on the end of it and drop it in the mouth of the cave, and the octopuses would shoot up out of the dark down there and swallow the beef scraps and that would hold them on the line, and then my father would draw the bob up slow and steady and pull the octopuses loose from the beef scraps one by one and toss them in a tub in the boat. He’d bob up enough octopuses in a couple of hours to glut the market in Recco. This cave was full of octopuses; it was choked with them. He had found it, and he had the rights to it. The other fishermen didn’t go near it; they called it Beppe du Russu’s cave. In addition to fishing, he kept a rickety old bathhouse on the beach for the summer people. It stood on stilts, and I judge it had fifty to sixty rooms. We called it the Bagni Margherita. My mother ran a little buffet in connection with it.” Louie left Recco in 1905, when he was close to eighteen. “I loved my family,” he says, “and it tore me in two to leave, but I had five brothers and two sisters, and all my brothers were younger than me, and there were already too many fishermen in Recco, and the bathhouse brought in just so much, and I had a fear kept persisting there might not be enough at home to go around in time to come, so I got passage from Genoa to New York scrubbing pots in the galley of a steamship and went straight from the dock to a chophouse on East 138th Street in the Bronx that was operated by a man named Capurro who came from Recco. Capurro knew my father when they both were boys.” Capurro gave Louie a job washing dishes and taught him how to wait on tables. He stayed there two years. For the next twenty-three years, he worked as a waiter in restaurants all over Manhattan and Brooklyn. He has forgotten how many he worked in; he can recall the names of thirteen. Most of them were medium-size restaurants of the Steak-&-Chops, We-Specialize-in-Seafood type. In the winter of 1930, he decided to risk his savings and become his own boss. “At that time,” he says, “the stock-market crash had shook everything up and the depression was setting in, and I knew of several restaurants in midtown that could be bought at a bargain—lease, furnishings, and good will. All were up-to-date places. Then I ran into a waiter I used to work with and he told me about this old rundown restaurant in an old run-down building in the fish market that was for sale, and I went and saw it, and I took it. The reason I did, Fulton Fish Market reminds me of Recco. There’s a world of difference between them. At the same time, they’re very much alike—the fish smell, the general gone-to-pot look, the trading that goes on in the streets, the roofs over the sidewalks, the cats in corners gnawing on fish heads, the gulls in the gutters, the way everybody’s on to everybody else, the quarrelling and the arguing. There’s a boss fishmonger down here, a spry old hard-headed Italian man who’s got a million dollars in the bank and dresses like he’s on relief and walks up and down the fish pier snatching fish out of barrels by their tails and weighing them in his hands and figuring out in his mind to a fraction of a fraction how much they’re worth and shouting and singing and enjoying life, and the face on him, the way he conducts himself, he reminds me so much of my father that sometimes, when I see him, it puts me in a good humor, and sometimes it breaks my heart.”

Louie is five feet six, and stocky. He has an owl-like face—his nose is hooked, his eyebrows are tufted, and his eyes are large and brown and observant. He is white-haired. His complexion is reddish, and his face and the backs of his hands are speckled with freckles and liver spots. He wears glasses with flesh-colored frames. He is bandy-legged, and he carries his left shoulder lower than his right and walks with a shuffling, head-up, old-waiter’s walk. He dresses neatly. He has his suits made by a high-priced tailor in the insurance district, which adjoins the fish-market district. Starting work in the morning, he always puts on a fresh apron and a fresh brown linen jacket. He keeps a napkin folded over his left arm even when he is standing behind the cash register. He is a proud man, and somewhat stiff and formal by nature, but he unbends easily and he has great curiosity and he knows how to get along with people. During rush hours, he jokes and laughs with his customers and recommends his daily specials in extravagant terms and listens to fish-market gossip and passes it on; afterward, in repose, having a cup of coffee by himself at a table in the rear, he is grave. Louie is a widower. His wife, Mrs. Victoria Piazza Morino, came from a village named Ruta that is only two and a half miles from Recco, but he first became acquainted with her in Brooklyn. They were married in 1928, and he was deeply devoted to her. She died in 1949. He has two daughters—Jacqueline, who is twenty-two and was recently graduated from the Mills College of Education, a school for nursery, kindergarten, and primary teachers on lower Fifth Avenue, and Lois, who is seventeen and was recently graduated from Fontbonne Hall, a high school on Shore Road in Brooklyn that is operated by the Sisters of St. Joseph. They are smart, bright, slim, vivid, dark-eyed girls. Louie has to be on hand in his restaurant in the early morning, and he usually gets up between four and five, but before leaving home he always squeezes orange juice and puts coffee on the stove for his daughters. Most days, he gets home before they do and cooks dinner. Louie owns his home, a two-story brick house on a maple-bordered street in the predominantly Norwegian part of the Bay Ridge neighborhood in Brooklyn. There is a saying in Recco that people and fig bushes do best close to salt water; Louie’s home is only a few blocks from the Narrows, and fifteen years ago he ordered three tiny fig bushes from a nursery in Virginia and set them out in his back yard, and they have flourished. In the late fall, he wraps an accumulation of worn-out suits and dresses and sweaters and sheets and blankets around their trunks and limbs. “All winter,” he says, “when I look out the back window, it looks like I got three mummies stood up out there.” At the first sign of spring, he takes the wrappings off. The bushes begin to bear the middle of July and bear abundantly during August. One bush bears small white figs, and the others bear plump black figs that split their skins down one side as they ripen and gape open and show their pink and violet flesh. Louie likes to gather the figs around dusk, when they are still warm from the heat of the day. Sometimes, bending beside a bush, he plunges his face into the leaves and breathes in the musky smell of the ripening figs, a smell that fills his mind with memories of Recco in midsummer.

Louie doesn’t think much of the name of his restaurant. It is an old restaurant with old furnishings that has had a succession of proprietors and a succession of names. Under the proprietor preceding Louie, John Barbagelata, it was named the Fulton Restaurant, and was sometimes called Sloppy John’s. When Louie took it over, he changed the name to Louie’s Restaurant. One of the fishmongers promptly started calling it Sloppy Louie’s, and Louie made a mistake and remonstrated with him. He remonstrated with him on several occasions. As soon as the people in the market caught on to the fact that the name offended Louie, naturally most of them began using it. They got in the habit of using it. Louie brooded about the matter off and on for over three years, and then had a new swinging signboard erected above his door with sloppy louie’s restaurant on it in big red letters. He even changed his listing in the telephone book. “I couldn’t beat them,” he says, “so I joined them.”

Sloppy Louie’s is small and busy. It can seat eighty, and it crowds up and thins out six or seven times a day. It opens at five in the morning and closes at eight-thirty in the evening. It has a double door in front with a show window on each side. In one window are three sailing-ship models in whiskey bottles, a giant lobster claw with eyes and a mouth painted on it, a bulky oyster shell, and a small skull. Beside the shell is a card on which Louie has neatly written, “Shell of an Oyster dredged from the bottom of Great South Bay. Weighed two and a quarter pounds. Estimated to be fifteen years old. Said to be largest ever dredged in G. S. B.” Beside the skull is a similar card, which says, “This is the skull of a Porpoise taken by a dragger off Long Beach, Long Island.” In the other window is an old pie cupboard with glass sides. To the left, as you enter, is a combined cigar showcase and cashier’s desk, and an iron safe with a cash register on top of it. There are mirrors all around the walls. Four lamps and three electric fans with wooden blades that resemble propellers hang from the stamped-tin ceiling. The tables in Louie’s are communal, and there are exactly one dozen; six jut out from the wall on one side of the room and six jut out from the wall on the other side, and a broad aisle divides them. They are long tables, and solid and old and plain and built to last. They are made of black walnut; Louie once repaired a leg on one, and said it was like driving a nail in iron. Their tops have been seasoned by drippings and spillings from thousands upon thousands of platters of broiled fish, and their edges have been scratched and scarred by the hatchets and bale hooks that hang from frogs on fishmongers’ belts. They are identical in size; some seat six, and some have a chair on the aisle end and seat seven. At the back of the room, hiding the door to the kitchen, is a huge floor mirror on which, each morning, using a piece of moistened chalk, Louie writes the menu for the day. It is sometimes a lengthy menu. A good many dishes are served in Louie’s that are rarely served in other restaurants. One day, interspersed among the staple seafood-restaurant dishes, Louie listed cod cheeks, salmon cheeks, cod tongues, sturgeon liver, blue-shark steak, tuna steak, squid stew, and seven kinds of roe—shad roe, cod roe, sturgeon roe, lemon-sole roe, mackerel roe, herring roe, and yellow-pike roe. Cheeks are delectable morsels of flesh found along the jaws of some fishes. They come into the market in small shipments, and the fishmongers, thinking of their own gullets, let Louie buy almost every shipment. Recently, a large shipment of salmon cheeks—two hundred and seventy pounds—came in from the West Coast, and Louie bought it and put it in his deep freeze. The fishmongers use Louie’s as a testing kitchen. When anything unusual is shipped to the market, it is taken to Louie’s and tried out. In the course of a year, Louie’s undoubtedly serves a wider variety of seafood than any other restaurant in the country.

When I go to Sloppy Louie’s for breakfast, I always try to get a chair at one of the tables up front, and Louie generally comes out from behind the cash register and tells me what is best to order. Some mornings, if there is a lull in the breakfast rush, he draws himself a cup of coffee and sits down with me. One morning a while back, he sat down, and I asked him how things were going, and he said he couldn’t complain, he had about as much business as he could handle. “My breakfast trade still consists almost entirely of fishmongers and fish buyers,” he said, “but my lunch trade has undergone a change. The last few years, a good many people in the districts up above the market have taken to walking down here occasionally for lunch—people from the insurance district, the financial district, and the coffee-roasting district. Some days, from noon to three, they outnumber the fishmongers. I hadn’t realized myself how great a change had took place until just the other day I happened to notice the mixed-up nature of a group of people sitting around one table. They were talking back and forth, the way people do in here that never even saw each other before, and passing the ketchup, and I’ll tell you who they were. Sitting on one side was an insurance broker from Maiden Lane, and next to him was a fishmonger named Mr. Frank Wilkisson who’s a member of a family that’s had a stand in the Old Market three generations, and next to him was a young Southerner that you’re doing good if you understand half what he says who drives one of those tremendous big refrigerator trucks that they call reefers and hits the market every four or five days with a load of shrimp from little shrimp ports in Florida and Georgia. Sitting on the other side was a lady who holds a responsible position in Continental Casualty up on William Street and comes in here for bouillabaisse, only we call it ciuppin di pesce and cook it the way it’s cooked fishing-family style back in Recco, and next to her was an old gentleman who works in J. P. Morgan & Company’s banking house and you’d think he’d order something expensive like pompano but he always orders cod cheeks and if we’re out of that he orders cod roe and if we’re out of that he orders broiled cod and God knows we’re never out of that, and next to him was one of the bosses in Mooney’s coffee-roasting plant at Fulton and Front. And sitting at the aisle end of the table was a man known all over as Cowhide Charlie who goes to slaughter-houses and buys green cowhides and sells them to fishing-boat captains to rig to the undersides of their drag nets to keep them from getting bottom-chafed and rock-cut and he’s always bragging that right this very minute his hides are rubbing the bottom of every fishing bank from Nantucket Shoals to the Virginia Capes.”

Louie said that some days, particularly Fridays, the place is jammed around one o’clock and latecomers crowd together just inside the door and stand and wait and stare, and he said that this gets on his nerves. He said he had come to the conclusion that he would have to go ahead and put in some tables on the second floor.

“I would’ve done it long ago,” he said, “except I need the second floor for other things. This building doesn’t have a cellar. South Street is old filled-in river swamp, and the cellars along here, what few there are, the East River leaks into them every high tide. The second floor is my cellar. I store supplies up there, and I keep my deep freeze up there, and the waiters change their clothes up there. I don’t know what I’ll do without it, only I got to make room someway.”

“That ought to be easy,” I said. “You’ve got four empty floors up above.”

“You mean those boarded-up floors,” Louie said. He hesitated a moment. “Didn’t I ever tell you about the upstairs in here?” he asked. “Didn’t I ever tell you about those boarded-up floors?”

VIDEO FROM THE NEW YORKER

How Oysters Can Help Fight Climate Change

“No,” I said.

“They aren’t empty,” he said.

“What’s in them?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I’ve heard this and I’ve heard that, but I don’t know. I wish to God I did know. I’ve wondered about it enough. I’ve rented this building twenty-two years, and I’ve never been above the second floor. The reason being, that’s as far as the stairs go. After that, you have to get in a queer old elevator and pull yourself up. It’s an old-fashioned hand-power elevator, what they used to call a rope-pull. I wouldn’t be surprised it’s the last of its kind in the city. I don’t understand the machinery of it, the balancing weights and the cables and all that, but the way it’s operated, there’s a big iron wheel up at the top of the shaft and the wheel’s got a groove in it, and there’s a rope that rides in this groove, and you pull on the part of the rope that hangs down one side of the cage to go up, and you pull on the part that hangs down the other side to go down. Like a dumbwaiter. It used to run from the ground floor to the top, but a long time ago some tenant must’ve decided he didn’t have any further use for it and wanted it out of the way, so he had the shaft removed from the ground floor and the second floor. He had it cut off at the second-floor ceiling. In other words, the way it is now, the bottom of the shaft is level with the second-floor ceiling—the floor of the elevator cage acts as part of the ceiling. To get in the elevator, you have to climb a ladder that leads to a trapdoor that’s cut in the floor of the cage. It’s a big, roomy cage, bigger than the ones nowadays, but it doesn’t have a roof on it—just this wooden floor and some iron-framework sides. I go up the ladder sometimes and push up the trapdoor and put my head and shoulder inside the cage and shine a flashlight up the shaft, but that’s as far as I go. Oh, Jesus, it’s dark and dusty in there. The cage is all furry with dust and there’s mold and mildew on the walls of the shaft and the air is dead.

“The first day I came here, I wanted to get right in the elevator and go up to the upper floors and rummage around up there, see what I could see, but the man who rented the building ahead of me was with me, showing me over the place, and he warned me not to. He didn’t trust the elevator. He said you couldn’t pay him to get in it. ‘Don’t meddle with that thing,’ he said. ‘It’s a rattlesnake. The rope might break, or that big iron wheel up at the top of the shaft that’s eaten up with rust and hasn’t been oiled for a generation might work loose and drop on your head.’ Consequently, I’ve never even given the rope a pull. To pull the rope, you got to get inside the cage and stand up. You can’t reach it otherwise. I’ve been tempted to many a time. It’s a thick hemp rope. It’s as thick as a hawser. It might be rotten, but it certainly looks strong. The way the cage is sitting now, I figure it’d only take a couple of pulls, a couple of turns of the wheel, and you’d be far enough up to where you could swing the cage door open and step out on the third floor. You can’t open the cage door now; you got to draw the cage up just a little. A matter of inches. I reached into the cage once and tried to poke the door open with a boat hook I borrowed off one of the fishing boats, but it wouldn’t budge. It’s a highly irritating situation to me. I’d just like to know for certain what’s up there. A year goes by sometimes and I hardly think about it, and then I get to wondering, and it has a tendency to prey on my mind. An old-timer in the market once told me that many years ago a fishmonger down here got a bug in his head and invented a patented returnable zinc-lined fish box for shipping fish on ice and had hundreds of them built, sunk everything he had in them, and they didn’t catch on, and finally he got permission to store them up on the third and fourth floors of this building until he could come to some conclusion what to do with them. This was back before they tinkered with the elevator. Only he never came to any conclusion, and by and by he died. The old-timer said it was his belief the fish boxes are still up there. The man who rented the building ahead of me, he had a different story. He was never above the second floor either, but he told me that the man who rented it ahead of him told him it was his understanding there was a lot of miscellaneous old hotel junk stored up there—beds and bureaus, pitchers and bowls, chamber pots, mirrors, brass spittoons, odds and ends, old hotel registers that the rats chew on to get paper to line their nests with, God knows what all. That’s what he said. I don’t know. I’ve made quite a study of this building for one reason and another, and I’ve took all kinds of pains tracking things down, but there’s a lot about it I still don’t know. I do know there was a hotel in here years back. I know that beyond all doubt. It was one of those old steamship hotels that used to face the docks all along South Street.”

“Why don’t you get a mechanic to inspect the elevator?” I asked. “It might be perfectly safe.”

“That would cost money,” Louie said. “I’m curious but I’m not that curious. To tell you the truth, I just don’t want to get in that cage by myself. I got a feeling about it, and that’s the fact of the matter. It makes me uneasy—all closed in, and all that furry dust. It makes me think of a coffin, the inside of a coffin. Either that or a cave, the mouth of a cave. If I could get somebody to go along with me, somebody to talk to, just so I wouldn’t be all alone in there, I’d go; I’d crawl right in. A couple of times, it almost happened I did. The first time was back in 1938. The hurricane we had that fall damaged the roofs on a good many of the old South Street buildings, and the real-estate management company I rented this building from sent a man down here to see if my roof was all right. I asked the man why didn’t he take the elevator up to the attic floor, there might be a door leading out on the roof. I told him I’d go along. He took one look inside the cage and said it would be more trouble than it was worth. What he did, he went up on the roof of the building next door and crossed over. Didn’t find anything wrong. Six or seven months ago, I had another disappointment. I was talking with a customer of mine eats a fish lunch in here Fridays who’s a contractor, and it happened I got on the subject of the upper floors, and he remarked he understood how I felt, my curiosity. He said he seldom passes an old boarded-up building without he wonders about it, wonders what it’s like in there—all empty and hollow and dark and still, not a sound, only some rats maybe, racing around in the dark, or maybe some English sparrows flying around in there in the empty rooms that always get in if there’s a crack in one of the boards over a broken windowpane, a crack or a knothole, and sometimes they can’t find their way out and they keep on hopping and flying and hopping and flying until they starve to death. He said he had been in many such buildings in the course of his work, and had seen some peculiar things. The next time he came in for lunch, he brought along a couple of those helmets that they wear around construction work, those orange-colored helmets, and he said to me, ‘Come on, Louie. Put on one of these, and let’s go up and try out that elevator. If the rope breaks, which I don’t think it will—what the hell, a little shaking up is good for the liver. If the wheel drops, maybe these helmets will save us.’ But he’s a big heavy man, and he’s not as active as he used to be. He went up the ladder first, and when he got to the top he backed right down. He put it on the basis he had a business appointment that afternoon and didn’t want to get all dusty and dirty. I kept the helmets. He wanted them back, but I held on to them. I don’t intend to let that elevator stand in my way much longer. One of these days, I’m going to sit down awhile with a bottle of Strega, and then I’m going to stick one of those helmets on my head and climb in that cage and put that damned elevator back in commission. The very least, I’ll pull the rope and see what happens. I do wish I could find somebody had enough curiosity to go along with me. I’ve asked my waiters, and I’ve tried to interest some of the people in the market, but they all had the same answer. ‘Hell, no,’ they said.”

Louie suddenly leaned forward. “What about you?” he asked. “Maybe I could persuade you.” I thought it over a few moments, and was about to suggest that we go upstairs at any rate and climb in the cage and look at the elevator, but just then a fishmonger who had finished his breakfast and wanted to pay his check rapped a dictatorial rat-a-tat on the glass top of the cigar showcase with a coin. Louie frowned and clenched his teeth. “I wish they wouldn’t do that,” he said, getting up. “It goes right through me.”

Louie went over and took the man’s money and gave him his change. Two waiters were standing at a service table in the rear, filling salt shakers, and Louie gestured to one of them to come up front and take charge of the cash register. Then he got himself another cup of coffee and sat back down and started talking again. “When I bought this restaurant,” he said, “I wasn’t too enthusiastic about the building. I had it in mind to build up the restaurant and find me a location somewhere else in the market and move, the trade would follow. Instead of which, after a while I got very closely attached to the building. Why I did is one of those matters, it really doesn’t make much sense. It’s all mixed up with the name of a street in Brooklyn, and it goes back to the last place I worked in before I came here. That was Joe’s in Brooklyn, the old Nevins Street Joe’s, Nevins just off Flatbush Avenue Extension. I was a waiter there seven years, and it was the best place I ever worked in. Joe’s is part of a chain now, the Brass Rail chain. In my time, it was run by a very high-type Italian restaurant man named Joe Sartori, and it was the biggest chophouse in Brooklyn—fifty waiters, a main floor, a balcony, a ladies’ dining room, and a Roman Garden. Joe’s was a hangout for Brooklyn political bosses and officeholders, and it got a class of trade we called the old Brooklyn family trade, the rich old intermarried families that made their money out of Brooklyn real estate and Brooklyn docks and Brooklyn streetcar lines and Brooklyn gasworks. They had their money sunk way down deep in Brooklyn. I don’t know how it is now, they’ve probably all moved into apartment houses, but in those days a good many of them lived in steep-stoop, stain-glass mansions sitting up as solid as banks on Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope and over around Fort Greene Park. They were a big-eating class of people, and they believed in patronizing the good old Brooklyn restaurants. You’d see them in Joe’s, and you’d see them in Gage & Tollner’s and Lundy’s and Tappen’s and Villepigue’s. There was a high percentage of rich old independent women among them, widows and divorced ladies and maiden ladies. They were a class within a class. They wore clothes that hadn’t been the style for years, and they wore the biggest hats I ever saw, and the ugliest. They all seemed to know each other since their childhood days, and they all had some peculiarity, and they all had one foot in the grave, and they all had big appetites. They had travelled widely, and they were good judges of food, and they knew how to order a meal. Some were poison, to say the least, and some were just as nice as they could be. On the whole, I liked them; they broke the monotony. Some always came to my station; if my tables were full, they’d sit in some leather chairs Mr. Sartori had up front and wait. One was a widow named Mrs. Frelinghuysen. She was very old and tiny and delicate, and she ate like a horse. She ate like she thought any meal might be her last meal. She was a little lame from rheumatism, and she used a walking stick that had a snake’s head for a knob, a snake’s head carved out of ivory. She had a pleasant voice, a beautiful voice, and she made the most surprising funny remarks. They were coarse remarks, the humor in them. She made some remarks on occasion that had me wondering did I hear right. Everybody liked her, the way she hung on to life, and everybody tried to do things for her. I remember Mr. Sartori one night went out in the rain and got her a cab. ‘She’s such a thin little thing,’ he said when he came back in. ‘There’s nothing to her,’ he said, ‘but six bones and one gut and a set of teeth and a big hat with a bird on it.’ Her peculiarity was she always brought her own silver. It was old family silver. She’d have it wrapped up in a linen napkin in her handbag, and she’d get it out and set her own place. After she finished eating, I’d take it to the kitchen and wash it, and she’d stuff it back in her handbag. She’d always start off with one dozen oysters in winter or one dozen clams in summer, and she’d gobble them down and go on from there. She could get more out of a lobster than anybody I ever saw. You’d think she’d got everything she possibly could, and then she’d pull the little legs off that most people don’t even bother with, and suck the juice out of them. Sometimes, if it was a slow night and I was just standing around, she’d call me over and talk to me while she ate. She’d talk about people and past times, and she knew a lot; she had kept her eyes open while she was going through life.

“My hours in Joe’s were ten in the morning to nine at night. In the afternoons, I’d take a break from three to four-thirty. I saw so much rich food I usually didn’t want any lunch, the way old waiters get—just a crust of bread, or some fruit. If it was a nice day, I’d step over to Albee Square and go into an old fancy-fruit store named Ecklebe & Guyer’s and pick me out a piece of fruit—an orange or two, or a bunch of grapes, or one of those big red pomegranates that split open when they’re ripe the same as figs and their juice is so strong and red it purifies the blood. Then I’d go over to Schermerhorn Street. Schermerhorn was a block and a half west of Joe’s. There were some trees along Schermerhorn, and some benches under the trees. Young women would sit along there with their babies, and old men would sit along there the whole day through and read papers and play checkers and discuss matters. And I’d sit there the little time I had and rest my feet and eat my fruit and read the New York Times, my purpose reading the New York Times I was trying to improve my English. Schermerhorn Street was a peaceful old backwater street, so nice and quiet, and I liked it. It did me good to sit down there and rest. One afternoon the thought occurred to me, ‘Who the hell was Schermerhorn?’ So that night it happened Mrs. Frelinghuysen was in, and I asked her who was Schermerhorn that the street’s named for. She knew, all right. Oh, Jesus, she more than knew. She saw I was interested, and from then on that was one of the main subjects she talked to me about—Old New York street names and neighborhood names; Old New York this, Old New York that. She knew a great many facts and figures and skeletons in the closet that her mother and her grandmother and her aunts had passed on down to her relating to the old New York Dutch families that they call the Knickerbockers—those that dissipated too much and dissipated all their property away and died out and disappeared, and those that are still around. Holland Dutch, not German Dutch, the way I used to think it meant. The Schermerhorns are one of the oldest of the old Dutch families, according to her, and one of the best. They were big landowners in Dutch days, and they still are, and they go back so deep in Old New York that if you went any deeper you wouldn’t find anything but Indians and bones and bears. Mrs. Frelinghuysen was well acquainted with the Schermerhorn family. She had been to Schermerhorn weddings and Schermerhorn funerals. I remember she told about a Schermerhorn girl she went to school with who belonged to the eighth generation I think it was in direct descent from old Jacob Schermerhorn who came here from Schermerhorn, Holland, in the sixteen-thirties, and this girl died and was buried in the Schermerhorn plot in Trinity Church cemetery up in Washington Heights, and one day many years later driving down from Connecticut Mrs. Frelinghuysen got to thinking about her and stopped off at the cemetery and looked around in there and located her grave and put some jonquils on it.”

At this moment a fishmonger opened the door of the restaurant and put his head in and interrupted Louie. “Hey, Louie,” he called out, “has Little Joe been in?”

“Little Joe that’s a lumper on the pier,” asked Louie, “or Little Joe that works for Chesebro, Robbins?”

“The lumper,” said the fishmonger.

“He was in and out an hour ago,” said Louie. “He snook in and got a cup of coffee and was out and gone the moment he finished it.”

“If you see him,” the fishmonger said, “tell him they want him on the pier. A couple of draggers just came in—the Felicia from New Bedford and the Positive from Gloucester.”

Louie nodded, and the fishmonger went away. “To continue about Mrs. Frelinghuysen,” Louie said, “she died in 1927. The next year, I got married. The next year was the year the stock market crashed. The next year, I quit Joe’s and came over here and bought this restaurant and rented this building. I rented it from a real-estate company, the Charles F. Noyes Company, and I paid my rent to them, and I took it for granted they owned it. One afternoon four years later, the early part of 1934, around in March, I was standing at the cash register in here and a long black limousine drove up out front and parked, and a uniform chauffeur got out and came in and said Mrs. Schermerhorn wanted to speak to me, and I looked at him and said, ‘What do you mean—Mrs. Schermerhorn?’ And he said, ‘Mrs. Schermerhorn that owns this building.’ So I went out on the sidewalk, and there was a lady sitting in the limousine, her appearance was quite beautiful, and she said she was Mrs. Arthur F. Schermerhorn and her husband had died in September the year before and she was taking a look at some of the buildings the estate owned and the Noyes company was the agent for. So she asked me some questions concerning what shape the building was in, and the like of that. Which I answered to the best of my ability. Then I told her I was certainly surprised for various reasons to hear this was Schermerhorn property. I told her, ‘Frankly,’ I said, ‘I’m amazed to hear it.’ I asked her did she know anything about the history of the building, how old it was, and she said she didn’t, she hadn’t ever even seen it before, it was just one of a number of properties that had come down to her husband from his father. Even her husband, she said, she doubted if he had known much about the building. I had a lot of questions I wanted to ask, and I asked her to get out and come in and have some coffee and take a look around, but I guess she figured the signboard sloppy louie’s restaurant meant what it said. She thanked me and said she had to be getting on, and she gave the chauffeur an address, and they drove off and I never saw her again.

“I went back inside and stood there and thought t over, and the effect it had on me, the simple fact my building was an old Schermerhorn building, it may sound foolish, but it pleased me very much. The feeling I had, it connected me with the past. It connected me with Old New York. It connected Sloppy Louie’s Restaurant with Old New York. It made the building look much better to me. Instead of just an old run-down building in the fish market, the way it looked to me before, it had a history to it, connections going back, and I liked that it stirred up my curiosity to know more. A day or so later, I went over and asked the people at the Noyes company would they mind telling me something about the history of the building, but they didn’t know anything about it. They had only took over the management of it in 1929, the year before I rented it, and the company that had been the previous agent had gone out of business. They said to go to the City Department of Buildings in the Municipal Building. Which I did, but the man in there, he looked up my building and couldn’t find any file on it, and he said it’s hard to date a good many old buildings down in my part of town because a fire in the Building Department around 1890 destroyed some cases of papers relating to them—permits and specifications and all that. He advised me to go to the Hall of Records on Chambers Street, where deeds are recorded. I went over there, and they showed me the deed, but it wasn’t any help. It described the lot, but all it said about the building, it said ‘the building thereon,’ and didn’t give any date on it. So I gave up. Well, there’s a nice old gentleman eats in here sometimes who works for the Title Guarantee & Trust Company, an old Yankee fish-eater, and we were talking one day, and it happened he told me that Title Guarantee has tons and tons of records on New York City property stored away in their vaults that they refer to when they’re deciding whether or not the title to a piece of property is clear. ‘Do me a favor,’ I said, ‘and look up the records on 92 South Street—nothing private or financial; just the history—and I’ll treat you to the best broiled lobster you ever had. I’ll treat you to broiled lobster six Fridays in a row,’ I said, ‘and I’ll broil the lobsters myself.’

“The next time he came in, he said he had took a look in the Title Guarantee vaults for me, and had talked to a title searcher over there who is an expert on South Street property, and he read me off some notes he had made. It seems all this end of South Street used to be under water. The East River flowed over it. Then the city filled it in and divided it into lots. In February, 1804, a merchant by the name Peter Schermerhorn, a descendant of Jacob Schermerhorn, was given grants to the lot my building now stands on—92 South—and the lot next to it—93 South, a corner lot, the corner of South and Fulton. Schermerhorn put up a four-story brick-and-frame building on each of these lots—stores on the street floors and flats above. In 1872,1873, or 1874—my friend from Title Guarantee wasn’t able to determine the exact year—the heirs and assigns of Peter Schermerhorn ripped these buildings down and put up two six-story brick buildings exactly alike side by side on 92 and 93. Those buildings are this one here and the one next door. The Schermerhorns put them up for hotel purposes, and they were designed so they could be used as one building—there’s a party wall between them, and in those days there were sets of doors on each floor leading from one building to the other. This building had that old hand-pull elevator in it from bottom to top, and the other building had a wide staircase in it from bottom to top. The Schermerhorns didn’t skimp on materials; they used heart pine for beams and they used hand-molded, air-dried, kiln-burned Hudson River brick. The Schermerhorns leased the buildings to two hotel men named Frederick and Henry Lemmermann, and the first lease on record is 1874. The name of the hotel was the Fulton Ferry Hotel. The hotel saloon occupied the whole bottom floor of the building next door, and the hotel restaurant was right in here, and they had a combined lobby and billiard room that occupied the second floor of both buildings, and they had a reading room in the front half of the third floor of this building and rooms in the rear half, and all the rest of the space in both buildings was single rooms and double rooms and suites. At that time, there were passenger-line steamship docks all along South Street, lines that went to every part of the world, and out-of-town people waiting for passage on the various steamers would stay at the Fulton Ferry Hotel. Also, the Brooklyn Bridge hadn’t yet been built, and the Fulton Ferry was the principal ferry to Brooklyn, and the ferry-house stood directly in front of the hotel. On account of the ferry, Fulton Street was like a funnel; damned near everything headed for Brooklyn went through it. It was full of foot traffic and horse-drawn traffic day and night, and South and Fulton was one of the most ideal saloon corners in the city.

“The Fulton Ferry Hotel lasted forty-five years, but it only had about twenty good years; the rest was downhill. The first bad blow was the bridges over the East River beginning with the Brooklyn Bridge that gradually drained off the heavy traffic on the Fulton Ferry that the hotel saloon got most of its trade from. And then, the worst blow of all, the passenger lines began leaving South Street and moving around to bigger, longer docks on the Hudson. Little by little, the Fulton Ferry Hotel got to be one of those waterfront hotels that rummies hole up in, and old men on pensions, and old nuts, and sailors on the beach. Steps going down. Around 1910, somewhere in there, the Lemmermanns gave up the part of the hotel that was in this building, and the Schermerhorn interests boarded up the windows on the four upper floors and bricked up the doors in the party wall connecting the two buildings. And the hotel restaurant, what they did with that, they rented it to a man named MacDonald who turned it into a quick lunch for the people in the fish market. MacDonald ran it awhile. Then a son of his took it over, according to some lease notations in the Title Guarantee records. Then two brothers named Fortunato and Louie Barbagelata took it over. Then John Barbagelata took it over, a nephew of the other Barbagelatas, and eventually I came along and bought the lease and furnishings off of him. After the party wall was bricked up, the Lemmermanns held on to the building next door a few years more, and kept on calling it the Fulton Ferry Hotel, but all it amounted to, it was just a waterfront saloon with rooms for rent up above. They operated it until 1919, when the final blow hit them—prohibition. Those are the bare bones of the matter. If I could get upstairs just once in that damned old elevator and scratch around in those hotel registers up there and whatever to hell else is stored up there, it might be possible I’d find out a whole lot more.”

“Look, Louie,” I said, “I’ll go up in the elevator with you.”

“You think you would,” Louie said, “but you’d just take a look at it, and then you’d back out.”

“I’d like to see inside the cage, at least,” I said.

Louie looked at me inquisitively. “You really want to go up there?” he asked

“Yes,” I said.

“The next time you come down here, put on the oldest clothes you got, so the dust don’t make any difference,” Louie said, “and we’ll go up and try out the elevator.”

“Oh, no,” I said. “Now or never. If I think it over, I’ll change my mind.”

“It’s your own risk,” he said. “Of course,” I said.

Louie abruptly stood up. “Let me speak to the waiter at the cash register,” he said, “and I’ll be with you.” He went over and spoke to the waiter. Then he opened the door of a cupboard in back of the cash register and took out two flashlights and the two construction-work helmets that his customer, the contractor, had brought in. He handed me one of the flashlights and one of the helmets. I put the helmet on and started over to a mirror to see how I looked. “Come on,” Louie said, somewhat impatiently. We went up the stairs to the second floor. Along one wall, on this floor, were shelves stacked with restaurant supplies—canned goods and nests of bowls and plates and boxes of soap powder and boxes of paper napkins. Headed up against the wainscoting were half a dozen burlap bags of potatoes. A narrow, round-runged, wooden ladder stood at a slant in a corner up front, and Louie went directly to it. One end of the ladder was fixed to the floor, and the other end was fixed to the ceiling. At the top of the ladder, flush with the ceiling, was the bottom of the elevator cage with the trapdoor cut in it. The trapdoor was shut. Louie unbuttoned a shirt button and stuck his flashlight in the front of his shirt, and immediately started up the ladder. At the top, he paused and looked down at me for an instant. His face was set. Then he gave the trapdoor a shove, and it fell back, and a cloud of black dust burst out. Louie ducked his head and shook it and blew the dust out of his nose. He stood at the top of the ladder for about a minute, waiting for the dust to settle. Then, all of a sudden, he scrambled into the cage. “Oh, God in Heaven,” he called out, “the dust in here! It’s like somebody dumped out a vacuum-cleaner bag in here.” I climbed the ladder and entered the cage and closed the trapdoor. Louie pointed his flashlight up the shaft. “I thought there was only one wheel up there,” he said, peering upward. “I see two.” The dust had risen to the top of the shaft, and we couldn’t see the wheels clearly. There was an iron strut over the top of the cage, and a cable extended from it to one of the wheels. Two thick hemp ropes hung down into the cage from the other wheel. “I’m going to risk it,” Louie said. “I’m going to pull the rope. Take both flashlights, and shine one on me and shine the other up the shaft. If I can get the cage up about a foot, it’ll be level with the third floor, and we can open the door.”

Louie grasped one of the ropes and pulled on it, and dust sprang off it all the way to the top. The wheel screeched as the rope turned it, but the cage didn’t move. “The rope feels loose,” Louie said. “I don’t think it has any grip on the wheel.” He pulled again, and nothing happened. “Maybe you’ve got the wrong rope,” I said. He disregarded me, and pulled again, and the cage shook from side to side Louie let go of the rope, and looked up the shaft. “That wheel acts all right,” he said. He pulled the rope again, and this time the cage rose an inch or two. He pulled five or six times, and the cage rose an inch or two each time. Then we looked down and saw that the floor of the cage was almost even with the third floor. Louie pulled the rope once more. Then he stepped over and pushed on the grilled door of the cage and shook it, trying to swing it open; it rattled, and long, lacy flakes of rust fell off it, but it wouldn’t open. I gave Louie the lights of both flashlights, and he examined the door. There were sets of hinges down it in two paces. “I see,” Louie said. “You’re supposed to fold it back in.” The hinges were stiff, and he got in a frenzy struggling with the door before he succeeded in folding it back far enough for us to get through. On the landing there was a kind of storm-door-like affair, a three-sided cubbyhole with a plain wooden door in the center side. “I guess they had that there to keep people from falling in the shaft,” Louie said. “It’ll be just our luck the door’s locked on the other side. If it is, I’m not going to monkey around; I’m going to kick it in.” He tried the knob, and it turned, and he opened the door, and we walked out and entered the front half of the third floor, the old reading room of the Fulton Ferry Hotel.

It was pitch-dark in the room. We stood still and played the lights of our flashlights across the floor and up and down the walls. Everything we saw was covered with dust. There was a thick, black mat of fleecy dust on the floor—dust and soot and grit and lint and slut’s wool. Louie scuffed his shoes in it. “A-a-ah!” he said, and spat. His light fell on a roll-top desk, and he hurried over to it and rolled the top up. I stayed where I was, and continued to look around. The room was rectangular, and it had a stamped-tin ceiling, and tongue-and-groove wainscoting, and plaster walls the color of putty. The plaster had crumbled down to the laths in many places. There was a gas fixture on each wall. High up on one wall was a round hole that had once held a stovepipe. Screwed to the door leading to the rear half of the floor were two framed signs. One said, “this reading room will be closed at 1 a.m. fulton ferry hotel.” The other said, “all gambling in this reading room strictly prohibited. by order of the proprietors. fulton ferry hotel. f. & h. lemmermann, proprietors.” Some bedsprings and some ugly white knobby iron bedsteads were stacked crisscross in one corner. The stack was breast-high. Between the boarded-up windows, against the front wall, stood a marble-top table. On it were three seltzer bottles with corroded spouts, a tin water cooler painted to resemble brown marble, a cracked glass bell of the kind used to cover clocks and stuffed birds, and four sugar bowls whose metal flap lids had been eaten away from their hinges by rust. On the floor, beside the table, were an umbrella stand, two brass spittoons, and a wire basket filled to the brim with whiskey bottles of the flask type. I took the bottles out one by one. Dampness had destroyed the labels; pulpy scraps of paper with nothing legible on them were sticking to a few on the bottom. Lined up back to back in the middle of the room were six bureaus with mirrors on their tops. Still curious to see how I looked in the construction-work helmet, I went and peered in one of the mirrors. Louie, who had been yanking drawers out of the roll-top desk, suddenly said, “God damn it! I thought I’d find those hotel registers in here. There’s nothing in here, only rusty paper clips.” He went over to the whiskey bottles I had strewn about and examined a few, and then he walked up behind me and looked in the mirror. His face was strained. He had rubbed one cheek with his dusty fingers, and it was streaked with dust. “We’re the first faces to look in that mirror in years and years,” he said. He held his flashlight with one hand and jerked open the top drawer of the bureau with the other. There were a few hairpins in the drawer, and some buttons, and a comb with several teeth missing, and a needle with a bit of black thread in its eye, and a scattering of worn playing cards; the design on the backs of the cards was a stag at bay. He opened the middle drawer, and it was empty. He opened the bottom drawer, and it was empty. He started in on the next bureau. In the top drawer of it, he found a square, clear-glass medicine bottle that contained two inches of colorless liquid and half an inch of black sediment. He wrenched the stopper out, and put the bottle to his nose and smelled the liquid. “It’s gone dead,” he said. “It doesn’t smell like anything at all.” He poured the liquid on the floor, and handed the bottle to me. Blown in one side of it was “Perry’s Pharmacy. Open All Night. Popular Prices. World Building, New York.” All at once, while looking at the old bottle, I became conscious of the noises of the market seemingly far below, and I stepped over to one of the boarded-up windows and tried to peep down at South Street through a split in a board, but it wasn’t possible. Louie continued to go through the bureau drawers. “Here’s something,” he said. “Look at this.” He handed me a foxed and yellowed photograph of a dark young woman with upswept hair who wore a lace shirtwaist and a long black skirt and sat in a fanciful fan-backed wicker chair. After a while, Louie reached the last drawer in the last bureau, and looked in it and snorted and slammed it shut. “Let’s go in the rear part of the floor,” he said.

Louie opened the door, and we entered a hall, along which was a row of single rooms. There were six rooms, and on their doors were little oval enamelled number plates running from 12 to 17. We looked in Room 12. Two wooden coat hangers were lying on the floor of it. Room 13 was absolutely empty. Room 14 had evidently last been occupied by someone with a religious turn of mind. There was an old iron bedstead still standing in it, but without springs, and tacked on the wall above the head of the bed was a placard of the kind distributed by some evangelistic religious groups. It said, “The Wages of Sin is Death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.” Tacked on the wall beside the bed was another religious placard: “Christ is the Head of this House, the Unseen Host at Every Meal, the Silent Listener to Every Conversation.” We stared at the placards a few moments, and then Louie turned and started back up the hall.

“Louie,” I called, following him, “where are you going?”

“Let’s go on back downstairs,” he said.

“I thought we were going on up to the floors above,” I said. “Let’s go up to the fourth floor, at least. We’ll take turns pulling the rope.”

“There’s nothing up here,” he said. “I don’t want to start up here another minute. Come on, let’s go.

I followed him into the elevator cage. “I’ll pull the rope going down,” I said.

Louie said nothing, and I glanced at him. He was leaning against the side of the cage, and his shoulders were slumped and his eyes were tired. “I didn’t learn much I didn’t know before,” he said.

“You learned that the wages of sin is death,” I said, trying to say something cheerful.

“I knew that before,” Louie said. A look of revulsion came on his face. “The wages of sin!” he said. “Sin, death, dust, old empty rooms, old empty whiskey bottles, old empty bureau drawers. Come on, pull the rope faster! Pull it faster! Let’s get out of this.”

Published in the print edition of the June 28, 1952, issue.

Joseph Mitchell, who died in 1996, began writing for the magazine in 1933.

No comments:

Post a Comment