There might be a French word for it, or even something even more abstruse, in Latin. But I've never heard it, so maybe there isn't. Maybe it's just me.

I'm talking about that sense you get--brought on by three notes from a popular song, the clink-clank of an old VW engine, the smell of charcoal burning in a cozy home somewhere, or even the slim warmth of the sun against the coolness of an early-spring breeze.

All at once, from seemingly nowhere, your past comes galloping back to you, like a lost and wayward horseman of the apocalypse. You're suddenly no longer in whatever year this is, you're suddenly no longer limping along hobbling into your end-times. No, you're back on a ballfield, fit and girded with muscle and sinew. Not without worries, no. No one is ever without worries, but without worries that, half a century later, seem to add up to anything of consequence.

Not too many moments ago, I was walking along the beach in this sunshine with Whiskey. She's my golden retriever and she just turned ten years old.

She's been through a host of debilitating illnesses--cancer, to name one. Two years ago, just after she turned eight, we thought she was a goner. But my wife has found care for her better than the likes an eight-term-Senator could get from the Mayo Clinic. And today she's ten.

To celebrate, we took her to a small sliver of beach on the Long Island Sound, not far from the rickety covid-cottage we bought when the plague and trump's lies about it killed one-million Americans.

Whiskey doesn't keep a scrapbook or a diary or even use that most-inadequate form of human communication, words. But she lets us know how much she enjoys the sea.

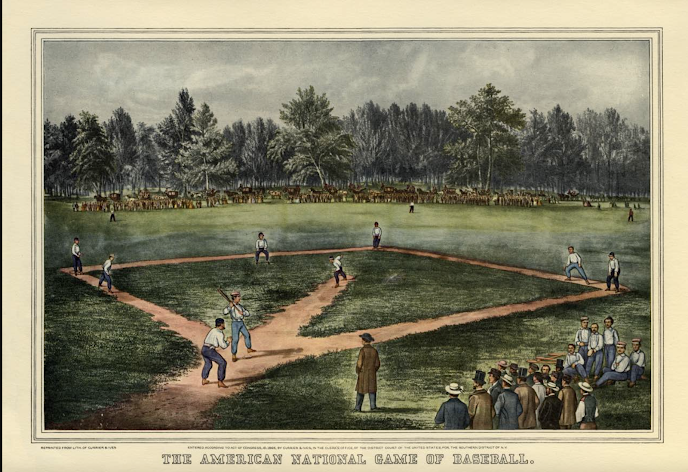

There's her toy duck to fetch in the waves. Driftwood to chew. Holes to dig in the sand and good places to roll over and dry herself off. Some of the earliest games of base-ball (they hyphenated it in the old days) were played across the Hudson from Manhattan, in Hoboken, New Jersey in a place they called the Elysian Fields.

That's the beach and the sea and the sand and the birds to Whiskey.

Elysia.

That's the feeling I was reminded of momentarily as I chased after her vying for her duck.

We were playing a game in early April in Central Park on a field that was more caked-over tire ruts than field. The grass was dead. Drug dealers roamed the outfield and would try to sell you joints between pitches. There were broken bottles everywhere and in attendance there were more rats than students.

That was New York in the early 1970s. A New York all of us who were there miss. A New York of urine smells and muggings and too tall buildings and anger and perverts and foreboding subways and hot pretzels, two for a dollar, C&C cola another thirty-five cents.

I can't remember what high school we were playing, but I do remember it was cold. Cold like today.

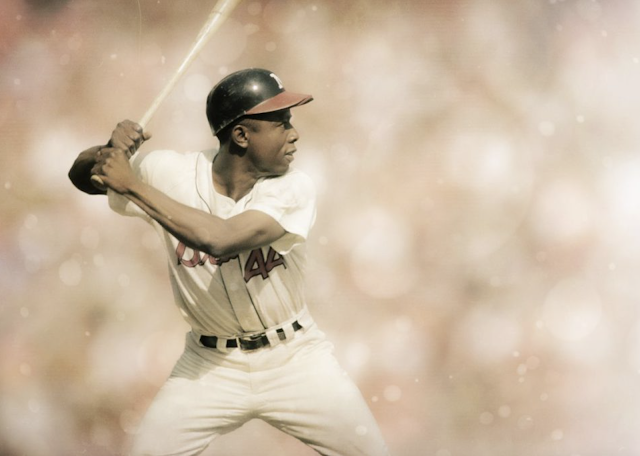

I had seen a photograph somewhere of Henry Aaron wearing a windbreaker under his uniform top and I did the same. It was just about the stupidest way you could wear a windbreaker--you'd have to take off your jersey if you needed to remove the jacket. It probably made as much sense as wearing a baseball cap with the sun-visor in the back. But everyone seems to do that today--I guess for about the same reason, I was dressed like an idiot.

We laughed when their pitcher warmed up--we were the visitors by dint of a coin flip. We shouted his way and called him a rag-arm. It was pretty standard baseball fare, and probably has been since those games a century earlier at the Elysian Fields.

Nevertheless, going into our last at bat, I think we were down something like 4-2. And those two runs had come more due to their ineptitude than any prowess we had shown with our lumber.

Their arm was still ragging it in, but still we couldn't hit the ball. It had movement or he threw something baseball denizens call a heavy ball. Whatever it was, we couldn't handle Rags.

Then all at once, with two down, Muttley walks on four pitches or five. He stole second so he could score on an outfield hit and Kong dragged a bunt and moved Mutt over to third and got to first himself.

In the second inning, I had hit a double. But I had slid bad, putting my right hand out to break my slide. Today orthopedists call that a FOOSH. A fall on outstretched hand. Back then, I just knew I couldn't bend my right thumb.

There was a girl watching from their side. We had met at a party a few weeks earlier and had made out for an hour in some dark hallway. We had had in the intervening time a few bated phone calls. Desultory. The way I like things.

I don't remember her name, but I remember her hair in the waning of the afternoon sun in the coolness of April. It was off-blond as if it had been bleached by a thousand summers of sea and sun. And it was a tangle of snarls, like Medusa with bed-head. But as I looked at her from my side of the diamond to her's, where she stood with a gossip of girlfriends, I was frozen.

Ten years before this, not far from where were playing ball that day, my mother had dressed me and my older brother in proper-little-gentlemen's camel's hair coats and we waited on line to see the Mona Lisa in her first-ever appearance in the New World.

That girl that I had made out with night on that afternoon in that weakening sunlight made the Mona Lisa look like the 4th Place winner in the Miss Industrial Progress Beauty Pageant, held in Asbury Park every year since 1913.

It was my turn to bat.

I didn't tell Babich, my coach, that I had to hold the bat without using my thumb. He'd have pulled me from the game. And you can ask anyone who's ever known me, I don't like to give up my swings at the plate for anyone. In fact, when I was in a junior league--I was just 11 or something--the coach told me that I was going to start the next day, having spent most of the season on the bench. It rained the next day and the game was canceled. I still haven't quite forgiven the gods for that.

I went to the plate, my windbreaker crinkling against gusts. I gripped the bat with mostly my palms, unable to securely hold the wood.

The first pitch came in up and out and for about the only time in my life I didn't have the strength to pull it--raggy as the pitch was. I went with it and shoved it over the second-baseman's head, in a gap between center and right. It thudded into the cold turf and after bumping twice or four times, sat there like an obese meteorite.

The pain from my broken-thumb-hit rattled through my arms like an electric shock but Muttley and Kong were in and I was safe on second standing up. Pearl was next at-bat. I ran with the pitch, nearly collided with the shortstop as he tried to field Pearl's high-hop grounder and kept running, not even pausing at third. The throw from short to first went awry, Pearl was on first, and I had scored. We led 5-4.

I looked over at Mona, what I called the girl whose name I couldn't remember. I gave her a little smile and a wave with my busted mitt. She kept me half alive by smiling and waving back.

All that happened when I was on the beach with Whiskey today, on her 10th birthday. And all because of the sun and the breeze and something I didn't even know was there hit me in a certain way. And just like that, I was alive. Alive in my past.

No comments:

Post a Comment