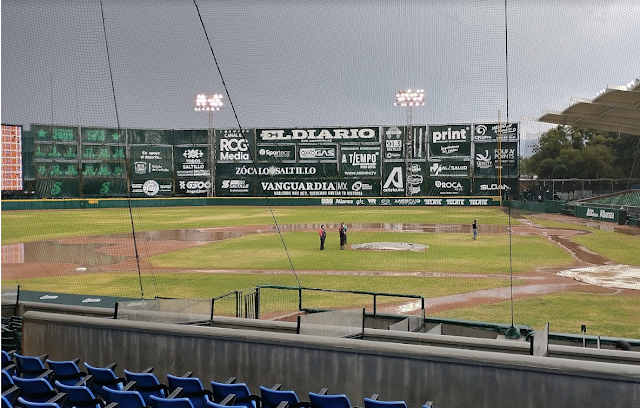

It was unusual for the Seraperos de Saltillo to have a practice at Estadio de Beisbol de Francisco I. Maduro during my one long season playing under the all-seeing and all-punishing Mexican sun in Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico. But our losing ways had been losinger than usual and our manager, Hector Quetzacoatl Padilla, aka, Hector Quesadilla, thought it wise to try to correct some bad habits before they came worse habits.

In other words, Hector called practice this evening because too many of the Seraperos were doing things their way and not his way. Playing with their shirts untucked, with their sanitary hose down about their ankles, showing up late to the ballpark, or the worst sins of all in the deep eyes and unforgiving strictures of Hector, missing the cutoff man on a peg from the outfield, missing a sign, or bunting one into the air for an easy hip-pocket catch by the opposition's backstop.

We played continuously that summer. Often we averaged more than a game a day for a stretch of two weeks or three. "You don't make money if you don't fill the ballpark," I heard one official from the team mutter once, as we set off on our rickety team bus to play nine games in seven nights. And so, we played until we dropped and the we picked ourselves up and played some more.

As a consequence the chances we had to practice were limited usually to loose pepper before the game, some desultory batting practice, arm-strengthening long throwing, and routine shit, like shifting when a lefthander came up, or learning little niblicks of tricks like as you were running the bases, drawing a throw from the outfield so the lead runner could advance.

But this was a full-fledged practice after a twilight loss to the Olmecs or the Stevedores or the Pelicanos. This was a wind-sprint, puke on the warning-track kind of practice. Because Hector was mad.

He was mad at the nothingness of the team. The lack of bite and the lack of fight. He was mad that too many of the boys were just getting through the season, not fighting through the season.

Hector, when he was a player, slid spikes out into second even if his team was down 13-2. There was no phoning it in in Hector's world. Baseball was a way away from the crushing horror of his childhood and giving up on baseball, even during a single, fleeting moment of lassitude, signaled a return to the pain of a father who hit you--and not with an open hand--and sleeping five to a mattress in a two-room wooden shack full of

brothers and empty stomachs.

A life without heart or health or hope. A life of hell and helplessness. Baseball was the out from that, and Hector played every game like he was playing death in a Bergman movie and he was always one move behind.

We clambered into groups according to our positions. I was in with the "bend-over" infielders, the guys who had to crouch at the knees and bend at the waist to do their defensive job. The first basemen were off on their own, working with Gulliermo Sisto on their footwork and their scooping bad throws out of the dirt. Gordo Batista worked with our two catchers--getting them to stick their fat Indio asses almost onto the dust to block against passed balls, and then pop up like a child's toy to make the wicked peg to second.

The outfielders, five of them, practiced dumb stuff, like staying in the game not looking for pretty girls in the stands and hitting the cut off and backing up the one-over outfielder lest one bound past him.

Hector was with us bend-overs, hitting us sharp grounders to our left or to our right, trying to get us to leap like Brooks Robinson to stab the ball before it could escape our clutches for extra bases.

Hector was particularly angry at me that night. Earlier that day, a rocket shot by me and I reacted too slowly and tried to compensate by grabbing at it barehanded with my right hand because I was too molasses to dive and get it. From where the liner hit my hand, my hand was swollen like an overstuffed Cuban sandwich and it pulsated like a ringing telephone.

Then, at once, the lights in the decaying stadium went off. The stadium was supposed to be a showcase--a modern wonder of the baseballers' art. But by the time bribes and graft got done with it, half the wooden seats had no backs, half the stairways had no railings and the infield was covered in rocky littoral, not major league loam.

The lights went out because it was nine-o'clock and the grounds' crew turned the lights out and disappeared for the night. We breathed a breath of thank god and began to leave. But Hector stopped us.

The moon was bright and Hector gathered us in. "We will practice with our ears and not our eyes," he said. "We will hear what the wood says when it hits a ball. We will listen where the wind blows a fly ball and will sense the ca-bump of the enemy's spikes and calculate when we can throw him out or not. We will listen to the sound of the game."

Hector fungoed grounders to the infielders--hard, short, fast-bouncing hits to our right or to our left. He wanted us to learn, to be like Willie Mays and anticipate with 99.999% accuracy the vector of the ball before the ball itself even knew. The great ones, Hector said, could do so. Clemente, the Pirate of Pittsburgh. Mays, the Giant of San Francisco. Brooks, the

be-wingéd Oriole from Baltimore.

Like my own be-spikéd feet, the Serapero infielders had ears of clay. Once, only once, I dove to my left and heard a low grounder into my Rawlings 'Finest in the Field' glove. But that leather embossed slogan, like such much else that emanated from el Norte was a lie and an over-promise. I was not, and never would be the finest in the field, more apt, I was the fuck-up in the field.

I said to Hector across the infield in my bad high school Spanish, words I knew he might understand. "I am no Vayu," I barked as if talking to a bad dog, "I am no Vayu, the ancient god worshiped by the even more ancient Persians."

"No se," Hector growled back.

"I am no Vayu," I said, echoing myself. "The vital breath of the world, is not the same as the vital breath in my human body. I am disconnect. Incongruity. Think left, go right."

Hector laughed at that. To me, Hector was an easy-laugh. Our senses were connected that way which is why he quickly became my first father and I his only son. Even when he was mad at me which was unusual, he loved me like my own father never did.

|

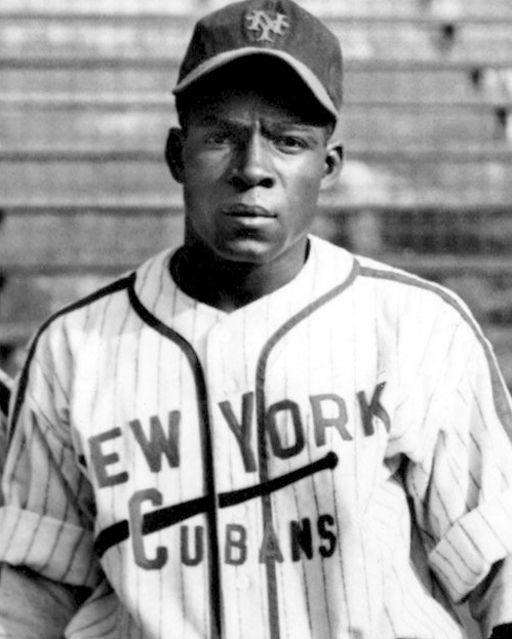

| Orestes was born not with feet but with rockets. |

"Cosmos and person are one in one person in ten million crowds of people. Perhaps Francisco I. Maduro himself had that vital breath, or Minoso of the Chicago pale hose who was never thrown out no matter how like a wild javelino he ran. But Porfirio Diaz gunned down the breath of the people and kept his kingdom of Mexico, as unvital as he was to anything but his own greed. And Minoso, black, was kept out too long because of white."

He shot another grounder my way and I fielded it in the dark cleanly across my body. I took two half Nijinski hops and zinged the ball across the infield to where the first basemen were but they did not see, hear or anticipate the sphere's arrival. It flew to Sisto's face through the dark and missed his prodigious beak only at the last minute, interrupted by the instincts of his hummingbird reflexes.

"Es totalmente," Hector shouted and we left the dark of the field for the gloom of the dripping locker-room. I stayed for a moment on the field and then lay on the dessicated grass between home and third. Hector lay down next to me and up at the lonely stars we stared.

"We are two people," the old man said in his mountain Spanish. "We are two people in one cosmos on one planet in one city in one stadium on one team. We are two people in one cosmos. We are not the vital breath of anything."

"Maybe because most nights we are too tired to even breathe" I answered.

We blinked against the blinking of the stars--more stars than the number of people at the most crowded of celestial ballparks.

"We are not the vital breath of anything," Hector repeated and his growl of a voice reverberated from Alpha-Centauri back to me.

"Except each one of us is the vital breath to the other. Your breath is vital to my breath is vital to your breath" Hector ended.

"Each one of us vital to the other," the stars and I repeated.

We breathed and talked to the blinking stars without blinking.

The stars were bright. The lights in el estadio stayed dark. There was no sight to be seen and no seens to be sighted. Yet, ever-groping at the molecular darkness, we somehow found our way. We found a beacon, unblinking, in the dark.

No comments:

Post a Comment