Some of the oldest stories in the world have been newly translated, newly-massaged and just a month or so ago, newly published.

If you want to read tales even more ancient than the leftovers in my deceased mother's deceased Frigidaire icebox, you'd do well to pick up and read Sarah Iles Johnstone's "Gods and Mortals: Ancient Greek Myths for Modern Readers." You can buy it here.

Perhaps among the most horrible and most disgusting times among the five-billion years of earth. All horrible and disgusting times--from the tyranny of the crusading conquering church, to Stalin's Russia, to Hitler's Germany, to Mao's China, to Trumpian America have something in common. They are times of moral absolutism.

They are times when there is absolute right and wrong. Absolute good and evil. Absolute allowed to live and destined to be punished.

Horrible and disgusting times are virtually always marked by a moral "My way or the highway-ist" thinking and today's world--where guns kill nine-year-olds and nine-year-olds are forced to carry their rapist's spawn represents the nadir of small L liberalism and acceptance.

Back about 1900 years ago, the Roman empire lived through a couple hundred years where moral absolutism held sway. (BTW, 300 years of history out of the 200,000 years of humans on earth is equivalent to 54-seconds in an hour-long meeting.)

Back about 100 CE, the Roman empire lurched between an embrace of the old gods, Jupiter and Company, and the thrall of the new gods, Jesus and Company. If emperor A backed Jupiter and bad shit went down, emperor B would assume power and lurch to Jesus. The Roman empire and its institutions would careen back and forth between morality systems like an old game of Atari Pong but with deadlier consequences.

That is why they are so timelessly valuable.

People (and gods) are not heroes. They are not perfect. They are wrong as often as they are right. They are good as often as they are bad. They make mistakes, they are punished--sometimes. And the sins (and in the case of Poseidon, the fins) are the fathers and mothers are visited upon the children for time immemorial.

Even Heracles, who in the Disney movie called Hercules went from "zero to hero," was <er> somewhat flawed. I mean, what kind of man impregnates fifty daughters of a king and then kills their fifty sons?

A long time ago I arrived at something I inelegantly call the 60:40 rule. (I have a rule for just about every number from one to one-thousand. Someday, maybe, I'll publish them.)

I had just finished yet another 900-page book on Winston Churchill. I quickly realized that the courageous man who you can argue save Western civilization and world Jewry was a fuck-face about 40-percent of the time. He had troops fire on striking Irish workers and kept hundreds of millions of Indians under England's sweaty colonial thumb.

I think 60:40 is right for just about every appraisal.

From corporate leaders to new CCOs to politicians. Good ones are decent about 60-percent of the time and screw up about 40-percent of the time. Bad ones are reciprocal.

Of course, there are always trumpian outliers and out-liars. But most people fall into the realm of 60:40.

Our problem as a civilization comes when we deify or make heroic humans and their errors. When we believe we can be absolutely right. That best practices make things better. And that we can materially improve our odds of success.

"Gods and Mortals," the book is about 540-pages long and is divided into 140 different stories. That means each story is about three-and-a-half pages long--about the length of a Bazooka Joe comic strip.

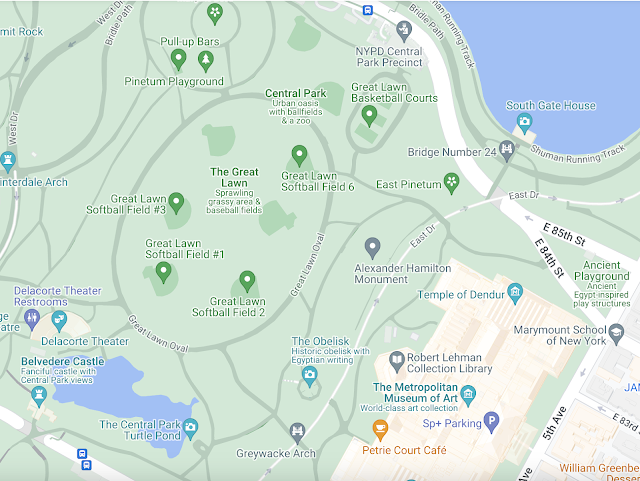

If you get on the train at 14th Street you can read about Oedipus gouging out his eyes by 23rd Street. And you'll be a better person for it.

You don't have to read the book as I am from cover to cover. You can hit it like a Golden Corral buffet. If you want to start with a green salad, ok. But if you want to start at the fettuccini Alfredo, that's ok too. Like most seminal stories, they have no beginning, middle or end. They, like the world, keep spinning. Get on and off wherever you want.

The point here today--it's Friday, after all--is simple. The world is full of pain and strife and suffering. And also laughter and joy and love. They rocket back and forth, those extremes, like two Marvel heroes playing hyperactive ping-pong.

Just try to remember a natural law of the universe, physics, advertising and Isaac Newton.

For every action, there's an equal and opposite reaction.

Keep trying to be a decent human being but keep your guard up. You never know when or where a roundhouse is coming from.

--