I don't know if this is a good idea or a bad idea. That's like so many ideas, I suppose. Ideas are like red wine. They need to breathe a little bit before you can determine whether or not they're worth it.It's Sunday morning as I write this and I just got back from the local supermarket--a behemoth of a store that has everything, except what you want.

As a Jew on the Gingham Coast of Lily Pulitzer Connecticut, nothing makes you feel quite so estranged from the world around you as looking at the Kosher section of a supermarket in a non-Jewish neighborhood. No matter what the season their entire section consists of little more than too-sweet grape juice and Yahzreit candles. You can commemorate the dead, anyway. And get Diabetes 2 while you're at it.

One thing I notice every week as my wife sends me hither with a 12-page single-spaced list full of things they don't have anywhere outside of Dean & Deluca or Zabar's, is that just about every time I shop, something goes haywire and I feel somewhat wronged.

That's not neurosis or aggrievement on my part--it's just that today, everything is done in such a slovenly low-wage manner that something always goes wrong. I'm thinking of the line allegedly uttered by astronaut John Glenn as he hurtled in his capsule back to Earth at something like 18,000 miles per hour.

"I realized everything around me was based on a low-bid."

That's life in America today. Whether you're staying at a Motel 4 or the Four Seasons. Everything is crap because management is always bent on maximizing profit and thereby, de-contenting everything else. So whether it's the plastic bag that breaks the moment you put an ear of corn in it, or the broken keypad on the gas pump so you can't enter your zip code, everything is worthy of an apology.

[My cousins from Boca flew from Atlantic City, where Howard and Deb have a beach place back to Florida on Spirit Air. Spirit Air cheaps on everything. Except the CEO's salary. He'll make $60 million this decade.]

Though I run an agency now--the agency runs around me, I wonder. I hire mensches only and work only with clients who have had the same austere upbringing I have. Accordingly, and oddly, meetings seem to start on time and end on time. People say please and thank you. And when something screws up--or takes longer than it should, as things almost invariably do--we all know how to apologize.

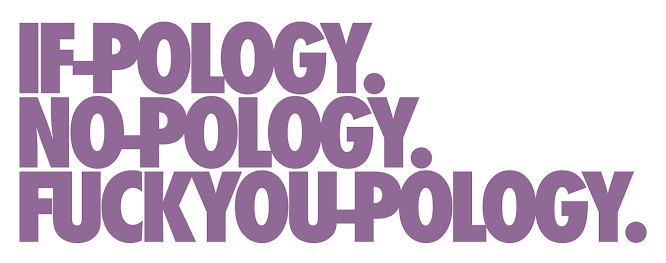

What I've noticed from my supermarket sojourns--and from my nearly 40 years of agency life--is that today the apology is all-but meaningless, if it is given at all.

Mostly, you get an if-pology. "I'm sorry if I offended you. I'm sorry if I did that. I'm sorry if you took that the wrong way." Like auto-insurance in New York State, this is a no-fault apology. The offending incident offends because of your interpretation not the antagonist's errors.

So, you might get copy that has typos or that's too long--according to a structure you've established. What you'll get as an apology is a back-pedal and an ok, little more.

Coming back from the city--my home--to Connecticut where I am a stranger in a strange land, I brought in a Ziploc bag full of six years and eleven pounds of change I had accumulated.

They have "Coin Star" machines in the grocery store, and for a mere 12.2 percent of your total (usury) they'll convert your anachronistic coins into credit or more useful paper money.

The machine dutifully printed me out a credit slip, redeemable at the cash-register for $168.63, which I assumed when I handed the sleepy-eyed cashier the slip, would be taken off my total.

When I was done checking out and bagging my own groceries in my own bags, the total for the week was roughly the same as it is every week.

I said to the young lady, "Does that include my credit for my coins?"

She finished closing her half-closed eyes and said, "Sorry, I forgot."

She stared blankly at her keyboard and didn't know what to do.

Another sleepy-eyed cashier called over.

"Send him to the Courtesy Desk," a misnomer if I've ever heard one, on the order of a lost and found at Treblinka.

There was no, "I'm sorry." No, "let me do that for you." Nothing.

I got to the courtesy desk and there was no one behind the counter.

"Hello," I falsetto'd. "Hello."

In six minutes a sleepy-eyed older woman came slowly out from the back. She moved as fast as a three-legged dog.

I explained that the cashier forgot to give me my $168.63 and I wanted it.

"No worries," was her standard courtesy.

Slowly, like a two-legged dog, she counted out my money. No big bills, of course, this is the courtesy desk, not Jerome Powell's Fed. And what would a giant supermarket be doing with a $50?

For the life of me, I don't know what "no worries" means. Of course, you have no worries. Your time wasn't wasted and you didn't have to go to two counters for one-counter's worth of service. You also didn't have to pay roughly $20 for the inconvenience of having no worries.

If I ever returned in a senior position to any sort of agency job--or any job--ever again, I would spend a week with every employee on how to apologize--on the very barest and most basics of decency.

Maybe this is a generational thing and my dying generation has different standards and expectations from everyone else. And maybe it's my generation's fault, because we've turned every job into a low-wage, low-skilled endeavor.

But whether it's waiting 22 minutes for a sandwich the sandwich place promised to have ready 22 minutes earlier or the lack of service in customer service, I'm upset.

I work with clients every day--a lot of that work involves the meaningless phrase "digital transformation," and its effect on the workplace and customer retention.

If it were me, I'd forget about digital transformation for at least five years.

I'd wake up to the notion that everybody, now and again screws up. Sins of omission or commission. Hopefully not emission. When you do, get on with it. Say you're sorry. Fix what you did as soon as you can. In fact, over-compensate. And learn from it.

As for digital transformation, I'd get to it once I had spent the time actually teaching people how to treat other people with kindness, generosity and respect.

There's a lot of transformation--digital or otherwise--that would come from respect.