One of the cosmic problems of the world is that the more we try to get our world in order, the more out of order our world becomes.

Dashiell Hammett wrote about that ontological oxymoron better than any Spinoza, Kant or Heidegger, and Hammett wrote pulp novels. As much as anything else, that should prove my point.

The Hammett I'm referring to comes from the chapter "G in the Air," from his masterpiece, "The Maltese Falcon." I've written about this before. But certain wisdom is like painting the Golden Gate Bridge. As soon as you're done with it, you have to start it again at the beginning.

“Here’s what had happened to him [Flitcraft]. Going to lunch he passed an office-building that was being put up—just the skeleton. A beam or something fell eight or ten stories down and smacked the sidewalk alongside him. It brushed pretty close to him, but didn’t touch him, though a piece of the sidewalk was chipped off and flew up and hit his cheek....

"Flitcraft had been a good citizen and a good husband and father, not by any outer compulsion, but simply because he was a man who was most comfortable in step with his surroundings...

"Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things. He, the good citizen-husband-father, could be wiped out between office and restaurant by the accident of a falling beam. He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them. It was not, primarily, the injustice of it that disturbed him: he accepted that after the first shock. What disturbed him was the discovery that in sensibly ordering his affairs he had got out of step, and not into step, with life."

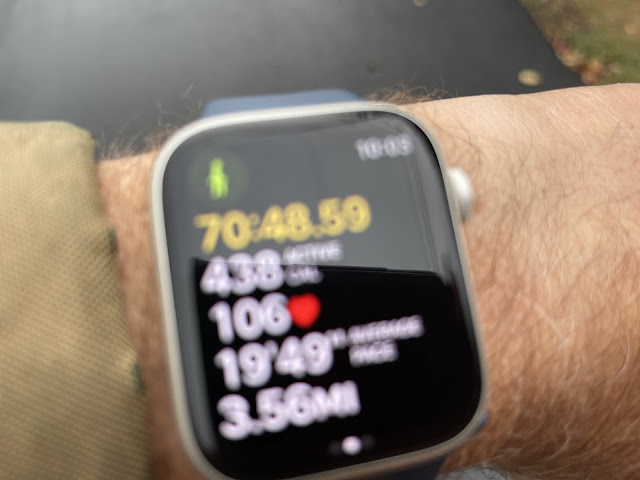

This morning, a cold, rainy morning in Connecticut, I delayed my daily 3.56 mile walk for the rain. When the drops finally became bearable, I set out along the sea. It was later than I like, and I thought I'd log a mile and try to make up the distance later.

As those who read in this space know, I have been reckoning with the need for hip replacement. I've gotten more recommendations of doctors than I know what to do with. But my natural reticence, busy-ness with work, and, yes, fear, have stopped me from making a single appointment. I've even ignored my wife's suggestion (she's already had both hips replaced) to get a cortisone shot.

Within the first hundred yards this morning, on a seawall above the sea, I noticed something: Nothing.

I had no pain.

I turned up the dial on my pain-meter. I was trying to get a pain reading. I finally got one. But the pain was nowhere near what it was just yesterday. At the end of my walk, I didn't stop. I tacked on another half-mile, because there was no pain.

That lack of pain sent me back to Saltillo, Mexico and my one long-season with the Seraperos de Saltillo in the Mexican Baseball League (AA.)

I had played baseball my whole life, but even in some of the intense summer leagues I played in, you rarely play more than twenty games a month. In the Mexican League, there were times where we consistently played ten games a week, week in and week out, many of those in Magic Chef oven conditions under the blazing Yanqui-hating Hun of a sun.

During those games, hurt happened. As one of the league's few Gringoes, I got hit by a lot of horsehide, knocked down by even more. I got Marichal'd in the forehead with a bat. I got spiked and re-spiked. I caught line-drives off my chest and more than a few I bracketed between my cheekbone and my Rawlings "Finest in the Field" Brooks Robinson-model third-baseman's glove.

I took a licking and kept on ticking. Even if I couldn't keep time.

Here's one such account of one of my travails:

In the sixth, Andre got wild. He walked their first guy, then threw a wild pitch past Buentello. Their runner went to second, so Andre walked their next batter to set up a possible double-play.The next thing I knew, I was back on the stony infield dirt flat on my ass. Their guy had hit one so hard the line-drive struck me in the chest before I heard the sound of the bat on the ball. I hadn’t even had the chance to get my glove up. The ball hit me dead in the chest but somehow I held onto it.Diablo, our shortstop, quick like Balanchine, grabbed the ball off my chest and doubled their guy off second. Then Adame pivoted and nailed their runner off first on a sharp throw to Salome Rojas at first. It was our first triple-play of the season, our last and our most-unusual.I was still down on the dirt, the wind that had been in my lungs knocked to Timbuktu. Nadeau came running over to me. He got down in a crouch and put his face near mine. “Jorge,” he said, “say it: What’s it to you, Andre Nadoo?”

I lay there for a minute or more. The team was gathering around me, including our back-up shortstop, Jesus "El Doctor" Verduzco, who spent his off-season as a third-year medical student at Tecnológico de Monterrey, ergo his grandiloquent moniker.

“Give him some room,” Verduzco said.

Verduzco, "El Doctor," was the one with the diagnosis. During one of my run-ins with mortality, when I was hit by someone or something harder than my bones or my muscles, Verduzco told me something I thought of this morning.

"You have dumb bones," Verduzco said. "You have dumb bones. Your bones, your muscles, your brain and your heart, they are all dumb. They are too dumb to give in to pain."

"Dumb bones," I said dumbly.

"Dumb bones," El Doctor confirmed. "They do not feel what they should feel. They forget immediately. They recover. They rebound. They bounce back. You have dumb bones. They do not gain wisdom like a dog you can train or even a flea in a circus. They remain as dumb as a stone. A dumb stone."

I ran a diagnostic check of my torn right rotator, and my arthritic left. My bone-on-bone hip. The wrenched right knee and ankle that are compensating for that hip. On the great orthopaedist pain scale that were a three or a four.

Child's play.

I've seen a lot of doctors in my times. I've seen a psychiatrist once a week for forty years. I have a daughter who's a Clinical psychologist and a friend who's also a therapist.

I have heard no better diagnosis from any of them: I have dumb bones and always will.

My bones hurt some time. They're bones, after all. My soul hurts too. As the world is growing warmer--to extinction--it's growing colder, too. My soul aches for the pain of so much. The growing, accelerating fission of pain. Pain that metastasizes like people cutting in an airport line to board ahead of their group.

Pain.

As Beckett wrote in "Godot,"

I won't tell if you don't.

No comments:

Post a Comment