Since my wife and I Covided out of Manhattan nearly two years ago and bought our broken-down little cottage on the sea in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, we have taken to spending about two weekends in three exploring what there is to see in our transplanted environs.

If the New York metro area were an independent country (and with the state of America today, I wish it were) it would be about number 60 by population of the 237 countries counted by the Central Intelligence Agency's World Fact Book. Putting greater- New York's population at an even 20 million, it would be just behind Mali and just atop Kazakstan.

That's a round-about way of saying there was so much to see and do when we were living in New York, we seldom took day trips out of our immediate area. Why would we?

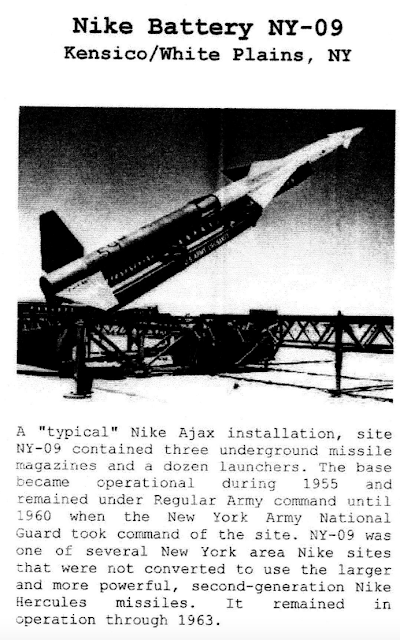

We could take a four-mile walk to the Bronx and see Edgar Allen Poe's cottage or a forty-minute drive to White Plains and see old anti-Soviet surface-to-air missile sites when we were staring eyeball-to-eyeball with Russia, like we still are.

In any event, on Saturday, I filled my 1966 Simca 1500 up with a precise mixture of aviation fuel, kerosene and leaded gasoline and we drove north about an hour to the capital of Connecticut, a benighted small city called Hartford.

In my long lifetime, Hartford has tumbled from the richest city in the United States (it's still, somewhat, the seat of the American insurance industry) to the absolute poorest. Today, a full one in three of its residents lives under the poverty line. Hartford is a near-perfect example of discriminatory policies that have wreaked havoc on so many people of color.

With neighborhoods redlined by color, no mass transit, schools supported by plummeting property valuations and jobs fleeing the once-industrialized northeast, Hartford's crime rate is nearly sixty-percent higher than the US average and fewer than seven kids in ten graduate from high school.

|

| 140 years ago, Twain and Stowe were next-door neighbors. Today much of the surrounding neighborhood is abandoned. |

However, the Hartford my wife and I drove to was the Hartford of about 130 years ago. On one block, currently surrounded by moderate blight, are the well-preserved homes of America's two most-popular and acclaimed authors: Harriet Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin (19th Century America's second best-selling book, after the Bible) and Mark Twain.

Twain was of more interest to me--mostly because despite being, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, the "woman whose book started the Civil War," Stowe and her writing haven't aged well. The less said here, the better.

While in Hartford, and surrounded by his wife and three daughters, the peripatetic Twain settled down and wrote. Really wrote.

He lived there for 17 years, between 1874 and 1891 and wrote in 1876, "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer," in 1881, "The Prince and the Pauper, followed "Life on the Mississippi," in 1883, culminating in "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," in 1884. That's four major novels in eight years. While having children running around. All while Twain himself toured the nation imitating Hal Holbrooke.

Twice while touring Twain's house I thought of advertising. Both times involved the lock-step adoption of open-plan workspaces by nearly every agency in the space of just three or four years. If agencies brought as much action and unanimity to their DEI efforts as they had to cutting their rent, our business might be today in a different place.

Twain's first office was adjacent to the nursery where his daughters played, were schooled and slept. Twain wanted to see them--he had traveled so widely and adored them so much. But he couldn't focus with that sort of open plan. Too much distraction.

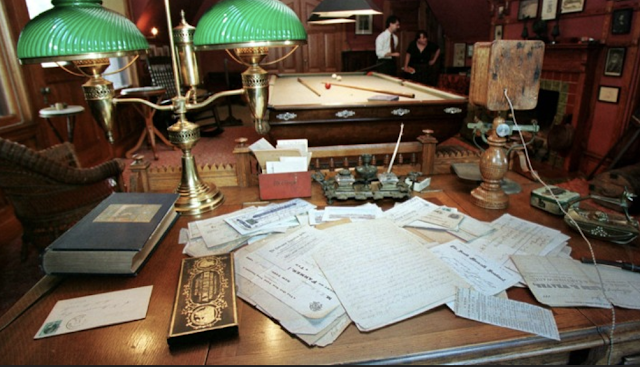

|

| Twain's billiards' room. |

So, Twain moved up to the third floor, to his billiards room. Again Twain tried to write, but snooker was too great a distraction. Finally, against the tumult of that open plan, he wedged his desk into a tight corner and got down to business.

|

| Twain's desk was a mess. A good sign of a fertile mind. |

The quiet he found worked.

As I said, four major works in just eight years.

Quiet work works.

No comments:

Post a Comment