One of the (many) things I think our species gets consistently wrong is time. In Pulitzer-Prize-winner Ed Yong's new book, "An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us," (pictured above) Yong compares human senses to those of animals to show how narrow and limited we are. How despite occupying the same planet with so many remarkable creatures, we make humans the measure of all things, and consider other species as "others." We normalize the planet for ourselves--and look at dogs, dolphins, crows, osprey as "weirdos."

But let me switch to the human realm and Matthew Green's "Shadowlands: A Journey Through Britain's Lost Cities and Vanished Villages," pictured above.

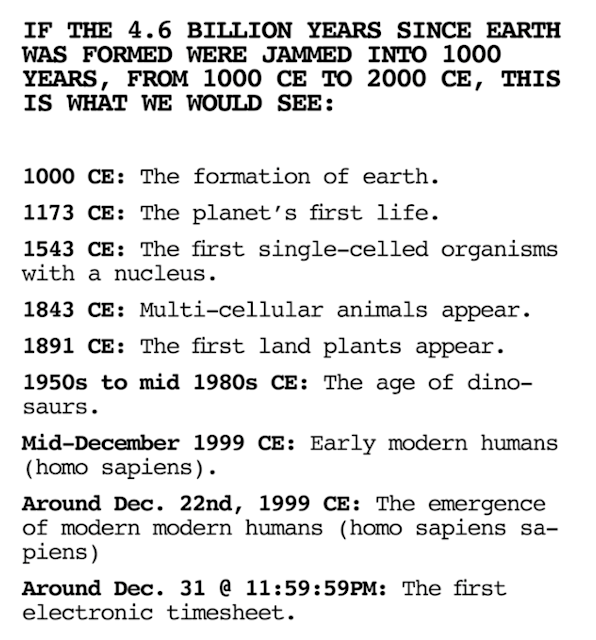

So much of our "breaking news," "living-for-the-next-quarter" culture is sullied by "in-the-moment-ness," we forget that what passes for our planet is been changing constantly for the roughly 4.6 billion years since the Big Bang.

Even since Homo Sapiens arrived on the scene, about 200,000 years ago, we've been changing course like a butterfly in a cyclone. It's easy to walk down the street and see yet another new chain store and think, "Just two-years ago, there was a really good diner there. It had been there forever." Except to modern human sensibilities, forever is about five years.

In reality, the way we measure time and the way our universe measures time are as different as a mensch and donald trump. They simply don't align.

If you think about how the Ancients charted the stars or how they knew where giant pods of whales would be when, it's because they studied these things for hundreds of years--each generation adding to the details and knowledge of the generations that came before. Maps weren't digitized, they were prized and passed-on as received (literally) knowledge.

If you ever wondered how our forerunners spread out from Africa all over the globe--how they got to Siberia or East Asia for instance, it seems nearly impossible with our modern concept of time. But if you understand that to get to China from the Land of Lucy, humans only had to travel a mile a year for 9,000 years, well, that's a relative snap.

Things are worse in Amerika than they are in most everywhere else in the world, because we Americans think we invented the continent. We here have nothing, in an Asian, European, African sense of the word, old.

At least that's the way we see it.

We New Yorkers think of pre-war buildings as old--when they're about 100 years of age. We don't know of Clovis points found in Clovis, New Mexico about 90 years ago. They date from approximately 20,000 BC to 11,000 BC. Yet the town of Clovis, NM, population 39,000, celebrated its 'centennial' in 2009. There are a million instances like that--from the shell mounds in America's southeast to Ahokia in the midwest, to the adobe cities in the southwest. And no one knows for sure, when, or how long the Kelp Highway, brought people from Asia to the Americas.

My point is simple.

We think of time almost cataclysmically. That it's running out. That we are millenarians and are nearing the rapture or the end times, or Elizabeth Kolbert's (another Pulitzer-winner's) Sixth Extinction.

And we may be.

What do I know? I grew up with mis-matched socks in Yonkers, New York and I'm a self-employed copywriter.

However, if you read Shadowlands, any book about "long history," you'll see that the earth itself is not a permanent structure. Cliffs fall into the sea. Rivers change course. Fertile land becomes desert. And once great cities sink into the ground and disappear. Change is what is normal. Permanent is as fantastical as fire-breathing dragons, unicorns and WPP hiring someone over 35.

Of course, as humans, we want permanent. We want our IRAs, and our mortgages paid, and college funds for our grandchildren. We want to believe that we have some control over the future and that we can stop the ever-moving, ever-destroying hands of time.

I suppose a lot of the world's current descent into authoritarianism is because so many people see things changing in ways not to their liking as if, we, humans have something to say about that.

If I ever again had to toil within the pre-fab walls of a razor-thin-margined-holding-company agency, I'd get in every morning at 8AM. I'm a believer in going into the office. I'd settle myself in a conference room and I hold court on the idea of long-history--as it applies to our species, and more specifically as it applies to our industry.

I'd talk about how the most successful marketing campaigns in human history, those from nations like the United Kingdom, the United States, most world religions and major brands like Nike, Apple, Fed Ex, the Economist and maybe one or two others, don't do campaigns that last two years, or five or even more a decade. The most successful marketing campaigns last for centuries. I'd guess, and I could be wrong here, that campaigns don't start etching into human consciousness until they last at least five years--after two years, they're not even launched.

We ought to think about things that improve with time, grow with time, last through time. Bernbach called them "simple, timeless human truths."

Not just keeping up with the times.

No comments:

Post a Comment